Looking through my own library of books from occupied Lithuania, I realized that a broader audience was likely unfamiliar with the story of the Lithuanian SSR’s artistic revolution in the 1970s, a bold and audacious deviation from the traditional narrative of Soviet-controlled artistic expression is the midst of the Cold War that has yet to receive proper treatment in the West.

By 1960, the Politburo had become concerned about the rising cultural influence of the United States worldwide, particularly in Europe. In particular, they were concerned about the use of art in the ideological war with the capitalist and democratic West. As Serge Guilbaut’s book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art elucidates, the United States Information Agency and the CIA weaponized modern art as a form of soft power.

… the battle against communism promised to be a long and difficult one, and one which for want of traditional weapons would require the full arsenal of propaganda. The war may have been a “cold war” but it was nonetheless a total war. Accordingly, art, too, was called upon to play its part.

Guilebaut, 173.

The dynamism and unpredictability of Abstract Expressionism served as an apt metaphor for the freedom and innovation promised in the American way of life, a foil to the strictures of Socialist Realism that dominated the art scene in the USSR during the 1950s. The ossification of Socialist Realism, and the understanding of it outside the Soviet Union as rigid, formulaic, and bereft of individual expression was a contrast to the immediate post-revolutionary environment when Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Bolshevik Soviet People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education, recognized the power of avant-garde art as a tool of propaganda and influence and advocated for Agitprop experiments inside during the heady days of “War Communism.” Soon, seeking to convert the European avant-garde to Communism, he dispatched El Lissitzky to Western Europe to spread the gospel of Constructivism and funded publications like Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet to showcase the exciting new direction of Soviet art to the world. Such radical projects were soon suppressed in favor of a romanticized cult of the worker in Socialist Realism. But with Soviet leaders facing the rising cultural influence of the United States, after the ouster of Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and Premier Alexei Kosygin tasked a committee to investigate how to reverse the USSR’s declining ideological popularity. Evaluating the profound impact that Western art was having on the global art scene, the committee recommended a course of action as unprecedented as it was strategic, designating the Lithuanian SSR as a special zone for artistic expression. There were a number of reasons why Lithuania was chosen: First, the small Baltic nation—literally the westmost part of the Soviet union—had long been westward looking, but the impenetrability of the Lithuanian language to Russian and the relatively small Russian minority—when compared to Latvia or Estonia—meant that if these developments got out of control, they could be contained. The committee moved slowly and, at first, chose to let Lithuanian architects lead the way. Notably, works like Elena Nijole Bučiūte’s Žemėtvarkos projektavimo instituto rūmai (Institute for the Organisation of Land Exploitation) and Vytautas Čekanauskas’s Parodu rūmai (Art Exhibition House), both built in 1967, received positive reception locally, in Moscow, and abroad.

The decision to designate the Lithuanian SSR as a special zone for artistic expression signified a clear departure from the norm. It was a move that challenged the traditional model of centralized control over artistic production and expression that had characterized the Soviet cultural policy since the days of Stalin. The Soviet leaders were acutely aware of the potential for art to be a vehicle for dissent and for the expression of ideas that were contrary to the state ideology. Yet, they believed that the potential benefits outweighed the risks. They hoped that by fostering a vibrant and dynamic art scene in the Lithuanian SSR, they could demonstrate the cultural vitality of the Soviet Union, and perhaps even influence the global discourse on art and freedom. The Lithuanian SSR was thrust into the limelight. Artists were suddenly given the freedom to explore new artistic currents, to challenge the established norms, and to engage with their counterparts in the West. The impact of this decision on the Lithuanian art scene was profound and transformative, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the country’s cultural history.

Already as early as the mid 1960s, American Fluxus leader George Maciunas reached out to his Lithuanian counterparts—notably composer Vytautas Landsbergis—to establish links between New York and Vilnius (see, for example, this 1991 article in Artforum by Nam Jun Paik). Maciunas would struggle to return to Lithuania, his efforts at obtaining a visa always subtly thwarted by Moscow authorities, who believed his brand of art could ignite ideological difficulties, but nevertheless, he managed to secure visits in the early 1970s from Western artists, notably Joseph Beuys, photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard (who photographed peasants in the countryside), and land artist Robert Smithson.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, photographs from Lithuanian countryside, taken and exhibited 1970

Robert Smithson exhibit, Vilnius, Lithuania, 1971

Joseph Beuys Exhibit, “Labas Rytas, Lietuva,” Vilnius, 1972

For Lithuanian artists, this newfound freedom was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it provided an opportunity to break free from the shackles of socialist realism and to explore a multitude of artistic currents prevalent in the West. On the other hand, it posed new challenges as they had to navigate this unfamiliar artistic landscape while still operating within the overarching political framework of the USSR. Brilliantly, the directorship of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union understood this danger and encouraged artists to work in anonymity, under pseudonyms or in groups, a process which they claimed avoided the bourgeois cult of the individual, but that also protected them from trouble should the winds of politics change. For six years, from 1970 to 1976, the Artist’s Union organized annual thematic exhibitions that received remarkable attention in both the local scene and in the West, even as they were hardly known in the larger Soviet Union or East Bloc due to concerns about the ideological content of the work.

