los angeles

Back to Infrastructure

Christopher Hawthorne has a largely favorable review of The Infrastructural City in the Los Angeles Times today. I was delighted by the attention although disappointed by how he got tripped up in some naïve assumptions. Unfortunately even though ACTAR had sent him my contact info, Hawthorne rushed his article to press, missing his opportunity to think through the book’s main points.

I laughed out loud at Hawthorne’s opening lines, in which he suggests that the book would have "a tough time steering clear of the remainder bin" if it weren’t for the stimulus package or that I didn’t expect that infrastructure would be trotted out as part of the stimulus plan, that I was taken by surprise.

It’s true that infrastructure was once the least sexy of topics, a term barely used in English as late as the 1960s, but as Ian Baldwin, my former student at Penn, observed, it spread widely after the publication of America in Ruins, co-authored by economist Pat Choate and Susan Walters. The authors of that report suggested that some $2.5 trillion would be needed just to keep the country’s infrastructure functioning at a constant level into the mid-1990s. Infrastructure, as a concept referring to a bundle of physical service networks, became visible in its collapse. That money was, of course, never allocated.

Over the next two decades, infrastructure continued to rise in the public eye, in large part because, as our book points out, it is in a state of constant failure. This is something that virtually all of us experience. Angelenos, navigating over-crowded streets and freeways at a snail’s pace, understand it viscerally. We’ve also come to understand that there are going to be no great new projects: only architects and reporters seem to believe otherwise. The immense expense of construction, empty government coffers, and NIMBYism will take care of that. But the New-Bad-Future-right-now of infrastructure defines our cities today, much as the lifestyles of Banham’s ecologies defined the urbanism of his day. As humans and objects interact ever more directly (look at the actor-network theory of Bruno Latour, for example), the lives of these systems become more and more important.

Architects have long been interested in infrastructure. Starting in the Renaissance, copies of Vitrivius’s Ten Books on Architecture typically had Frontinus’s essay on aqueducts as an appendix. Later on, Piranesi likely drew inspiration from the Cloaca Maxima, the Roman sewer, for his Carceri. Infrastructure is a lost fantasy object, taunting us with the suggestion that those aspects of the city that escaped from architecture could once more be under our purview. In Los Angeles, the avant-garde scene came together at the West Coast Gateway competition of 1989. If the West Coast Gateway project never got built, Gary Paige’s reconstruction of an abandoned railway depot into the downtown SCI_Arc building a decade later is the most inspired large project in the city in decades. In designing the building Paige drew on the theories of Stan Allen, now Dean at Princeton, and an advocate of thinking about architecture and urbanism in infrastructural terms. Infrastructure is hardly a topic for the remainder bins, at least not for architects.

As for the stimulus plan: there was certainly some rhetoric last fall suggesting that a new era of WPA projects was upon us, but as I’ve pointed out, this is hardly the case if one actually looks at what’s in the plan, as I did here. Hawthorne isn’t a political reporter, so he missed this, but it’s crucial and there’s on excuse for not doing your homework.

The Obama administration is not spending a significant amount of money on infrastructure. My definition of infrastructure is broad—certainly broader than Hawthorne’s—but this plan does not initate much new funding for infrastructure, not unless you count the construction of hospitals (note to unemployed architects: there will be a bit of work building hospitals) or digitizing health care records. The plan is an amalgam of tax cuts bundled with triage for various government programs that were underfunded during the Bush administration. Those are the facts. Whether Obama changed his mind or infrastructure was an easy-to-understand term he deployed as bait, this is by no means the return of the WPA.

Perversely, this may not be a bad thing. Take a look at Eric Janszen’s article "The Next Bubble" at Harper’s. Back in February of last year, months before the crisis had revealed its full dimensions to the unwary, long before the rhetoric about the stimulus plan, when Hawthorne was still hunting remainder bins looking for books on infrastructure, Janszen cautioned that infrastructure might be the cause of the next bubble.

But the money spent on last fall’s bailout, together with the funds allocated for the stimulus plan, pretty much ensures that the government is going to have its fiscal hands tied for some time to come. In other words, the stimulus plan will not only fail to fund further large infrastructural initiatives, it will prevent them from being built in the first place. An infrastructural bubble isn’t coming.

Now I do anticipate that in the coming years industry will have some success with getting funds allocated to subsidize construction of supposedly sustainable energy sources. Most of these aren’t sustainable either environmentally or financially, and once the economy shifts again, the results may look something like this abandoned solar energy plant built in the early 1980s, then dismantled and left to rot like a field of dying date palm trees when the financial models failed.

