I’ve been working with art and Artificial Intelligence image generators recently. Untalented artists are scared of AI image generators since they are tools for making bad art, which is all that is being promoted in the press. All of the image generators—save perhaps for Dall-E 2—are tuned to produce such work in order to generate revenue. Ed Keller calls this “the black light black velvet painting of our time.” AI Art is likely to destroy ArtStation and Deviant Art. But we have a jobs crisis and need people to work in more important positions like food service. Who can argue that this re-allocation of human labor is bad?

Virtually all the work being done with this—even work that is lauded as exemplary—is bad. A few friends do interesting work. I will let them publicize it, although it’s safe to say Ed is interrogating these generators as a medium, pushing their boundaries in ways that are interesting to me. A recent article on the topic in the Architects’ Newspaper highlighted only bad work. Patrick Schumacher has convened a symposium on “futuristic” work indistinguishable from his own, which means that it is midbrow and pedestrian. Archdaily published a piece that gives the impression that AI interior designs are the stuff of nightmares. I could waste my time and yours coming up with more links to bad work.

This should not surprise anyone. Almost everything is bad because intelligent thought in architecture is now nearly extinct.

Making interesting work with AI image generators requires work. It doesn’t take as much time as it might to create a painting by hand, but an AI painting might take hours, a day, or more. One needs a plan and a mind for experimentation. AI art generators are incapable of originality. Neither are almost all artists working today. That should not stop anyone as until the modern era, originality was not valued. In the Renaissance, “genius” did not mean making an unprecedented work, rather it meant the ability to shape something pleasing out of existing sources.