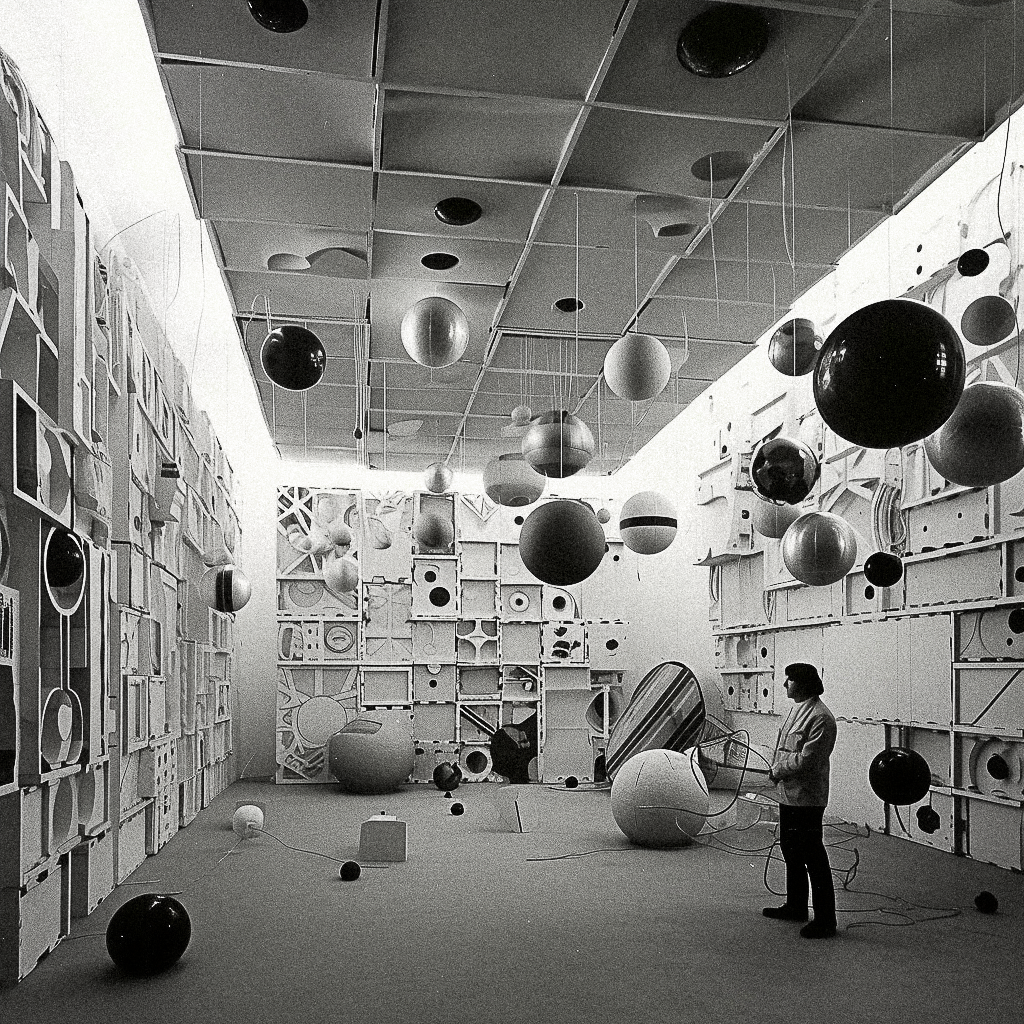

1970. Objektai/Objects

The 1970 show was an ambitious start to the cycle of annual exhibitions, itself inspired by the 1966 Primary Structures Show as well as by Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes. Giving this work an appropriate didactic Marxist twist, artists set out to critique the processes of production, consumption, and overaccumulation in society. Exhibit halls throughout Vilnius were filled with large stacks of blank boxes and museum storage areas were opened to visitors. The show proved wildly popular with artists but confounded both the public and the authorities, who urged caution and discipline in future exhibits.