[Image via CLUI’s Land Use Database]

The real infrastructure to watch will be the network. It’ll continue its growth, the invisible layer of soft infrastructure exerting more and more influence over our lives even as it becomes more distributed and more privatized. As Rick Miller and Ted Kane point out in their chapter on mobile phones, it is by no means positive that the public interest has been placed in the hands of private interests. This is a challenge that the country needs to confront and I see little political will to do so. Hawthorne’s failure to mention it suggests that it’s still beyond the scope of a story in a Sunday paper. That’s a shame.

The end of Hawthorne’s piece is flat-footed. Instead of confronting the consequences of our conclusions, he appeals to the fantasy of infrastructure as the next architectural object, trotting out the idea that architects need to be involved in the design of the new infrastructural America.

In the unlikely event that somehow a burst of hard infrastructure takes place, I hardly think that this will save architecture. Why would a cash-strapped government pay for design now when it has never done so before? You could say that the great turning point in infrastructure is took place at the George Washington bridge when the engineers decided it looked fine as it was and decided not to give it a stone cladding. But we’re not even brave enough for that today. The palm tree on our cover says it all: a cell phone tower is not designed by Frank Gehry, it is designed to look like a palm tree. Now we’re probably the better for it: the host of architect-designed subway stations in Los Angeles were largely an embarrassment. If by some miracle architects get on board with infrastructure, NIMBYism will make sure that new infrastructure would look even more contextual. Imagine the rise of cell phone trees disguised as mission bells throughout Los Angeles, hardly what any of us want.

I was happy to see Hawthorne finish his article with a pot-shot at the architect-as-icon. It’s nice that is trickling down. But Hawthorne doesn’t go far enough with his recommendations for the profession. Please save us from OMA-designed off-shore wind farms. Architecture needs to re-invent itself in the face of the challenges of contemporary life. As Hawthorne suggests, architects need to take a page from engineers and embrace anonymity. More than that, they need to apply their tremendous imaginations and skill to reprogramming the world of network culture into something new and fantastic. Go read bldgblog, look back at what Andrea Branzi and Bernard Tschumi wrote decades ago: these guys had it right. Now more than ever commonplace thinking about architecture’s role will be fatal.

In the coming week, I’ll follow up with a post containing my piece from Volume Magazine’s "bootleg" issue of Urban China in which I draw together the links between the book and the economic stimulus plan and suggest some more directions.

the infrastructural city

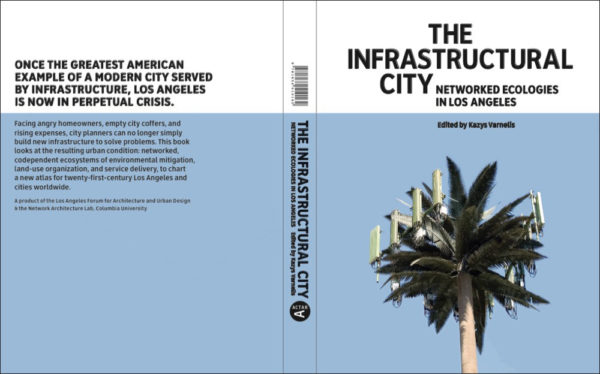

The Infrastructural City has been published and is now on its way from Spain to the United States. Those of you in the EU may already be able to get it from ACTAR. Other readers can preoder their copies at Amazon.com.

This book has taken a long time to get to press, but I’m delighted that it will be in the stores by Christmas. Much more important is that I am confident that it will be read for years to come. Our goal was not modest: we set out to replace Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles. The Architecture of Four Ecologies as the key text for understanding the city urbanistically. Looking at the finished product, I can’t help but think that we accomplished this goal. I wouldn’t say this if I didn’t feel this was true.

Unlike Banham, who wrote in a simpler time, I realized that a project of this scope needed to have not one author but many, guided by an overall organizing framework. Thus, I commissioned some of the most intelligent observers of the city to write about areas in which they specialized. The process of editing these texts and collecting images wasn’t easy. Unlike some editors, who merely collect disparate pieces together and then put their name on the project, I wanted these pieces to read as if they were part of one book. Authors retained their voices, but I set out to give the book an overall sense of coherency. At times, the texts were a sea of red pen. Similarly, we worked to give the book a stylistic coherence by choosing images carefully and, when needed, I would go out and shoot my own images. The Netlab also provided every chapter with carefully rendered maps, again seeking coherency between the essays.

