I want to suggest today that globalization as a process has reached a new condition, akin to that reached by modernization in the 1950s.

In using the term "late globalization," I am referring to Ernst Mandel's concept of late capitalism, the point when capitalism was everywhere, saturating the world. With the spread of the Internet and mobile telecommunicational devices, the disconnected world of the past is long gone, rapidly becoming unfamiliar to us. Soon, the disconnected world will become unintelligible, its artifacts and ways of life lost to generations that will have no experience of it. If, in 1999, TJ Clark could write of "modernism is our antiquity…" then today we must add postmodernism to our antiquity as well.

The global credit crisis of 2007 and 2008 marks a further turning point in globalization. With the production of mortgage-backed securities, it became possible to easily and abstractly trade in real estate, formerly the slowest, heaviest, and most immobile form of investment. Fueled by delirious amounts of excess capital accumulated during the operations of globalization, the real estate boom and bust marked the point of globalization's oversaturation.

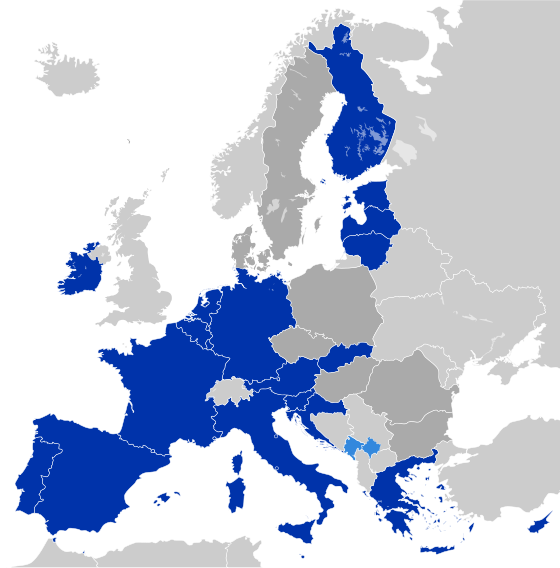

Since then, the removal of barriers that has marked globalization has slowed and even reversed in some cases. The Eurozone is under stress, even in danger of collapse. As the price of labor in China rises but falls in the United States, the US's industrial production is rising, Chinese imports to the US are declining and China is finding its domestic market more and more important. But we are also seeing a resurgence in nationalist movements and a rise in state capitalism. This is not to say that the removal of some barriers will not continue, but that we are now in a different dynamic in which continued globalization should not be assumed.

Still, with the spread of global trade and telecommunications it is impossible to return to the previous era. The idea of jetting off for a weekend abroad is no longer the province of the rich and famous. Even the idea of the "jet set", as a distinct group, has faded (excepting of course the private jet set… about which more later). Constant travel and continuous cross-border communication has become a fact of everyday life for individuals throughout the world. Tourism is now a familiar practice rather than an exotic one, taking the same forms throughout the world, reducing formerly distinctive places across the globe—the Rambla, the Île de France, Hollywood Boulevard, Venice's San Marco—to the same condition, occupied by the same people. The Bilbao-Effect is also consigned to history, becoming less and less important, a product of a globalizing world, not one that has globalized.

At the Netlab, Leigha Dennis, Cloud Communications Officer at GSAPP and I will be working together with Tim Ventimiglia, Senior Associate of Ralph Appelbaum Associates to explore this condition of oversaturation in depth, to understand how it manifests itself in economic, social, and cultural terms. Our goal, which we have begun to explore in this research blog, is to investigate the changing landscape of travel at a crucial juncture in world history.