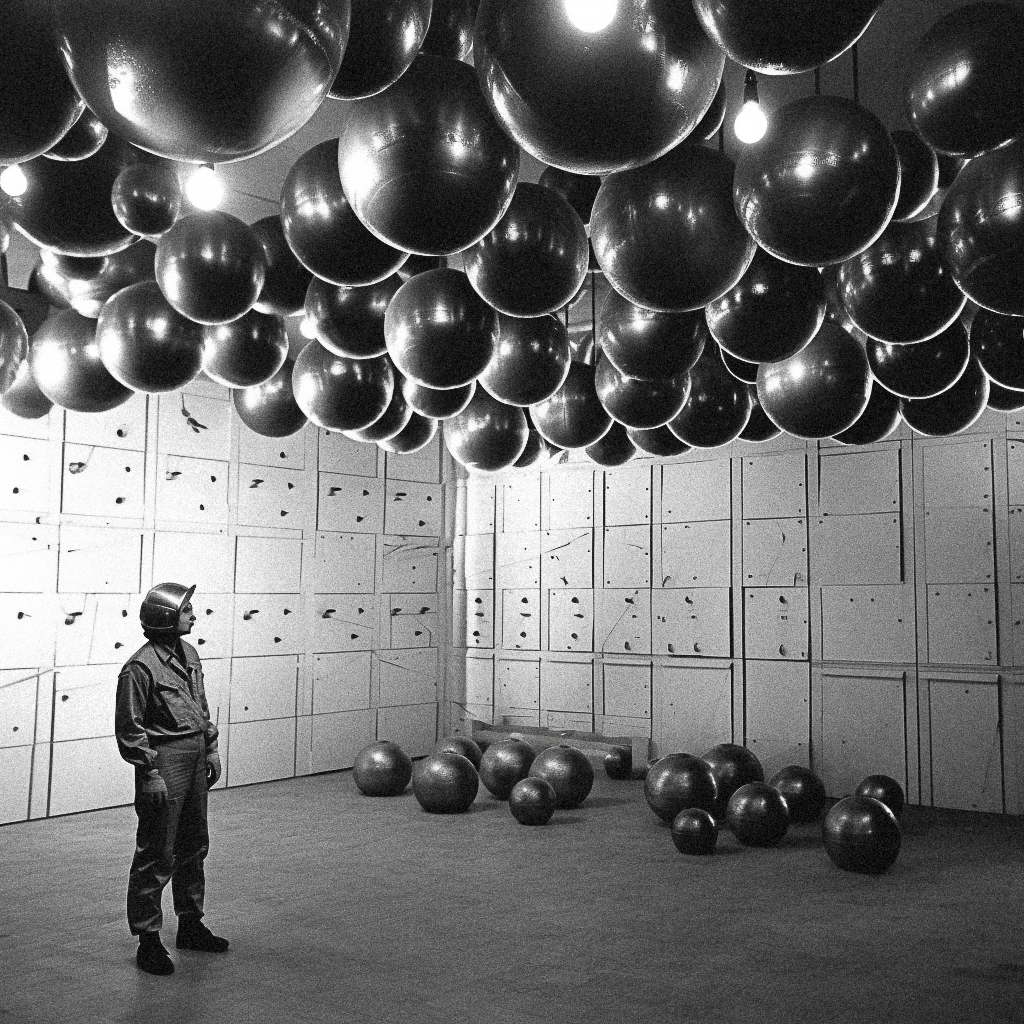

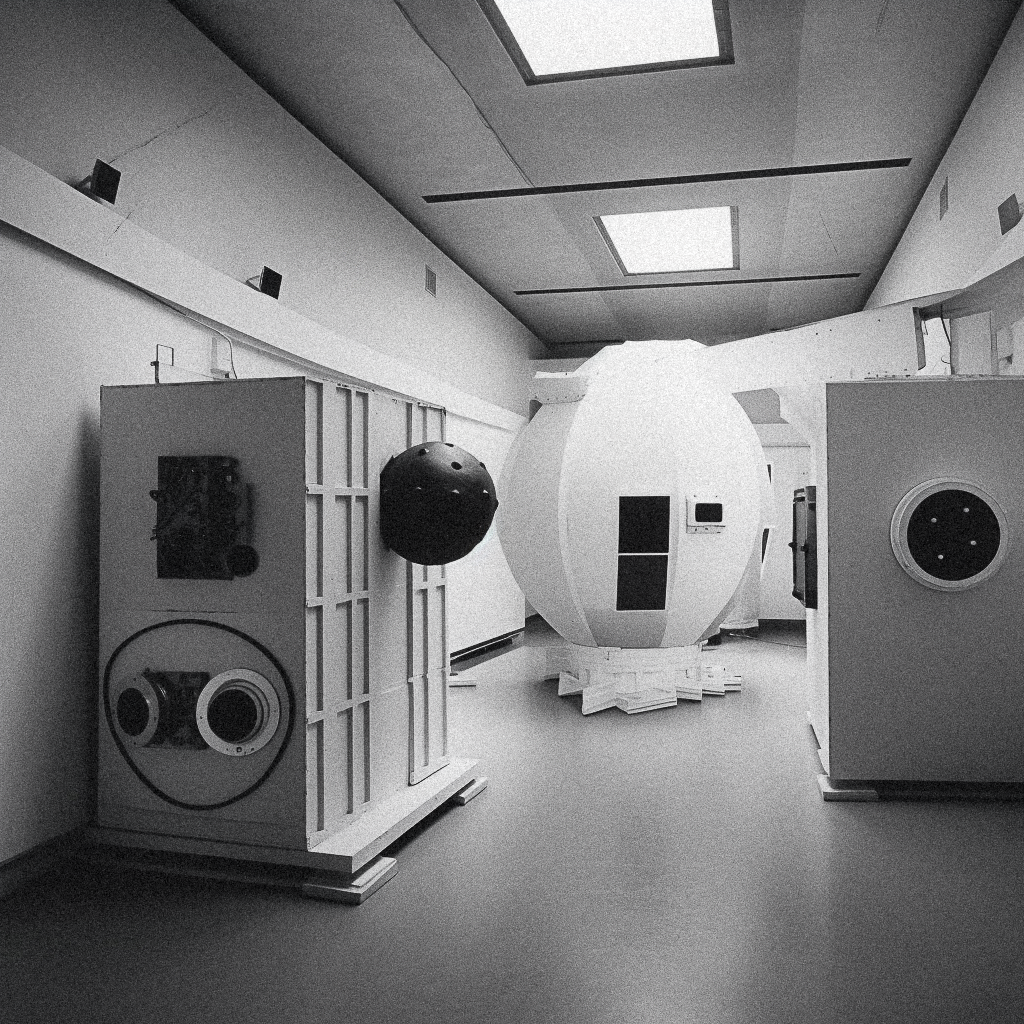

1971. Kibernetica/Cybernetics

Hoping to appeal to sympathetic forces in the nomenclatura, the Artists’ Union invited Aksel Ivanovich Berg, Soviet scientist and head of the Scientific Council on Complex Problems in Cybernetics to lecture on the topic to artists who would then work on the theme throughout the city. Unsure of how to apply the problems of cybernetics to art, Berg—who was also a radio engineer—showed a slide of Nicolas Schöffer’s Tour Cybernétique (Cybernetic Tower) in Liège, Belgium, a project that responded to data from its environment. Artists constructed their own interpretations of the Tour Cybernétique throughout Vilnius and added other interpretations of how art might engage with the topic, including an early work of sound art that Landsbergis included in the show. Returning to see the show, Berg was puzzled by the work, but glad for the attention to his field.