Where Banham saw ecology as the basis of his understanding of Los Angeles, I sensed that the key to understanding the city (or indeed, any other city today…for unlike Banham’s effort, this book is as much about any city as it is about Los Angeles) is infrastructure.

Modern architecture was obsessed with infrastructure. It served as the basis upon which modernism could realize its plans. The greatest American example of a modern city served by infrastructure, Los Angeles is an ideal case study. Today however, Los Angeles is in perpetual crisis. Infrastructure has ceased to support architecture’s plans for the city. Instead, it subordinates architecture to its own purposes. The city we uncovered is a series of networked ecologies, complex interlinked hybrid systems composed of natural, artificial, and social elements, capable of feedback not only within themselves but between each other.

We hope you will take a look.

On Philip Johnson and Sex Machines

I will be speaking on Tuesday, September 23rd at UCLA’s Hammer Museum at a panel discussion entitled "Architecture and Seduction

Bachelor Pads and Sex Machines." I’m excited about the talk, which gives me a chance to focus on Johnson’s Glass House in some depth, and about the panel discussion with Paulette Singley, Frank Escher, Renata Hejduk, and Norman Millar. Please come if you are in the Los Angeles area. For more of my work on Johnson see Philip Johnson’s Empire and We Cannot Not Know History. And don’t forget about my new book coming out this fall, The Philip Johnson Tapes: Interview with Robert A. M. Stern. It’s a steal to pre-order at Amazon.

los angeles from helicopter

The end of August at the Netlab brings the end of the Infrastructural Los Angeles project and little by little it’s getting assembled into a book. From now until publication (hopefully by Christmas!) I will be showing off projects from the book.

To start, take a look at Lane Barden’s trilogy of aerial photographs of Los Angeles. Lane and I taught at SCI_Arc together and it’s a privilege to have his work grace our book.

Three series of photographs, all taken from helicopter, show the Alameda Corridor, the Los Angeles River, and Wilshire Boulevard. Together these demonstrate the force of these

entites—in turn devoted to moving objects, fluids, and people—as they shape the city in their very different ways. Together, they suggest that it is not the urban plan as much as the infrastructural project that has shaped—and continuous to shape—the city.

Although you will have to purchase the book to see these in print glory, you can see a selection (together with other great work by Lane) at his Web site.

curating the city

It’s rare that I like a Flash site, but The Los Angeles’s Conservancy’s Curating the City impressed me. At present, the site consists of an interactive map of Wilshire Boulevard that allows you to look back at the the history of that sixteen mile long street in detail. Even though I lived on Wilshire for a decade, I learned quite a bit from the site.

infrastructural city prospectus

Little by little my summer book projects draw nearer to completion. Here, as a teaser, is the text that ACTAR is publishing in the next catalog, together with some photos I took to accompany it.

Los Angeles: Infrastructural City

Kazys Varnelis, editor

Once the greatest American example of a modern city served by infrastructure, Los Angeles is now in perpetual crisis. Infrastructure has ceased to support architecture’s plans for the city and instead subordinates architecture to its own purposes. This out-of-control but networked world is increasingly organized by flows of objects and information. Static structures only avoid being superfluous when they join this system to become temporary containers for the people, objects, and capital. Featuring a provocative collection of research through photography, essays and maps, Los Angeles: Infrastructural City uses infrastructure as a way of mapping our place in late capital and the city, while remaining optimistic about the role of architecture to understand it and affect change.

A project of the Network Architecture Lab in collaboration with the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design.

[note oil wells off the coast of Long Beach in second photo from top]

paranoia, institutionalized

At the Washington Post (via Wired), you can read about yet another instance of unreasonable behavior by the post-9/11 national security state, in this case, the unlawful harrassment of a photographer shooting a random installation that turns out to be the DARPA headquarters.

Through actions such as this one—or the calculatingly demeaning but ineffectual "remove your shoes" security measures at the airport—the Bush-Cheney regime builds a regime of fear.

Then again, perhaps their fears are warranted…after all, a bunch of photographers, plane spotters, and the like, could cause a great deal of trouble.

On the positive side, I had zero harrassment while I was taking photographs for the infrastructural city book in Los Angeles, including this one, not far from city hall.

los angeles, the infrastructural city