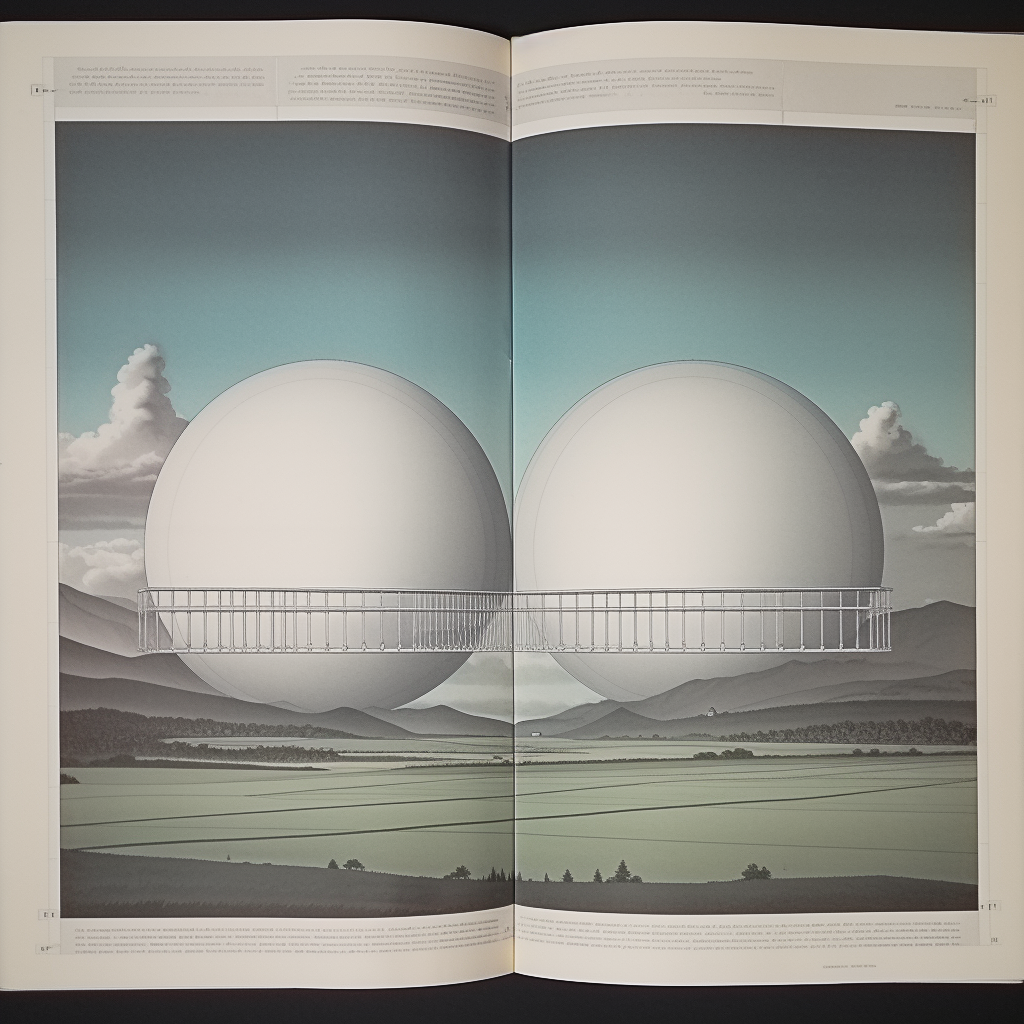

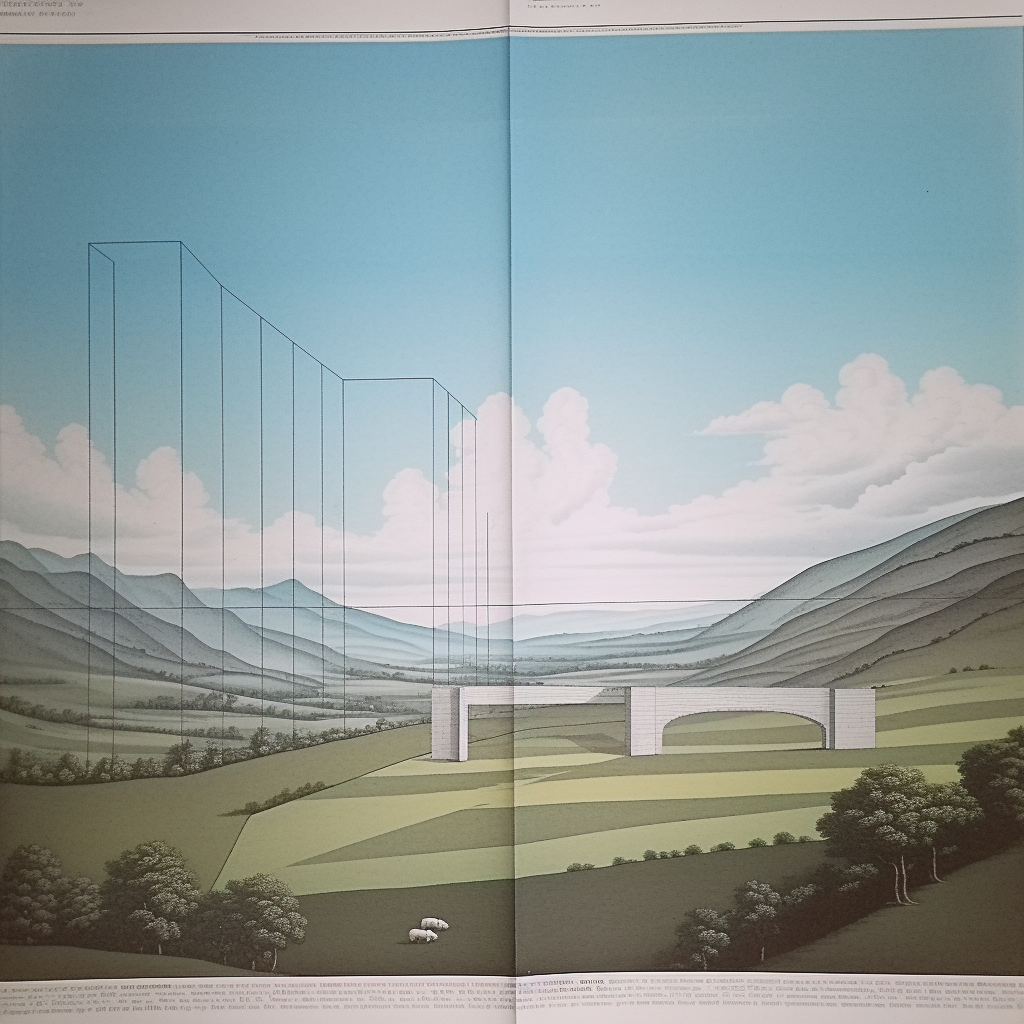

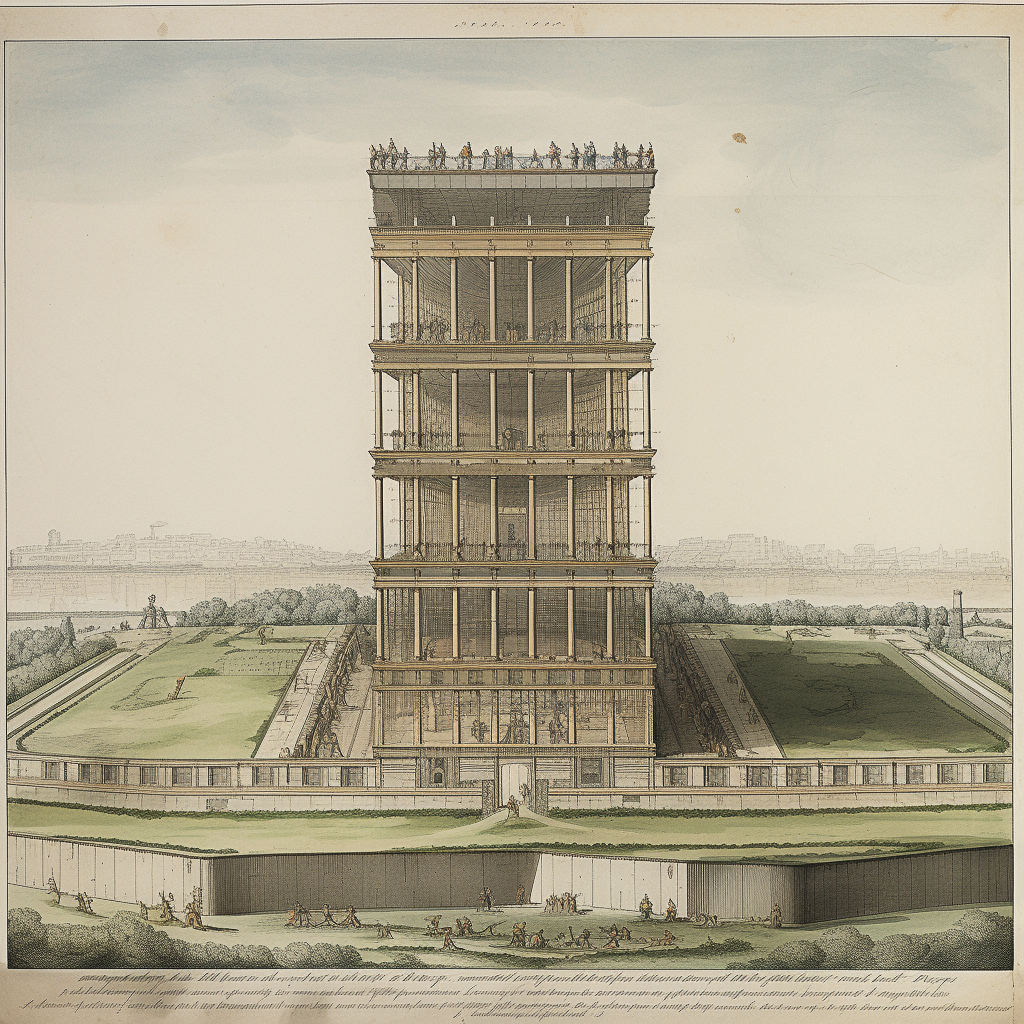

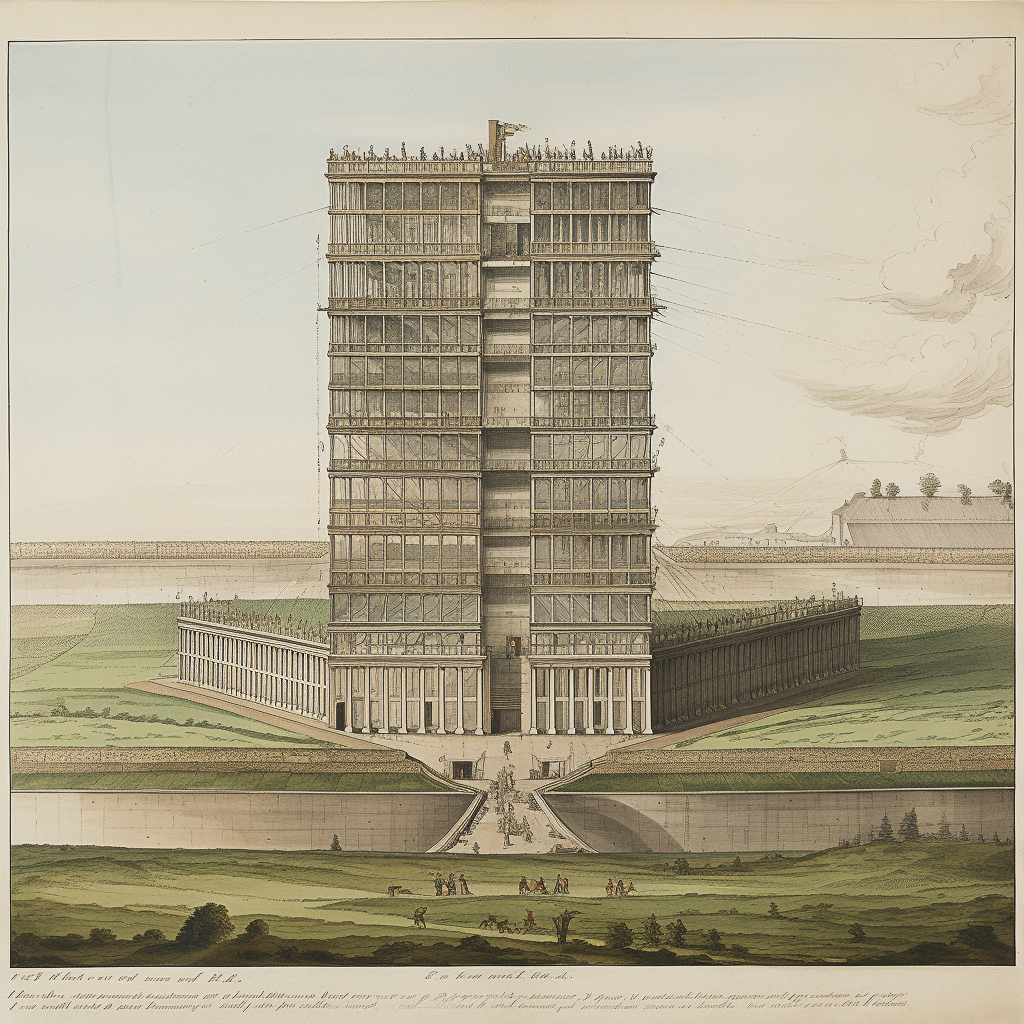