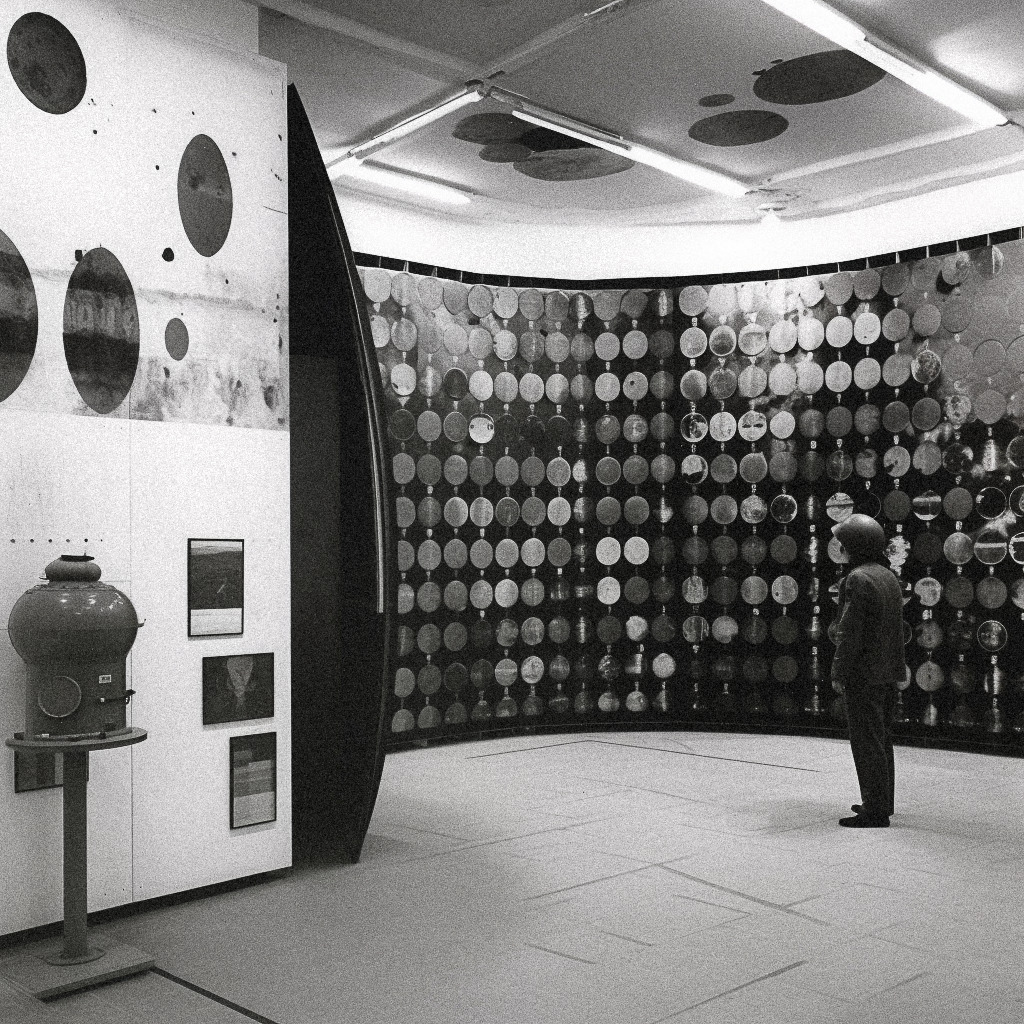

1972. Mokslas/Science

Seeing the potential for aligning the exhibits with themes popular with the government, the Artists’ Union tried again in 1972, this time with science, building on Lithuania’s role as a major research center for electronics. Nevertheless, the display of a crashed mock-up of a space capsule proved highly controversial in the wake of the fatal 1971 accident of Soyuz 11 (no Russian crewed spacecraft flew again until 1973) and the overall Soviet failure to reach the moon. Leaders of the Artists’ Union were accused of subversion and only high-level interventions by sympathetic Politburo members saved the experiment.

