It snowed last weekend; just a few inches fell and it was soon gone, a reminder of how profoundly our climate has changed for the worse in our decade here at Highland House. Still, for a few days, there was snow and I was drawn to how it covered the stone wall in front of our house. I admire the wall every time I leave the house for the outside world, whatever the season.

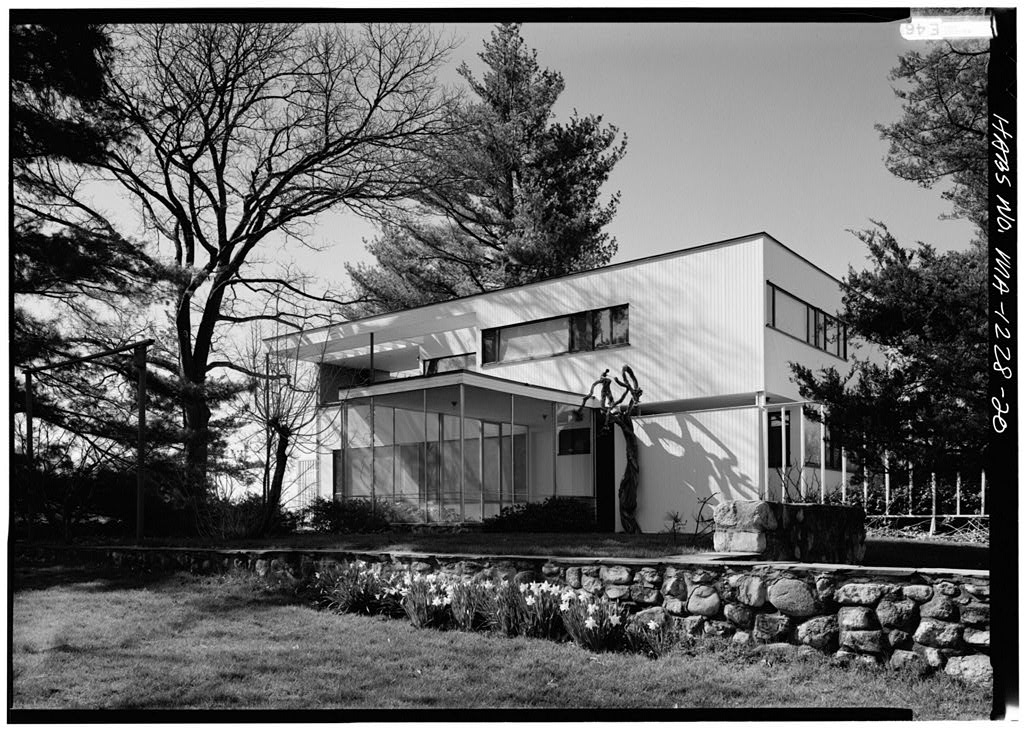

We built the stone wall four years ago, but it looks like it could have been there for two centuries. That was the goal. Before that, the hill had been held back by a decaying wall of pressure-treated wood painted a rather unpleasant mauve taupe that you can see in the photograph above. This wall is not a fence: it does not separate two plots but rather holds back the steep hillside to accommodate the flat area containing both the driveway and house. It is an artifact of politics, a constant reminder of poorly thought-out town planning. The zoning code in this area dictates that houses be set back fifty feet from the property line, notwithstanding any slope. Since our tract has a roughly consistent 30% pitch (an elevation drop from 500′ to 450′ over 165′), that means the front of the house is well below grade level, rising from a man-made plateau roughly 30′ below the road. Of course, it would make far more sense, from a financial and ecological perspective to site the house closer to the road, thereby minimizing the driveway and leaving the rest of the property as a vast hillside garden, but the town planning board refused to make such compromises so colossal amounts of energy and material had to be expended to construct a house here. Likely, the town’s real goal all along was discouraging any construction.

When the time came to build the wall, multiple contractors and the engineer all wanted to either rebuild the pressure-treated wall or put up an engineered stone wall. I refused, it would be dry stack. How about a “dry stack” veneer in front of a row of cinder blocks, they said? No, and no. It was going to be a traditional dry stack stone wall. It was my money and I won out in the end. Previous owners had installed pavers and low walls of Anchor Bergarac concrete block in front of the house. These cheapened the look, much as the tired fake lanterns and the ridiculous pink solid stain on mahogany siding did, turning a pleasing late-midcentury modern house into a pedestrian suburban ranch. We ripped out the pavers and the low walls at the same time, integrating the hardscaping at the front of the house with the construction of the retaining wall. This year, we replaced the last of the Anchor Beragac block which made up a stair on the side of the house with natural stone as well, completing the project.