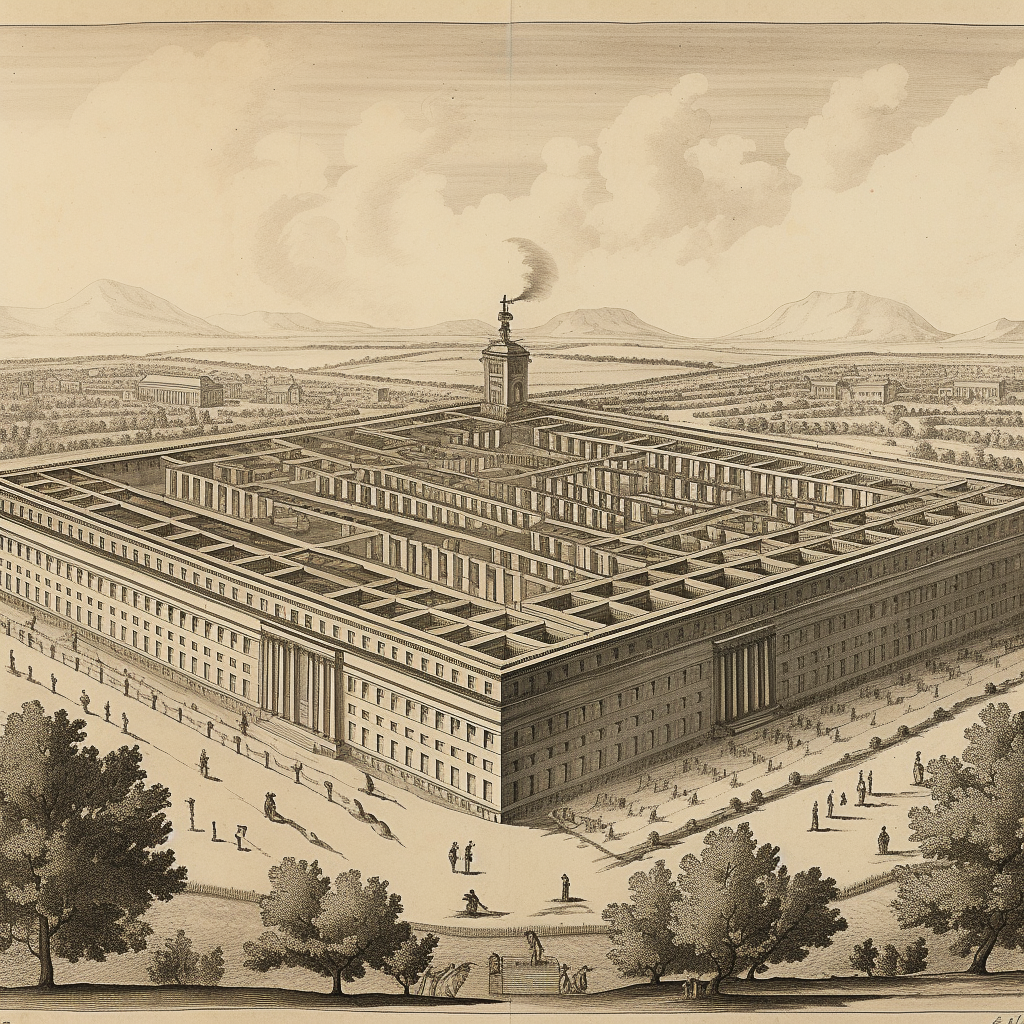

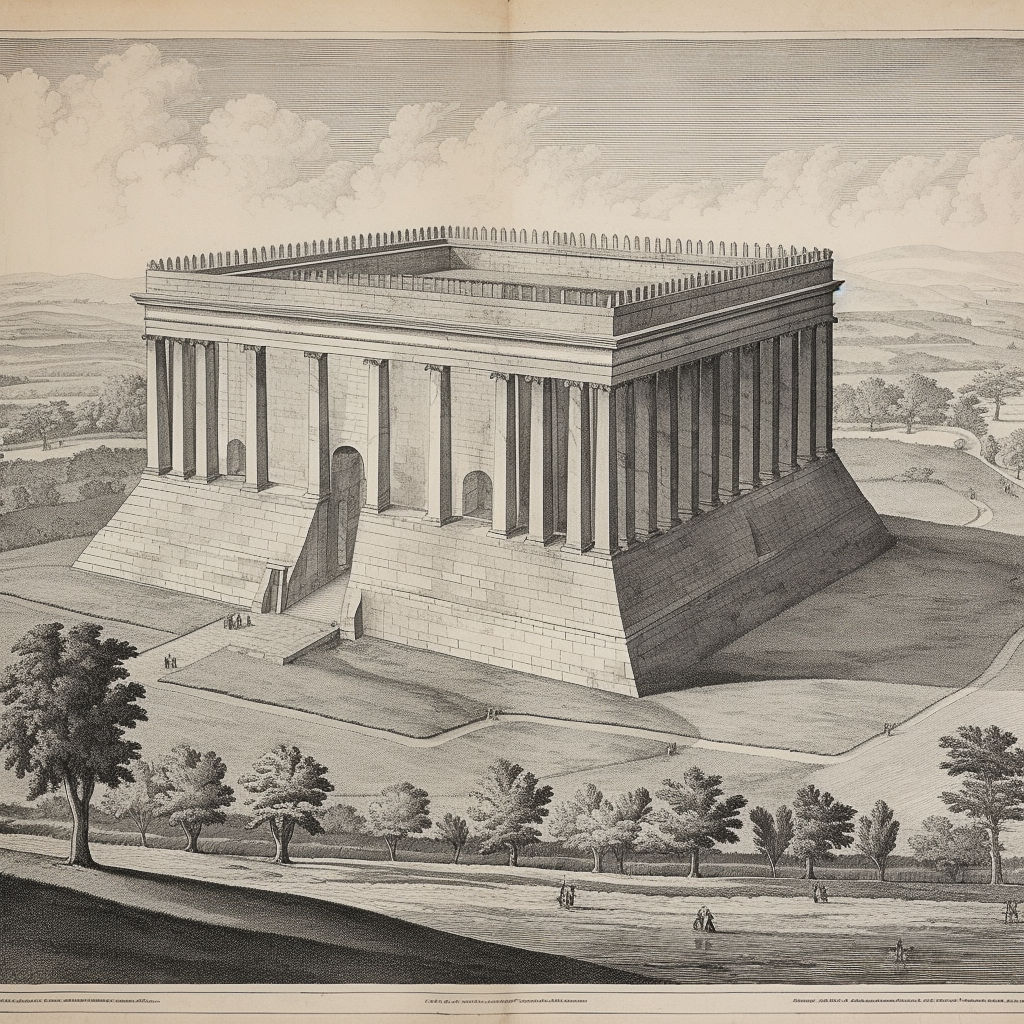

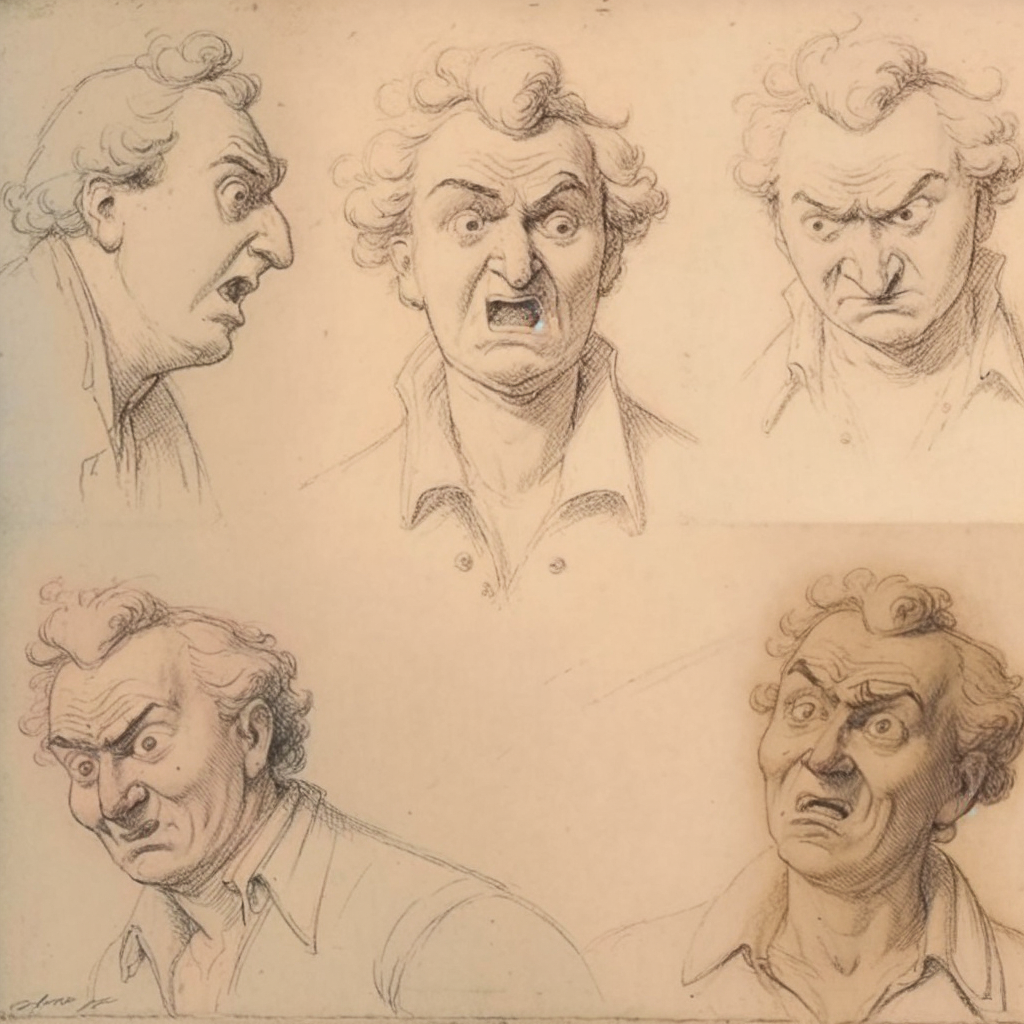

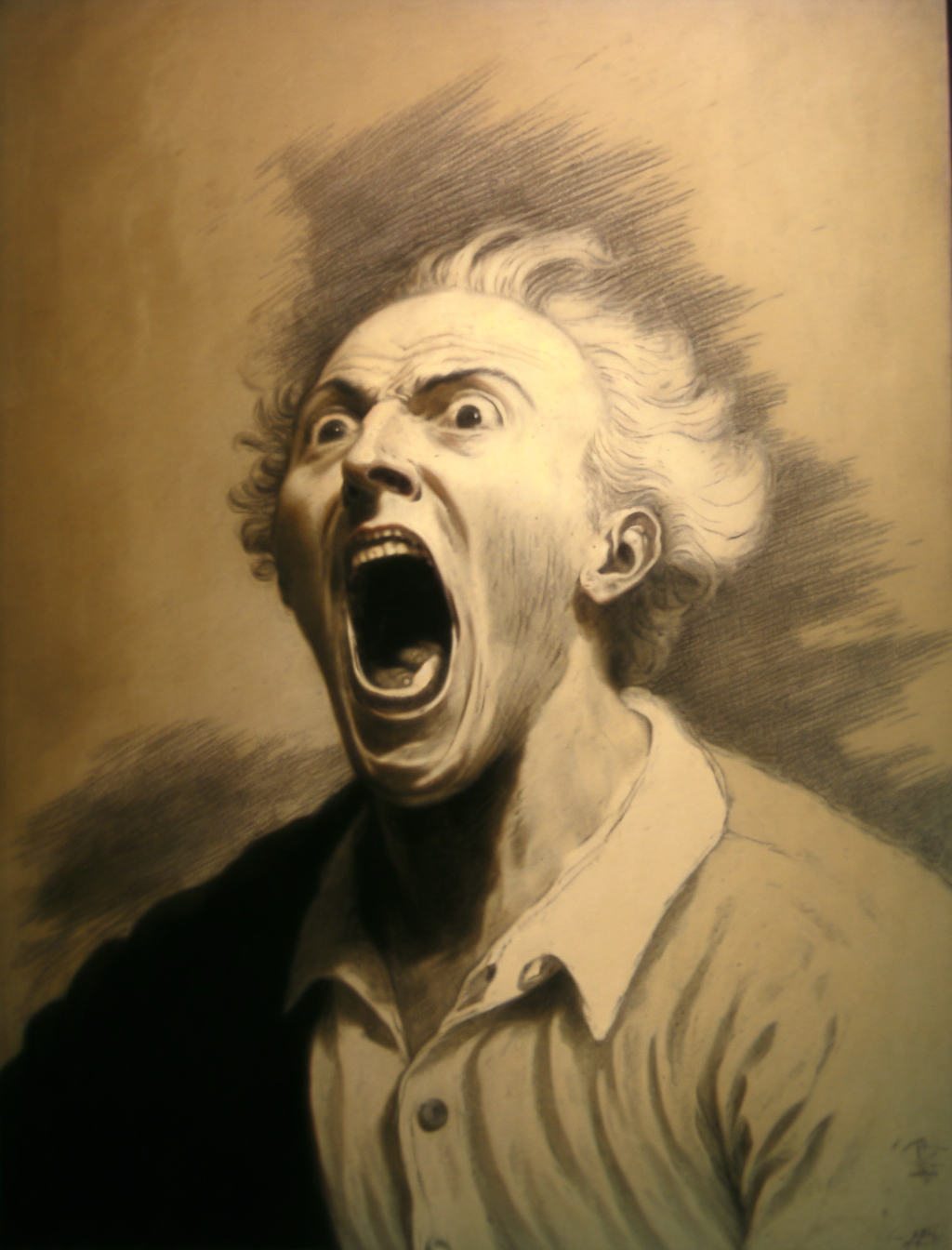