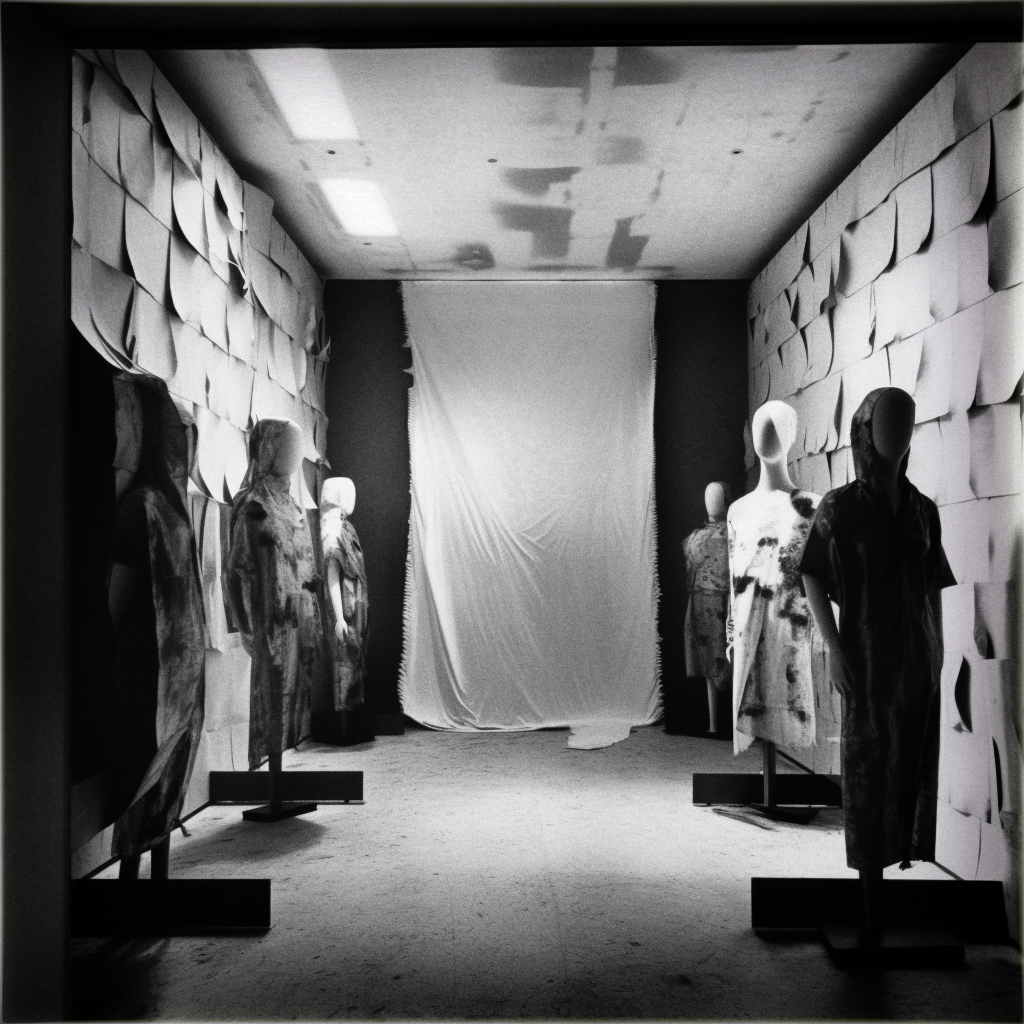

1973. Feminizmas/Feminist Art

With fingers burned, the Artists’ Union set out on a surprisingly risky path, an exhibit of feminist art. This proved wildly successful in the West and did not lead to terrible consequences back home, although as with the 1970 Objects show, the conceptual nature of the show meant it was confusing to locals. Feminism proved to be a risk worth taking and inaugurated a series of shows in which both organizers and artists flew ever closer to the sun.