The stone the wall is built from is called “Pennsylvania Colonial” and comes from somewhere in Pennsylvania, or at least from a supplier in Pennsylvania. I would prefer something more of the place, but the Passaic Formation dominates the geology of this area and that is composed of sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, all of which are weak stones with high porosity, much more prone to breaking. Much of the Upper West Side of Manhattan and Brooklyn is constructed out of this material and this has caused headaches since the nineteenth century. Soon after construction residents were observed rubbing their stone facades with wire brushes to remove disintegrating parts. Since the 1930s, composite materials have been used to seal and finish weak brownstone façades in the city, but obviously, this is inappropriate for a stone wall. Even if the local stone had proved durable, nearby quarries have long ago ceased operating, thus even if I wanted it, there would be little option to build with the stone from the immediate vicinity.

Pennsylvania Colonial is a bluestone, another kind of sandstone, but it is stronger than the local brownstone. In coloration, the blue-gray Pennsylvania stone reminds me of the stone walls of New England and New York, which were such a common sight in my teenage years in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts. We had a dry stack stone retaining wall in front of my parents’ house and that wall still stands today on Ice Glen Road, over a hundred years after it was built, but most of the walls across New England were built to demarcate property lines, constructed from the stone that inevitably came up as fields were plowed by early farmers both initially and as a result of annual frost heaving. Since a large amount of stone can be found in this area of New Jersey—or at least on my property—I wonder what happened to all the rocks and boulders that surfaced here over the years. New Jersey has many fewer stone walls than New England and New York, a fact that was noted in the 1872 US Government Department of Agriculture publication, “Statistics of Fences in the United States,” which observed that 90% of the fences in Essex and Bergen County were post-and-rail construction (post-and-rail dominated the state although hedges of Maclura pomifera, the Osage Orange, a small deciduous tree originally found in Texas were employed “to some extent” in the central part of the state, a practice more common to the Plains states).

The walls of New England were not just walls to me, they were markers of another era, a time in which the area was heavily agricultural, when the green of the Berkshire Hills was from grazing meadows, not trees. This seemed improbable to me when I first heard of it; how could the towering trees on the mountains of Stockbridge, Massachusetts be that young? Surely these were primeval forests from the days of the native Americans. But this was contradicted by the stone walls I would find on my hikes deep in the woods. Where had the houses gone? What had gone on here? A budding historian at thirteen years of age, I went to the town hall, where the staff generously indulged my inquisitiveness by showing me old aerial maps. Here, I saw for myself the shocking truth: the forested area of Stockbridge had grown greatly, not shrunk, over the decades. In the 1930s, the plot next to my parents’ property had hosted five downhill ski trails for the Stockbridge Ski Club. Fifty years later it was a forest. A friend from California would refer to the woods of the Northeast as “the jungle,” noting how quickly human-built landscapes disappeared.

Later in life, when I visited Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, I noticed the stone walls in the landscape surrounding the house, especially to the west, below the hill the house sits on. These too once marked farmland, before being engulfed by forest. As Johnson expanded his estate by purchasing surrounding plots, he thinned the woods, allowing the stone walls to become visible again from the windows of the Glass House. If the jungle could swallow up the traces of human activity, it could not obliterate the enduring walls.

Johnson saw the stone walls, as well as the 14 follies and structures he built on his property as “events on the landscape.” Of the forest, Johnson had the following to say, in his usual provocative tone:

But, so, the forest. The forest was at me all the time. New England is a rain forest. That’s one of my favorite topics. You are enclosed in New England with trees. Have you ever been to New Hampshire or to Vermont or Maine? There are no big trees left; they were cut a long time ago. There are no fields because the farmers couldn’t make their plows go through the stones. And they all went out to Ohio where they’re meant to go. So it’s left New England covered with lousy trees that grow up the crick so you can’t see anything but still don’t make trees, you see. So in this very unfriendly atmosphere that a rain forest gives you, what you need is a machete and an axe and a saw. And armed with those tools, you create landscaping in a negative way, unlike the British, who in their great things of the 18th century, had no trees. There were no trees at Versailles, none, you see. They all had to be planted and worked out. I didn’t have to plant my trees; they were there. I had 200-year-old oaks and things all prepared for me. I had to select. I had to say this can be a copse, this can be a single tree, this has to be cut. And by ruthlessly doing that, I have the basic background, the interesting feature, watching your eyes follow through the forest to a wall beyond or not, or infinitely. And you have open fields, which is to me the best.

Interview conducted on behalf of the National Trust for Historic Preservation by Eleanor Devens, Franz Schultz, Jeffrey Shaw, and Frank Sanchis, https://theglasshouse.org/explore/landscape/

Johnson was not alone in his admiration of stone walls In the middle of the twentieth century, architects of the Northeastern seaboard like Elliot Noyes, Marcel Breuer, and Walter Gropius would juxtapose their highly technological modern houses with a more rustic approach to the landscape. In his 1938 house in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Gropius found himself in a blend of open fields and wooded areas, typical of the New England landscape and only a few miles from the future home of Deck House, the company that built Highland House (I wrote more about the history of Deck House here). This setting provides a stark contrast to the house’s modernist architecture, characterized by its clean lines and functional design. The integration of the house with its surroundings is deliberate, aiming to create a seamless interaction between the indoor and outdoor spaces. Large windows and an open terrace serve as interfaces between the interior of the house and the natural world outside, allowing for ample natural light and a sense of continuity with the landscape. The landscaping around the house, while appearing natural and unforced, is carefully planned. It features local plants and trees, adhering to Gropius’s belief in the importance of local materials and natural aesthetics. The use of native plants not only integrates the house into its New England setting but also reflects a sustainable approach to landscaping, a concept ahead of its time.