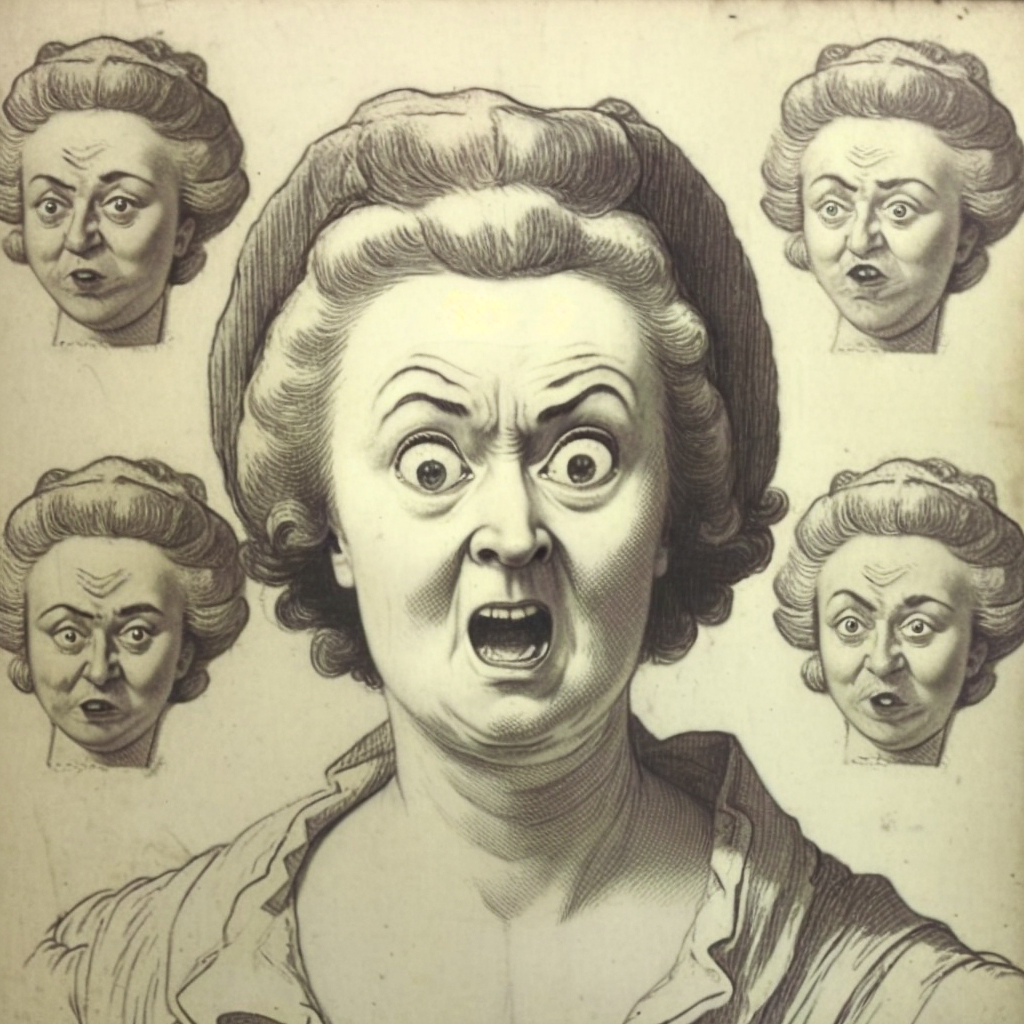

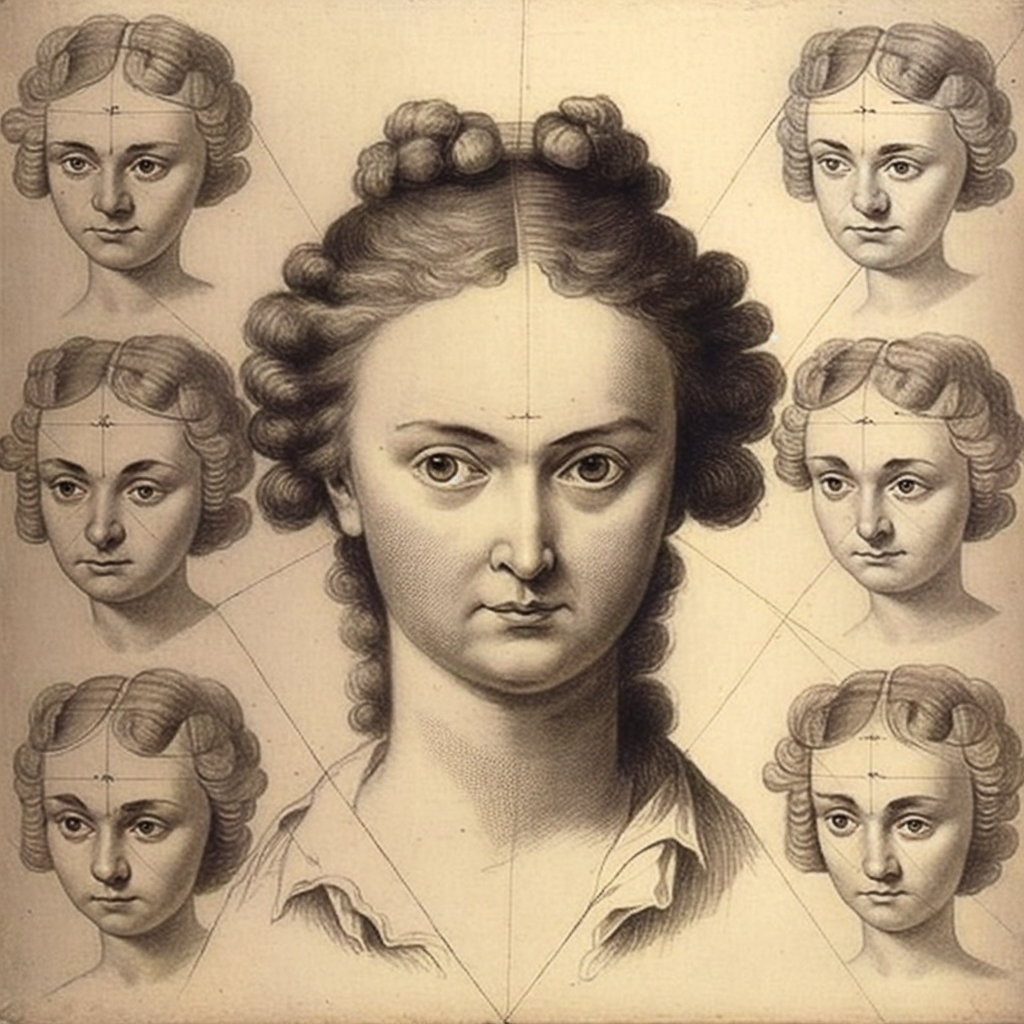

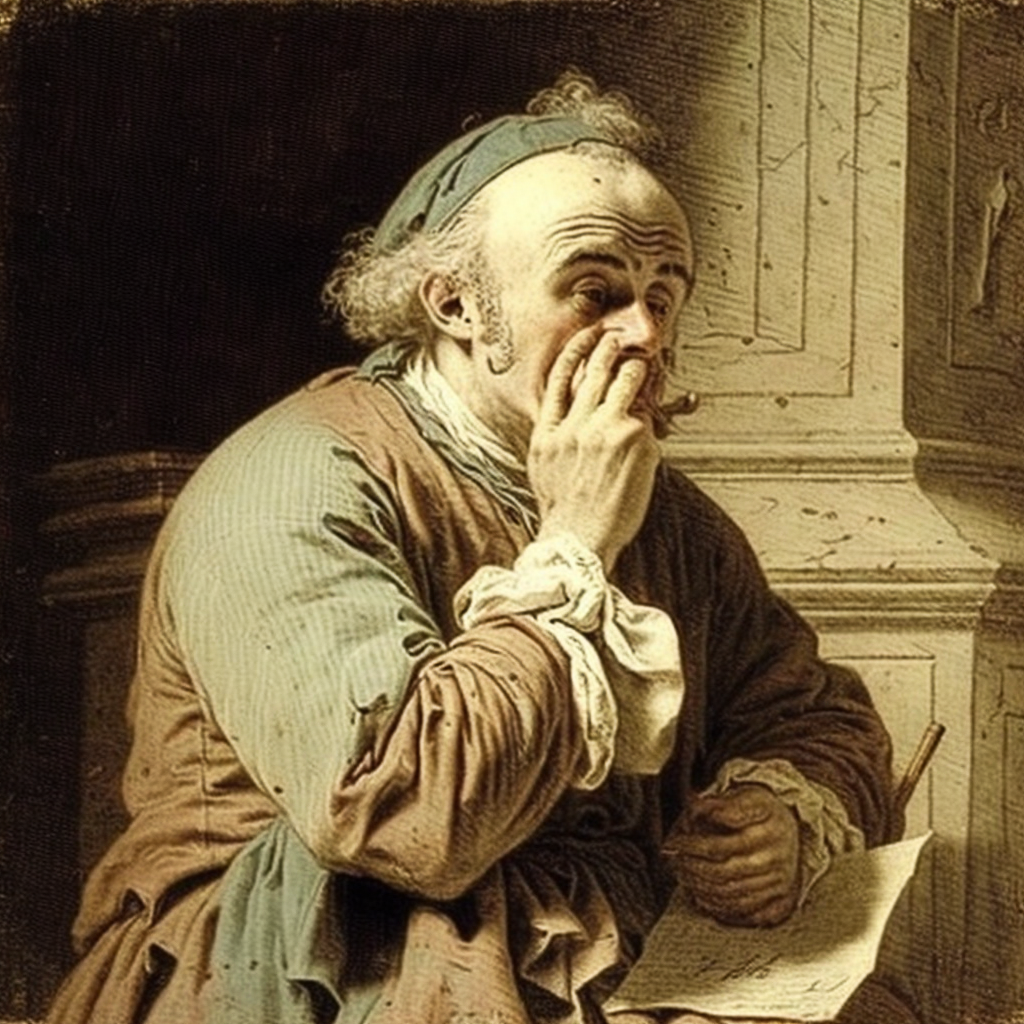

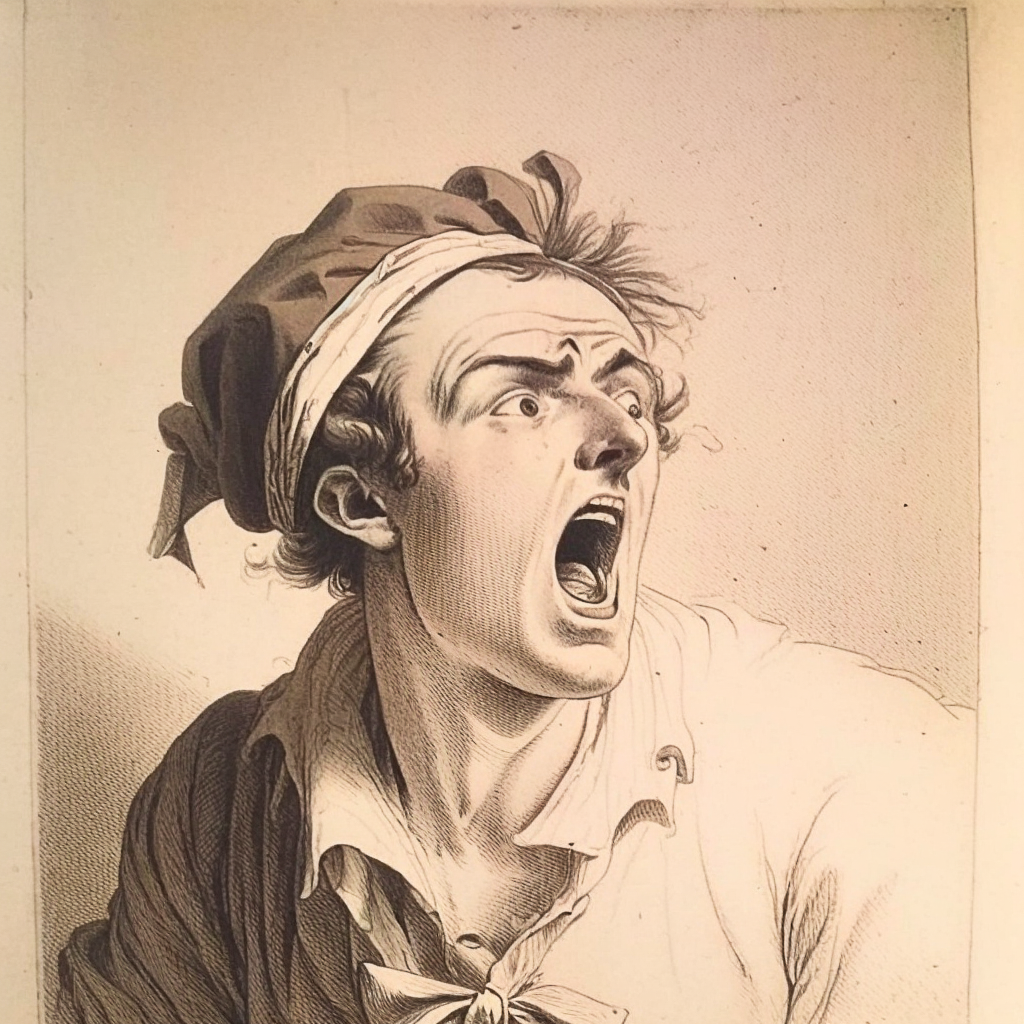

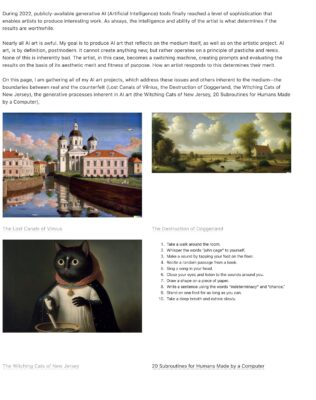

AI image generators create forgeries. One appropriate response, then, is to use them to create explicit forgeries. I undertook this as a project starting this summer with the Lost Canals of Vilnius, the Drowning of Doggerland, and the Witching Cats of New Jersey.