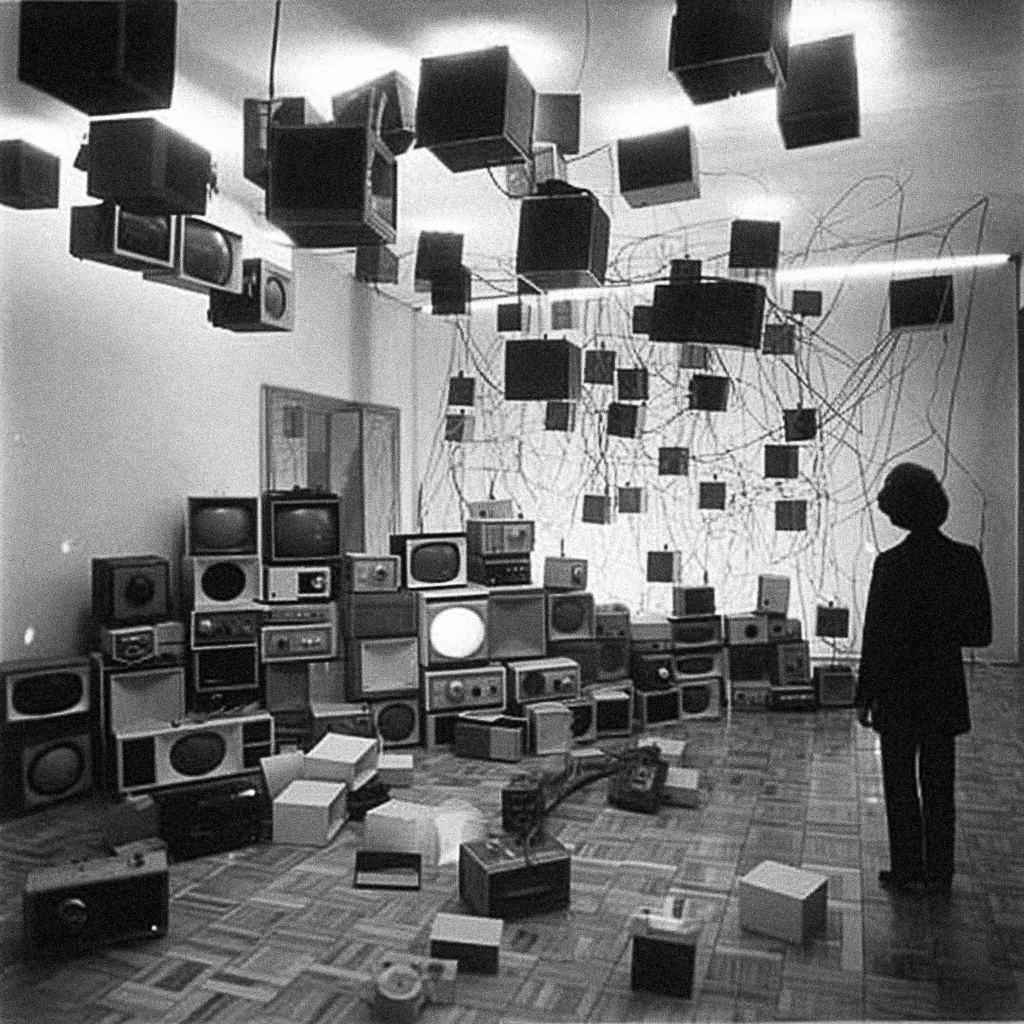

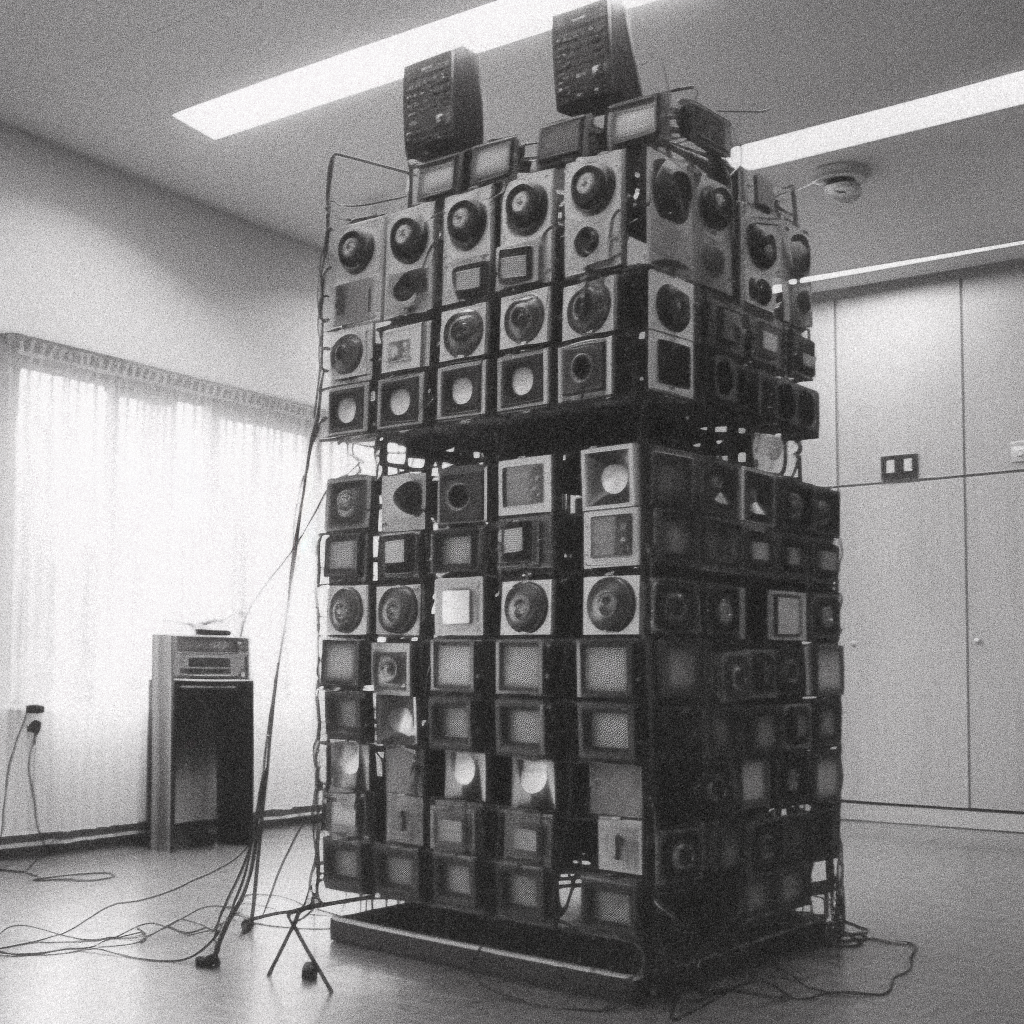

1974. Televizija/Television

Hoping to finally reach the public more broadly, the 1974 exhibit revolved around the phenomenon of television. Television, by this point, had become popular in the USSR and Lithuania was a major center of television manufacture in the Soviet Union. Video art had become popular in the West and the Television exhibit sought to capitalize on the phenomenon while critiquing the televisual spectacle. Echoes of both the Objects and Science shows could be felt in this exhibit, which achieved reasonable success with the local populace and authorities.