Overall, the landscape at Walter Gropius’s house in Lincoln, Massachusetts is a testament to the integration of modernist architecture within a natural setting, embodying principles of simplicity, function, and harmony with the environment. It demonstrates the principle of decorum in architecture, which involves the appropriate use of design elements according to the function and setting of a building. In classical and Renaissance architecture, decorum was a guiding principle that dictated the suitability of architectural styles and elements based on the building’s purpose, location, and the social status of its occupants. This principle was extensively discussed by Renaissance theorists like Vitruvius and Leon Battista Alberti. In the context of country residences or villas, the use of rustic elements was often considered appropriate as they resonated with the natural surroundings and rural character of the site. The use of rustic elements in countryside architecture during these periods can be seen as a precursor to the embrace of stone walls by modernists in the Northeast. These architects embraced the natural and sometimes irregular qualities of materials to complement and enhance the rural setting. A story about Johnson illustrates this: the architect, who was well known for wearing Saville Row suits while in the city, famously surprised visitors to the Glass House who dressed in suits to visit only to find him in a polo shirt and expressing mock surprise that his guests had dressed for the city when they were deep in the New England countryside. The principle of decorum, therefore, serves as a historical context for understanding how architects have long adapted their designs to suit the specific characteristics of their environment.

In building my wall, I also thought of decorum. I thought of the history of the area, both natural—below is a photograph of a boulder in Apshawa preserve, a haven for native plants restored by Leslie Sauer of Andropogon Associates, some fifteen miles away—and cultural, e.g. the stone walls of New England and New York. I also thought of our midcentury modern house, clad in rough-sawn mahogany siding, which I was having painstakingly restored by a craftsman at that very point in time.

There is a tradition to stone walls and, unless you disassemble the wall to uncover the foundation, you would have no evidence that our wall had been built in the 21st century. After our mason, Bart Piotowski of Pol-Max construction in Tom’s River, laid a deep concrete foundation and used an earth mover to construct the wall, the method was otherwise the same as it would have been in the 18th century.

Gravel was poured behind the wall above a drainpipe to ensure hydrostatic pressure would not built up.

Elsewhere on my property, I have built simpler stone walls with my own hands, following traditional methods. In all cases, it takes time and skill to build the wall. When the building inspector from the township came for the final inspection. He was impressed, declaring: “Long after you, me, and this house are gone, this wall will be here.” But it’s not just the dry-stack stone wall that ties us to history, the method of its construction is largely the same. Although Bart used an earth mover for the largest stones, they still required careful thought and placement, a massive jigsaw puzzle made from the very stuff of this Earth.

See my earlier post on the plants that live in the alpine condition immediately above the wall.

Throughout, the stone walls allow water to seep in—and through—them, allowing plants to colonize the spaces between the stones and, in the case of mosses and lichens, even the stones themselves, making the walls come alive. Many of the mosses and lichens came on the rocks from the quarry, riding on their microhabitat for hundreds of miles to my property. Over time, the stones will break down, but that sort of time is not measured in decades or even centuries, rather it is measured in millennia. So too, chipmunks find homes in these rocks, happily scurrying in and out of burrows that they have excavated in the depths of the hill beyond.

Cruelly, I did cave to conformism and eventually removed this, but it will come back somewhere else.

All this is in sad contrast to the typical kind of hardscaping generally done in this town, which is all straight lines and concrete or stone set in mortar, impermeable to water and, paradoxically, more prone to damage from frost and moisture: without anywhere to go, forces will act against such a wall, eventually breaking it. In addition, dry stack walls can flex slightly with ground movement, making them less prone to cracking than rigid concrete-set walls. This flexibility is particularly beneficial in areas with freeze-thaw cycles or minor ground shifts. Dry stack walls are easier to repair than mortar-bound walls. Stones can be replaced or re-stacked as needed without the need to mix and apply new mortar or concrete. Sadly, most landscape architecture today tries to ape architecture instead of working with the stuff of landscape: stones, soil, and plants. Landscapers are even worse, all turf and Berberis thunbergii (Japanese barberry), the ugliest and most banal of invasive plants.

Man—and it is usually the male of the species—has done enough damage to the land. We have enough hard surfaces and straight lines in the gridiron of Manhattan, in the highways that cross the country, our houses, and even in the Jeffersonian grid that demarcates the land of industrialized agriculture in the middle of the country. We have enough impermeable surfaces. We do not need more hardscape. I’ll take Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty over Michael Heizer’s Double Negative any day. One ties us to the land, the history of Mesoamerican earthworks, and deep time, the other is just a man with his toys, fighting the landscape to make a statement. Let’s try to find better ways to work the land and heal ourselves in the process.