This is the second in my (weekly?) series of posts on recent reading. I’m finding it lets me reflect on what I’ve studied during that time and that, in itself, is useful, but it also gives back to you, my readers, so I’ll keep doing it as an experiment for a month and maybe longer. I’ve read two books in the last week. The first is Eric Berger’s Liftoff! Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days that Launched SpaceX and the second is 2034: A Novel Of The Next World War by Admiral James Stavridis and Marine Corps veteran Elliot Ackerman which I stumbled into via the pages of Wired Magazine. I’m going to go into these in considerable depth—with a rant about architectural education along the way—so I plan to skip links for this week and aggregate them together next week.

Berger’s Liftoff! is an engrossing account of how radical the now familiar SpaceX project was, how close SpaceX was to failure even after the fourth launch of the Falcon 1 rocket finally reached orbit, and the emotional toll of working at SpaceX. Space exploration is a critical human endeavor and yet, NASA’s annual budget is the same as that of Netflix and nobody has done more to make it more accessible than SpaceX.

Throughout the book, Berger focuses on the differences between SpaceX and old aerospace companies like Boeing or Lockheed Martin (now working together as the United Launch Alliance). I’ve previously written quite a bit on how dangerous complexity is to society because the construction of parasitic entities such as human resources managers, UX architects, SCRUM masters, and all the other bullshit jobs that consume massive amounts of resources and energy. SpaceX cut through all that. For example, the lead avionics engineer Bulent Altan describes how whereas in most companies on the first day of the job it would have been an accomplishment to establish an account with the IT department, at SpaceX he designed a printed circuit board and sent it to manufacturing. This kind of instance is told time and again throughout the book. It’s instructive that Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, founded earlier than SpaceX, still hasn’t been to orbit even as SpaceX has successfully launched the Falcon 1, Falcon 9, Falcon 9 Heavy, sent a crewed capsule to the ISS twice, fully integrated booster recovery into its launches, and is now working on the fully reusable Starship spacecraft. Watching Starship is instructive; whereas proponents of outdated technology like NASA’s Space Launch System have been laughing at the explosions at the ends of the first few Starship flights, SpaceX is churning out one ship after the other, performing iterative tests to refine the design as well as the assembly line. Key to all this has been SpaceX’s ability to attract talented individuals who dedicate themselves to the mission of making space less expensive. At one point, University of Michigan professor Thomas Zurbuchen made a list of the top ten students he taught during the last decade and noted that fully half were at SpaceX. Musk called him and asked who the other five were so he could recruit them. Eighty hour work weeks at SpaceX were normal and the emotional toll on everyone—including Musk—was extreme. But for the individuals involved, the toll was worthwhile to advance the cause. This is a fascinating book and, although Musk is a controversial figure, it puts his achievements and those of the many other individuals involved in perspective. It’s a quick read and I highly recommend it.

The never-ending work and emotional toll described in Liftoff! isn’t foreign to people who studied, practiced, or taught architecture. But there are some critical differences. First, there is rarely any goal to the sacrifices demanded from young architects except for the students’ desire toward running a trendy boutique studio or teaching at a prestigious school. Although I only taught at schools that proclaimed themselves to be innovative and disruptors, goals were never clearly articulated or followed through with. Instead, it was an endless amount of busy work and attempts by faculty to second guess what the heads of school wanted and how to fit their agendas for promotion. Architecture schools are driven by three forces: patriarchy at its worst, a misguided idea of fashion, and university bureaucracy. There is no greater dream, there is no mission, no expectation of real research, only the need to compete and prove oneself in the patriarchy. Rewards do not come to those who accomplish things, but to those who play the game and get lucky. The head of one graduate program once said of young faculty, you use these people up and then they go away. This is the attitude of many administrators at the top schools. They survived, they made it and everyone else has to go through the process of self-exploitation just like them and, like minnows, most will end their journeys before they get very far. Architecture school is insanely patriarchal and I have little illusion about recent efforts to wash that away. Schools inevitably rely on models of the head of school as a Christ-like savior and these administrators see themselves in precisely that role. But usually, heads of architecture programs have, in turn, to answer to university presidents and provosts who have no idea how to judge anything so rather than innovating, the typical response is to make sure school output is the flavor of the day and obscure fashions—like the blob or tactical urbanism or creating startups in schools—take priority. In one program, there was an effort to ask Nobel Prize winners on film about what they like about cities, as if such a thing was worthy of research at a graduate level (or the time of a Nobel laureate), and then a few months later, the whole project was thrown in the toilet. Months of work with nothing to show for it, although in retrospect, it would be worse for all involved if the project had actually been finished and names were associated with it. Since most schools still have tenure, the requirement to publish or perish means that faculty in top schools have to publish at least two books to get tenure, which means that those books will be filler. Busy-work instead of actual research. In turn, accreditation imposes yet another layer of complexity, requiring the development of a shadow curriculum that would then be shown to the accreditors to mask what is actually going on in the school. If architecture students historically had worked extreme hours as part of their initiation into this exploitative system, the importance of admitting and keeping ever-increasing numbers of students to fund more staff to administer all this complexity means that faculty find students who not only wouldn’t put in crazy hours in the studio, but expected top grades with barely work at all, a wild swing of the pendulum in just a few years. “Your project is so amazing,” I remember one faculty member saying at the once formidable midterm studio crits as I stared at the drawings and sought to understand how the student had put more than an afternoon of work into their design and presentation. So a massive disjuncture has occurred in architecture: schools have no direction but still expect faculty to break themselves. Most of the smartest people I know have left the profession. Always have an escape plan, Hal Foster once told me. He was right and my twenty-year side venture in real estate development funded my escape into autonomy.