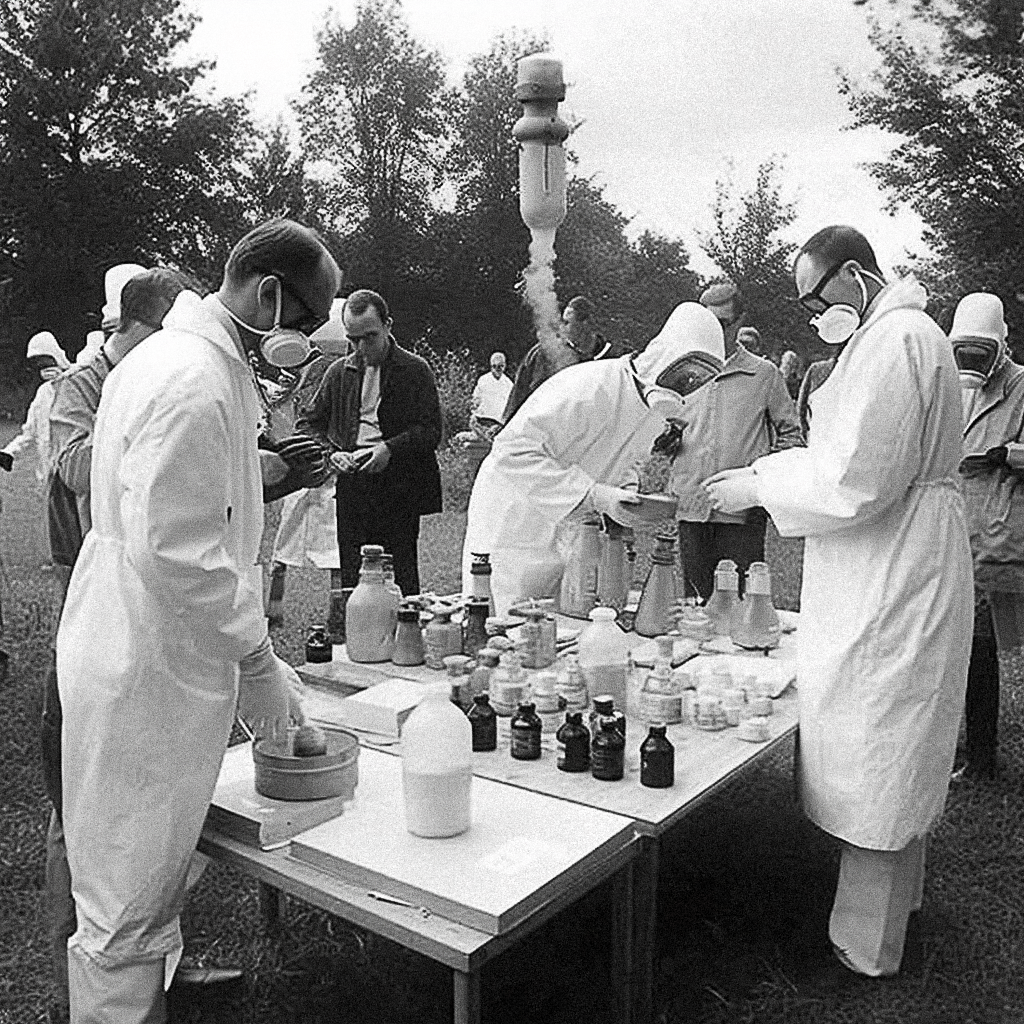

1975. Aplinka/Environment

1975 saw the beginning of the end of conceptual art in 1970s Lithuania. The construction of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant, which had begun in 1974, had led to widespread discontent, and the Environment theme was co-opted into a protest by a group of young artists against nuclear power. Although the project drew more attention than ever from the West, inspiring protests against nuclear power and chemical contamination in West Germany and the United Kingdom, it unsettled the Soviet authorities and they placed the Artists’ Union on notice that their methods were becoming ideologically unsound.

1976. Vaiduokliai/Ghosts

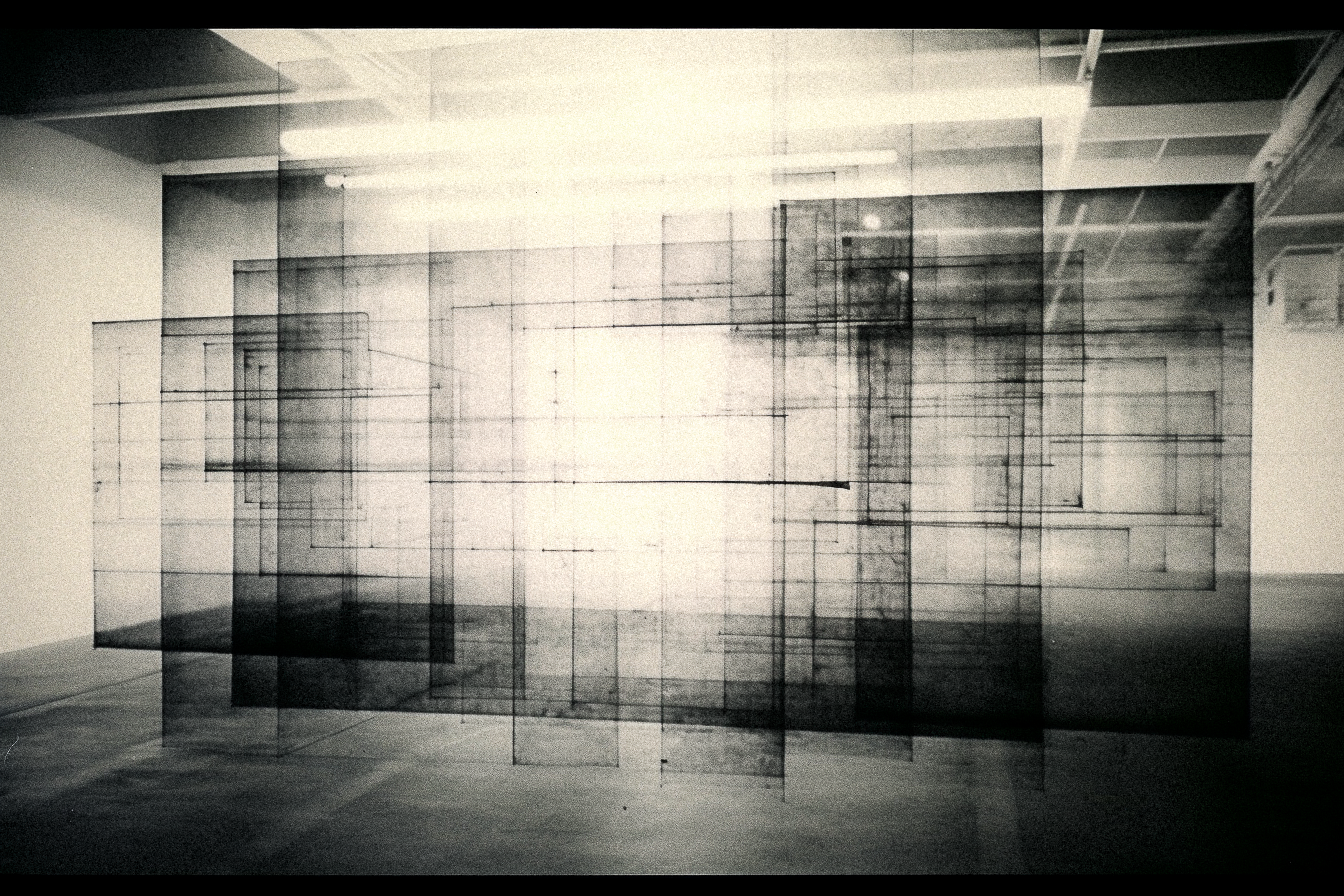

During the organization phase of the 1976 exhibit, which was initially supposed to be on abstraction, the Artists’ Union was notified that this was the last in the series of experimental art projects. The controversy over the Environment exhibit had proven to be too great and the program had earned the disapproval of Brezhnev himself. As a coda, the organizers swiftly rethought the theme around the concept of ghosts and haunting. Many of the works were of a strange, abstract quality, with fabric scrim and translucent panels suspended throughout the exhibition halls. “Paintings” made of oxidized steel lent the exhibit a further funereal air.