Any good forgery begins a kernel of truth. Basing texts and images on existing sources, I created alternate histories. I used a feedback effect: provocative works created by the image generators inspired my alternate histories and ideas from the alternate histories guided the prompts for image generators. Most of the work was done with Dall-E 2 since it alone is tuned to produces semi-convincing paintings and photographs.

I unintentionally duped some readers. But AI art and text generators are already being used to deceive people for political purposes, to satisfy high school and college requirements, and for work purposes. Convincing people has never been easier. This project was intended to foreground this. I intend to write an essay for this site on the topic, but this one came out first. I am in Vilnius, Lithuania which is not boring like New York City. Visiting here often jars me out of complacency, spurs new ideas, and forces action.

A related route is to use AI art in a surrealist sense. This does not mean prompts for paintings in the style of Salvador Dali. That is kitsch and awful. Rather, this is a way of accessing what Jung called the collective unconscious to produce visual automatic writing: Pinot-Gallizio’s “Industrial Painting” updated for our day. In a sense, the “Witching Cats” project came out of a prompt for a black and white cat that came out gruesomely misshaped, became an amusing diversion for Instagram, led me to read about photography and the occult in the nineteenth century, and that, in turn led to the essay and project. Otherwise, I have not released this work. I may or may not.

Two days ago (30 November 2022), OpenAI released a freely-accessible interface to ChatGPT, a language model capable of conversation in the format of a dialogue. Although it is possible to trip it up, it is also remarkable how effective it is at generating content, even content that can be quite lengthy and complex in nature. I began by trying to produce critical essays.

In all of these, my prompt will come first.

>In 1,500 words, compare “Modernist Painting” by Clement Greenberg and “Art and Objecthood” by Michael Fried.

Modernist Painting by Clement Greenberg and Art and Objecthood by Michael Fried are two important essays that address the question of what constitutes modernist painting. While both essays address this question, they take very different approaches and come to somewhat different conclusions.

In Modernist Painting, Greenberg argues that the defining characteristic of modernist painting is its emphasis on the flatness of the canvas. He argues that the history of painting is one of the progressive flattening of the picture plane, and that modernist painting represents the culmination of this process. According to Greenberg, the flatness of the canvas allows the painter to focus on the formal elements of the painting, such as line, color, and composition, and to create a more intense and immediate visual experience for the viewer.

In contrast, Art and Objecthood takes a more philosophical approach to the question of modernist painting. Fried argues that the defining characteristic of modernist painting is its refusal to be reduced to a mere object in the world. He argues that modernist painting is defined by its ability to transcend the merely physical and to create a “presence” that is distinct from the physical object of the painting itself. According to Fried, this “presence” is what allows modernist painting to truly engage the viewer and to create a meaningful artistic experience.

One key difference between the two essays is their focus. While Greenberg is primarily concerned with the formal qualities of modernist painting, Fried is more interested in its philosophical and artistic implications. This difference is reflected in their respective conclusions. While Greenberg ultimately argues that the flatness of the canvas is the defining characteristic of modernist painting, Fried argues that it is the ability of the painting to create a “presence” that sets it apart from other forms of art.

Another important difference between the two essays is their treatment of the viewer. For Greenberg, the viewer is an essential part of the modernist painting experience. He argues that the flatness of the canvas allows the viewer to engage more directly with the formal elements of the painting, and that this creates a more intense and immediate visual experience. In contrast, Fried is less concerned with the viewer’s experience of the painting and more interested in the painting’s ability to create a “presence” that transcends its physical form.

Overall, Modernist Painting by Clement Greenberg and Art and Objecthood by Michael Fried are two important essays that address the question of what constitutes modernist painting. While both essays take different approaches and come to different conclusions, they both provide valuable insights into the nature of modernist painting and its place in the history of art.

>Write a 2,000 word analysis of the song “Rid of Me” by PJ Harvey

PJ Harvey’s 1992 hit “Rid of Me” is a raw and emotional exploration of the pain and anger that can arise in a toxic relationship. Through the use of aggressive and confrontational lyrics, coupled with her powerful and haunting vocals, Harvey exposes the desperation and helplessness that can arise when trying to leave a harmful relationship.

The song opens with a haunting and intense instrumental introduction, featuring distorted guitar riffs and driving drums that set the tone for the rest of the track. This instrumental introduction immediately establishes the song’s aggressive and confrontational atmosphere, setting the stage for the confrontational and emotional lyrics that follow.

The first verse begins with Harvey’s powerful and haunting vocals, as she sings: “I want you gone / But I want you still.” This opening line perfectly encapsulates the confusion and conflicting emotions that can arise when trying to leave a toxic relationship. On the one hand, the narrator wants to rid herself of her partner, but on the other hand, she still desires their presence and connection.

The chorus, which follows the first verse, features the repeated line: “Rid of me / Rid of me.” This chorus serves as a cry for help and a desire to be free from the suffocating and harmful relationship. The repetition of the line, coupled with Harvey’s powerful and emotive vocals, emphasizes the narrator’s desperation and longing for freedom.

The second verse continues with the narrator’s emotional turmoil, as she sings: “I’m an animal / I’m a dog / I’m a death / I’m a thief.” These lyrics paint a vivid and disturbing picture of the narrator’s state of mind, as she feels trapped and degraded in her relationship. The use of animalistic imagery also highlights the loss of humanity and dignity that can occur in a toxic relationship.

The bridge of the song features the line: “I’m a mess / I’m a wreck / I’m a fault / I’m a scar.” These lyrics further emphasize the narrator’s feelings of inadequacy and worthlessness in the relationship. She sees herself as a burden and a source of pain for her partner, and longs for the release of being free from the relationship.

The final verse of the song features the line: “I’m not a child / I’m not a pet / I’m not a toy / I’m not a doll.” This line serves as a powerful declaration of the narrator’s autonomy and independence. She rejects the idea of being treated as a possession or object, and asserts her own worth and dignity.

The song’s instrumental outro features a repetitive guitar riff that gradually builds in intensity, culminating in a ferocious and powerful finale. This instrumental finale perfectly captures the narrator’s emotional release and liberation as she breaks free from the toxic relationship.

In conclusion, “Rid of Me” is a raw and emotional exploration of the pain and anger that can arise in a toxic relationship. Through the use of confrontational and powerful lyrics, coupled with Harvey’s haunting and emotive vocals, the song exposes the desperation and helplessness that can arise when trying to leave a harmful relationship. The song’s intense and driving instrumentals perfectly capture the narrator’s emotional turmoil and eventual release, making it a powerful and impactful anthem for anyone who has experienced the pain of a toxic relationship.

Unfortunately, ChatGPT can make mistakes and there are mistakes in that essay. Later, I asked it to write about the relationship between Vytautas Landsbergis and George Maciunas and it stated that while they are both Lithuanians interested in Fluxus and music, they had no direct relationship, which is untrue. ChatGPT receives a failing grade for not meeting the required word count, although adding those phrases produces longer analyses.

Still, the above essays are better than what 95% of graduate students are capable of doing in an afternoon or, usually, a weekend. This should not be surprising as, while ChatGPT is incapable of original thought, so are 95% of graduate students and, indeed, 95% of faculty.

