Month: September 2011

Irish Architecture Now

Books and the Problem with their Future

The fall of old media and the maturing of new is a key aspect of network culture. Never before have the forms of media and the means by which they have been distributed and read changed so quickly.

But speaking as a historian, designer, and author (not to mention as media review editor of the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians), I am concerned about the future of media. In particular, I worry about how the formats being developed in media are evolving.

Books and periodicals have proved robust over time. It's easy to pick up a book from the sixteenth century and read it. The publications of our day, on the other hand, are posing a problem to future readers.

On the one hand, we have PDFs. Nobody seems to like PDFs and their capabilities are rather limited. They are hard to protect and easy to disseminate, making publishers wary of them (the vast majority of book piracy is in PDF). PDFs maintain the format of the printed page, which is great when you need it, but also a limitation (for example, older readers can't make the text larger). eBooks such as found on the Kindle and on Apple's iBooks stores seem to have more robust digital rights management protection but can also be hacked and freely distributed (never underestimate the book pirates: they will win in the end just as they did with music). But these eBooks are even more limited than PDFs. Formatting is quite limited and adding rich media such videos as to the text hasn't proved possible yet. These eBooks are, if anything, a step back from the PDF and even the book, becoming nothing less than some kind of weird intermediary between the scroll and the codex.

Then there are app books for the iPad, Android, and other tablet computers, such as Wolfram's the Elements or Phaidon's Design Classics. As librarian John Dupuis points out on his blog, these are visually compellling but an outright disaster for users in the long run. The model of book ownership that prevailed for so many years is now replaced by a model of licensing. Yes, it appears that you purchased Design Classics, but can you resell it? Can you give it to a friend for a birthday present? Can you take the pages in it and cut them up for an art project? Can you check it out from a library? Will you be able to take it with you if you tire of your iPad and want to move to an Android? Generally speaking, all of these are impossible.

As Dupuis suggests, some kind of open access and standards based authoring environment needs to be developed for the book world. How long will this take to emerge? When I first saw Apple's Hypercard authoring environment in 1987, I was certain that the future of the book had arrived. But now, that future has gone into the past, almost irretrievably so (go ahead, just try to open a Hypercard stack from 1987 such as the incredible Zaum Gadget).

Nor is the Web immune to these problems. HTML is limited so Web owners turn to authoring environments like Flash or content management systems like Drupal, (which serves this site). But if I stop updating this site, even if I continue to pay the bills for the hosting and the domain name servers, one day the PHP programming language or the MySQL database on which Drupal run will be updated to the point that an update to Drupal will be required. Drupal has this mantra called "the drop keeps moving" which basically means any module or extension involved in this site (and there are many) as well as the theme (or graphic layout) will break unless it is updated too. Even if someone was able to log into my site and update it, they would have to update the modules and the theme. Now, I am sure my readership would rather that I write more and update the architecture to my site less (unless that update is necessary for functionality) so I try to update as little as possible but when I do a major update, I generally devote two to three weeks to update all of my sites (audc.org, networkarchitecturelab.org, docomomo-us.org, networkedpublics.org and so on). Now I could export everything to HTML and forget about updating the site ever again. That could last a long time (for example, my friend Derek Gross died in 1996 but his site is still up) but that conversion process too is likely to take at least a week and would require a Drupal developer. Is that going to happen? Probably not.

None of this is new. The Institute for the Future of the Book has been talking about this for years now. But this is a crisis of major proportions for anyone involved in thinking about human culture in the long term and we need to make all the noise about it we can.

Regarding the Euro

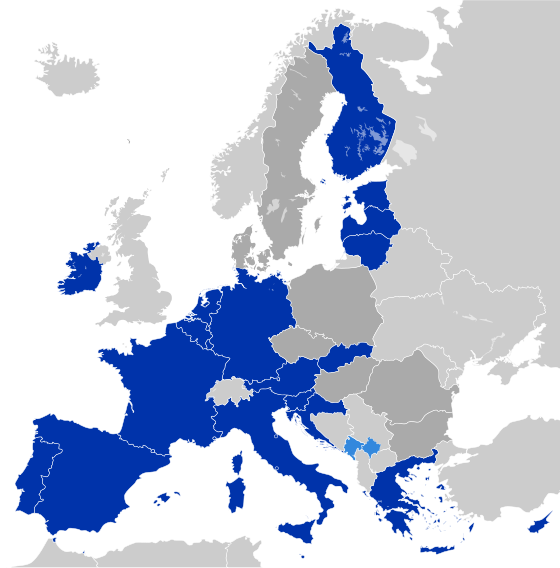

The biggest story of the last two decades has not been the opening up of China, rather it's been the creation of the Eurozone.

First off, take the size of the combined economy of the Eurozone. In terms of GDP, it is larger than China, second only to that of the US (the European Union, which also includes the United Kingdom and much of Eastern Europe would be the world's largest economy, except that it quite doesn't function as one economy).

Since I write about architecture, networks, and economy, the reason I am interested in the Eurozone is that it was an unprecedented construction of a single smooth space—to use Deleuzean terms—on a planetary scale. With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1991, it seemed to confirm Deleuze's suggestion that the old regime of enclosures was giving way to a new world of modulations. Seemingly overnight, national currencies and border controls, the most familiar artifacts of modern nationhood, disappeared to get out of the way of the rapid circulation of capital and increased worker mobility. For Eastern Europe the delight in national independence at last swiftly faded, giving way to the rush to be subsumed into a larger union again, albeit voluntarily this time, without the Soviet Union's tanks and guns.

What struck me during this period was the incredible openness of Europeans, both to each other and to those of us whose primary residence was abroad. As borders opened, so did minds. The development of the Internet went hand in hand with this opening up, allowing Europeans to go beyond the traditional boundaries of their national languages and literatures to share their ideas and learn from others at remarkable speeds. This is not to say that this wasn't going on everywhere, but it was particularly in evidence in Europe where the growth curve was very fast, a stark contrast to what was going on in the United States where thought often seemed stuck in the dark ages. For a time, Europe seemed to regain its status as the world's center of culture—as much as such a thing could exist—from the United States. Who would have thought, in 1991, that two of my books would be published by a press in Barcelona, that I would publish as much in European periodicals as in the United States, or that I would be teaching in Ireland part time?

But as the August crisis—and the last three years teach us—that growth curve got ahead of itself and Europe now faces a grave economic crisis. The economies of European countries were at different places when they joined the Eurozone and there's no way that in a few years everyone could be at the same place as Germany. Where it seemed to happen, as in the last half of the Celtic Tiger, this was largely done on debt, a condition that has now been demonstrated as impossible to sustain.

Now that the collapse of the Euro is being talked about as a real possibility, what sort of impact will this have on network culture? Is the Eurozone like the League of Nations, a great idea whose time has not yet come but will arrive, bigger and better soon? Or is it a historical anomaly? Even if globalization is a dominant economic force today, will a decade of economic stagnation couple with a collapsed eurozone lead to renewed calls for nationalism? Is the dialectic of smooth and striated space (remember, for Deleuze it was always a dialectic) about to shift again?

These are some of the biggest questions for all of us this fall.