In the fashion of failed Soviet experiments, the exhibits of the 1970s were not spoken of again, at least not in public, and it would take until Lithuanian Independence and the foundation of the Contemporary Art Centre by Kestutis Kuizinas in the early 1990s for conceptual art to find a new, more permanent home in Vilnius, but at some level, these experiments were never forgotten and helped give rise to a new generation of radical artists.

This is the second of three drafts of Critical AI Art works that I am publishing this week. AI Art that seeks to do something, not just create NFTs for profit is incredibly time-consuming and like the first piece on Pierre Lecouille, this project took months to of work to this date. For my friends in Lithuania, this piece, in particular, is likely to seem incomplete and I fully accept that. But as I stated in the afterward to the Lecouille piece, the rapid development of AI image generators—not to mention the kitsch being produced by them—means that sitting on this work for longer will simply make it stale, so here it is, incomplete but in the public sphere.

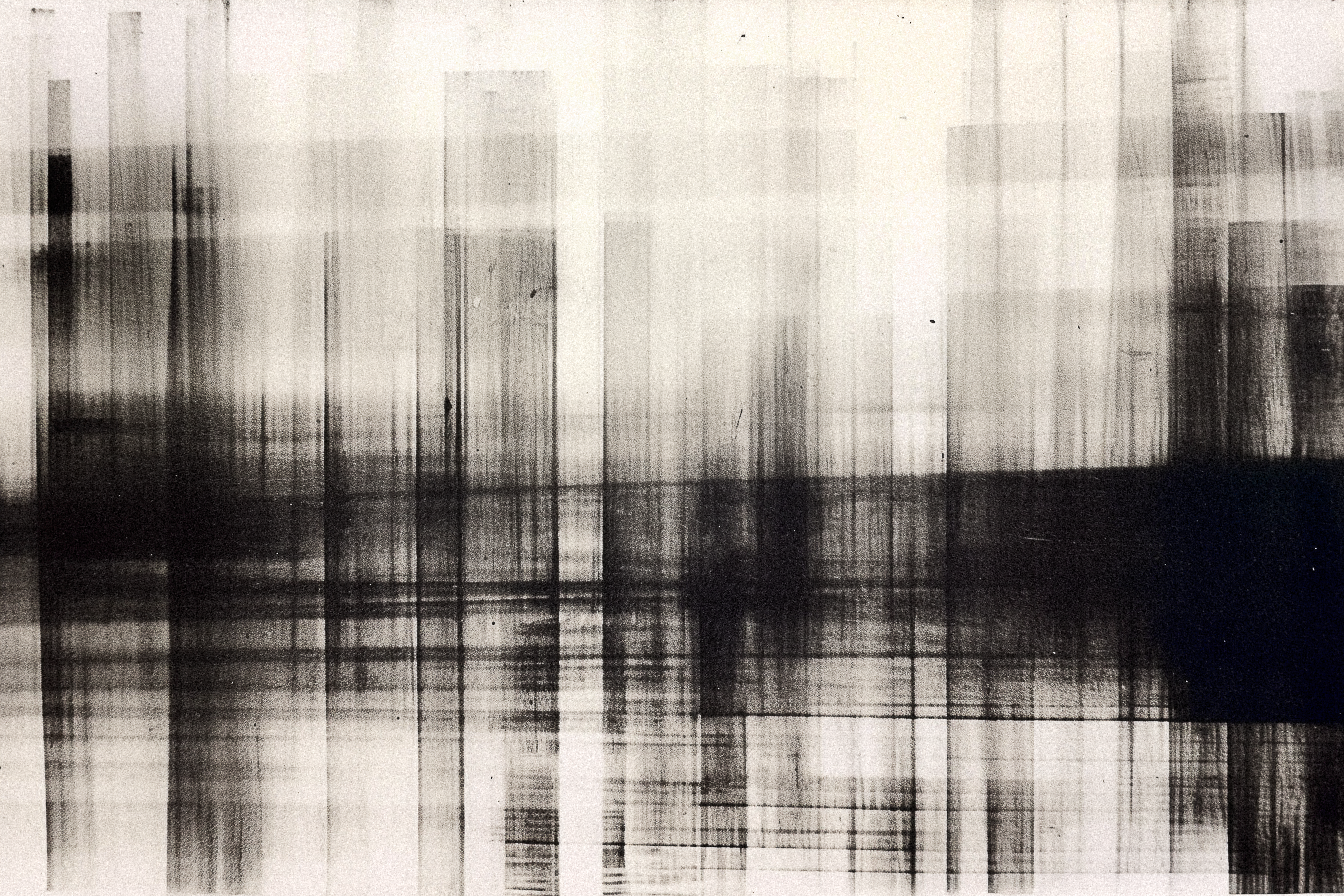

As with all of my AI Art pieces, this work began with an experiment in prompting. Initially, the images returned did not resemble Vilnius or art that I could ever envision in Lithuania. Over time, however, Midjourney has proven much better at producing uncannily appropriate imagery. Once a basic outline emerged and I could begin refining this work, it developed a threefold significance for me. First, it points to the impossibility of work like this in the repressive atmosphere of Soviet-occupied Lithuania in the 1970s. Imagine what radical thought has been lost to the machinery of oppression. Second, the rewriting of history recalls the chronic desire to rewrite history (and to fake imagery) in the Soviet Union and, to a lesser but still real extent, in post-Independence Lithuania and the West in general. Finally, this work has a personal meaning to me, a spirit photography of an era of art that I knew only as a child in 1970s America and that I nevertheless miss deeply as well as a country that always existed as a lost Other until I finally was able to visit in 1991. There is no word for “Ostalgie” in Lithuanian as there is in Germany, since the Soviet times were, for Lithuania, a time of great oppression by a foreign power—unlike East Germany, which was very much the jewel in the crown for the East Bloc—and this is not that, rather this project is, finally and foremost, a way of working with the way a particular place and time has haunted me over the years.