Now architecture schools are not aerospace companies and I firmly believe that architecture is not just a matter of investigating new materials and the latest software but rather also involves coming to an understanding of how we relate to the spatial world around us, and that’s been my project throughout my academic and architectural career. We can’t just set a destination, but schools could find ways to get the best faculty together and then get out of their way. It’s entirely possible to build a better model for architecture school, but like SpaceX, it’s going to have to be a radical break, one free of fashion, university administration, and accreditation. It’s unclear if such a possibility is out there. Until then, the best students will continue to avoid architecture for more interesting terrain—such as the New Space movement—faculty will continue to lead entirely unsustainable, purposeless lives, and architecture schools will continue their slow slide into obscurity.

On to 2034: A Novel of the Next World War. You can read a good portion of the book in the February Wired. To call the book a novel is probably a bit of a misnomer, it’s an exercise in scenario planning done as a novel and reads as such. The characters are barely developed, but that hardly matters, the book’s purpose is clear. In Wired, Stavridis argues that Cold War works of fiction about annihilation, such as the Day After and the Third World War, may have helped stave off actual war. True enough, that is arguably the purpose of post-WW2 war gaming in the first place and he has hopes that this book might do the same. A few premises animate the book: that globalization is well and truly dead in favor of ever-heightened nationalism, that China develops new levels of stealth technology as well as the ability to hack and control American computer systems at a distance, and also that India becomes much more developed and powerful under Modi.

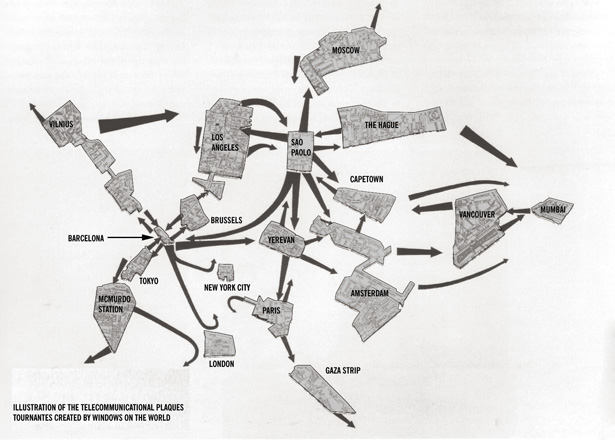

I found 2034 an enjoyable and provocative read although I found the new technologies to be too magical. For example, in the opening pages, one of the critical flash-points involves an American F-35 fighter outfitted with new electronic stealth technology being remotely captured by the Iranians with the help of Chinese technology. If there is a prospect for a technology for remotely hacking into and controlling a computer system that has no remote login capabilities and no connection to outside networks, I’d love to hear how that might work. This remote control capability is a big part of the book and it’s a flaw for me. There are easier ways to imagine a first strike by a technologically advanced enemy: targeted electromagnetic pulses to knock out facilities or entire regions, attacks on satellites such as the United States GPS system, or hacking of the banking or critical infrastructure systems. And there are more disruptive first strike capabilities possible too; it’s no accident that China and Russia are investing substantial sums on general artificial intelligence research and exploring SETI. First contact with a different, likely superior, intelligence—be it computational or extraterrestrial—could be a phenomenal game changer, leaving the West in the position of the Aztecs facing the Spaniards. This was, by far, the most interesting aspect of Liu Cixin’s Three Body Problem, although unfortunately that premise was left behind in subsequent novels of the trilogy, which is certainly a more cautious move if an author lives in China. Or perhaps the Chinese might find a way to produce a new generation of warfighting machines in much, much larger numbers than the West can muster. There are only 195 F-22 Raptors and 375 F-35 Lightning IIs in service in the US military. While there are only 50 Chengdu J-20’s, the Chinese fifth generation fighter, in service, there were over 15,000 P-51 Mustangs in service during World War II. One way warfighting machines could be produced in vast numbers would be if they were autonomous drones rather than human-piloted fighters and attack aircraft. Such drones could attack aircraft carriers en masse, overwhelming defenses and taking them out. That could change the situation for a country like Iran or North Korea rather rapidly, but luckily at present neither seems capable of developing such technology although China certainly does seem capable of that. On a geopolitical front, Russia’s motivations in the book are muddled and India’s rise to superpower status seems improbable. All this makes it sound like I didn’t enjoy the book, but I did. It’s a quick read and provocative. The authors argue that over-reliance on technology is risky, that technology can be blocked, and in an interview at NPR, Stavridis argues for primitivization in modern warfighting, e.g. having a plan B in case our technological measures are defeated, such as navigating with sextants and charts. We need more fiction like that. Even a reader’s disagreement with aspects of the book is productive as it provokes thought. The scenario plan that I produced with the Netlab addressing Hong Kong and China’s future for MoMA may seem wildly wrong right now but may yet prove useful for thinking through what could happen in those places in the future as China’s population collapses. Both Liftoff! and 2034 are quick, worthwhile reads, I recommend them.