When I did my dissertation at Cornell, a dissertation was defined as a “contribution to knowledge” but the vast majority of such work in the humanities is formulaic: find an obscure topic related to an important topic (an unknown modern architect in Brazil in the 1960s who made middling buildings but met Lina Bo Bardi at a restaurant for dinner once or a failed, uninteresting project by someone who saw Le Corbusier speak) represented in an archive, go to said archive, find some obscure fact of no importance and blather on about how important said find is, add a conclusion in which Foucault is invoked to make the work “political,” and submit as a dissertation. Or at least that was a “good,” Ivy-level dissertation in the 2000s. Today one would have to add some random verbiage about marginalized communities, identity, and oppression to indicate that one is more “political.” Such work is not intended to be original, but rather to indicate that one has been properly disciplined in graduate school and is now capable of independently programming other students to also produce work of no importance whatsoever. If it is true we live in a simulation, most of these people are NPCs. Original thought is almost non-existent.

If an AI can equal or better such work today, albeit only in short pieces, imagine it in a few years.

ChatGPT can also be used to create instruction-based art. A series of these follow.

>produce a textual score by John Cage

0’00”: Silence

0’01”: A single piano note is struck

0’02”: Silence

0’03”: A second piano note is struck

0’04”: Silence

0’05”: A third piano note is struck

0’06”: Silence

0’07”: A fourth piano note is struck

0’08”: Silence

0’09”: A fifth piano note is struck

0’10”: Silence

0’11”: A sixth piano note is struck

0’12”: Silence

0’13”: A seventh piano note is struck

0’14”: Silence

0’15”: An eighth piano note is struck

0’16”: Silence

0’17”: A ninth piano note is struck

0’18”: Silence

0’19”: A tenth piano note is struck

0’20”: Silence

0’21”: An eleventh piano note is struck

0’22”: Silence

0’23”: A twelfth piano note is struck

0’24”: Silence

0’25”: A thirteenth piano note is struck

0’26”: Silence

0’27”: A fourteenth piano note is struck

0’28”: Silence

0’29”: A fifteenth piano note is struck

0’30”: Silence

0’31”: A sixteenth piano note is struck

0’32”: Silence

0’33”: A seventeenth piano note is struck

0’34”: Silence

0’35”: An eighteenth piano note is struck

0’36”: Silence

0’37”: A nineteenth piano note is struck

0’38”: Silence

0’39”: A twentieth piano note is struck

0’40”: Silence

0’41”: A twenty-first piano note is struck

0’42”: Silence

0’43”: A twenty-second piano note is struck

0’44”: Silence

0’45”: A twenty-third piano note is struck

0’46”: Silence

0’47”: A twenty-fourth piano note is struck

0’48”: Silence

0’49”: A twenty-fifth piano note is struck

0’50”: Silence

0’51”: A twenty-sixth piano note is struck

0’52”: Silence

0’53”: A twenty-seventh piano note is struck

0’54”: Silence

0’55”: A twenty-eighth piano note is struck

0’56”: Silence

0’57”: A twenty-ninth piano note is struck

0’58”: Silence

>produce a textual score by John Cage

- Open the piano lid.

- Place a single sheet of paper on the piano keys.

- Using a pencil, randomly draw lines and shapes on the paper, creating a visual score.

- Sit at the piano and interpret the visual score, allowing the lines and shapes to guide the movements of your hands on the keys.

- Explore different sounds and timbres by experimenting with various techniques, such as striking the keys with different parts of your hand or using the pedals.

- Allow the music to emerge naturally and organically, without predetermined melodies or harmonies.

- Continue to improvise and explore the piano’s soundscape for a set duration of time, determined by the performer.

- When the performance is complete, gently remove the sheet of paper from the piano keys and close the lid.

- Reflect on the experience and the unique sounds and melodies that emerged during the performance.

>write the instructions for a new Sol Lewitt pencil wall drawing

- Choose a wall in your space that has a minimum height of 8 feet and a minimum width of 10 feet.

- Measure the dimensions of the wall and divide it into equal horizontal and vertical sections, creating a grid pattern with a minimum of 10 horizontal and 10 vertical lines.

- Using a pencil, randomly select one of the grid squares and draw a line that extends from one edge of the square to the opposite edge, without crossing any other lines or touching the sides of the square.

- Repeat this process for each of the grid squares, creating a series of lines that fill the entire wall.

- Experiment with different line lengths, angles, and directions in order to create a varied and dynamic composition.

- Avoid erasing any lines or making any corrections, and allow the drawing to evolve organically.

- When the drawing is complete, step back and admire the final composition.

- Optional: photograph the drawing and share it with others.

>write the instructions for a new Sol Lewitt pencil wall drawing

- Choose a blank wall in a well-lit area to create your wall drawing.

- Using a ruler and a pencil, draw a horizontal line across the center of the wall.

- Draw a second horizontal line above and below the center line, each spaced at equal intervals.

- Draw a third set of horizontal lines, above and below the second set, at the same intervals.

- Continue adding sets of horizontal lines until the entire wall is covered with a grid of evenly spaced lines.

- Using a different color pencil, randomly draw diagonal lines connecting the horizontal lines.

- Experiment with different patterns and densities of diagonal lines, creating a unique and visually interesting composition.

- Step back and observe the overall composition, adjusting and refining the diagonal lines as needed.

>write an instruction piece in the style of a list by Yoko Ono

Choose an everyday object, such as a paperclip, a pencil, or a piece of string.

Place the object in a simple, unadorned setting, such as on a blank sheet of paper or a plain background.

Using a camera or smartphone, take a photograph of the object in its chosen setting.

Share the photograph on social media, along with a simple and enigmatic caption that invites viewers to interpret the object in their own way.

Consider how the chosen object and its placement in the photograph might evoke emotions, thoughts, or memories in the viewer.

>write an instruction piece in the style of a list by Yoko Ono

Find a quiet, peaceful space where you can be alone and undisturbed.

Close your eyes and take a few deep breaths, allowing your body and mind to relax.

Slowly open your eyes and look around your surroundings, taking in the details and textures of the space.

Imagine yourself floating in a vast, empty void, free from the constraints of time and space.

Allow your mind to drift and explore, without judgment or expectations.

Listen to the sounds around you, and allow yourself to be present in the moment.

As thoughts and ideas arise, allow them to flow freely, without attachment or resistance.

When you feel ready, write down any thoughts or ideas that emerge during your meditation.

Take your time, and trust in the process.

When you are finished, close your eyes again and take a few deep breaths, grounding yourself back in the present moment.

Reflect on your experience, and let go of any judgments or expectations.

Enjoy the feeling of freedom and openness that comes from exploring your inner landscape.

All of the artists I have chosen employ deliberate repetition, variations within a framework, and an element of chance. I produced these pieces in an hour and yet they are plausible variations on their work. Not all attempts were as successful. It is, however, evident that one could, for example, generate a large number of these to hand out to an audience at a performance so for participants to perform and evaluate the results.

AI has been rapidly developing this year and ChatGPT is only an early step in this decade, likely to be dominated by AI. Serious artists need to ignore the bad art and forge ahead. AI image and text generators are the tools of our time.