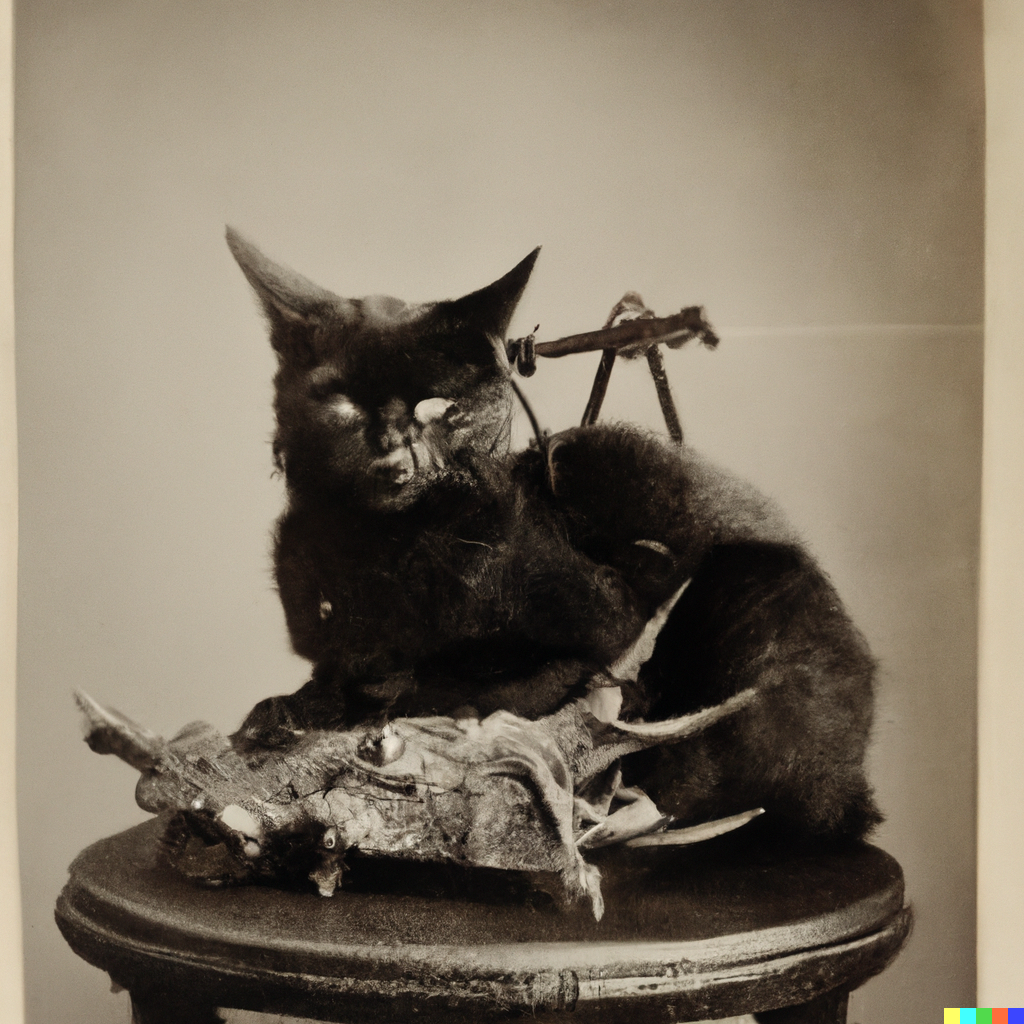

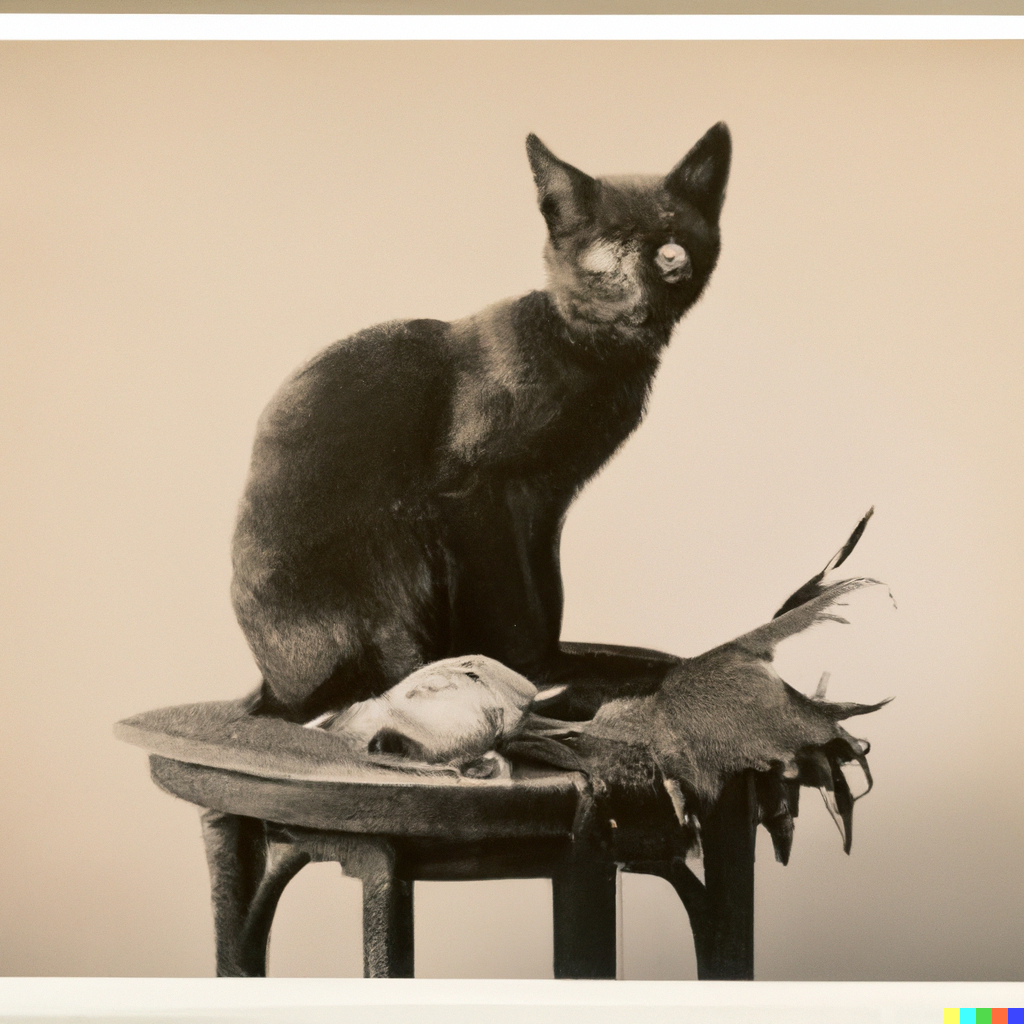

Bordentown Photographic Studio, Bordentown, New Jersey

The history of the European settlement of North America goes hand in hand with the history of occult practices—particularly witchcraft—on the continent. A large and unfamiliar land with an indigenous population that had recently died out under mysterious circumstances (now of course known to be largely due to disease brought by contact with Europeans) and in which esoteric movements were tolerated was fertile territory for individuals and groups with practices of worship at the edges of Christianity and even beyond.

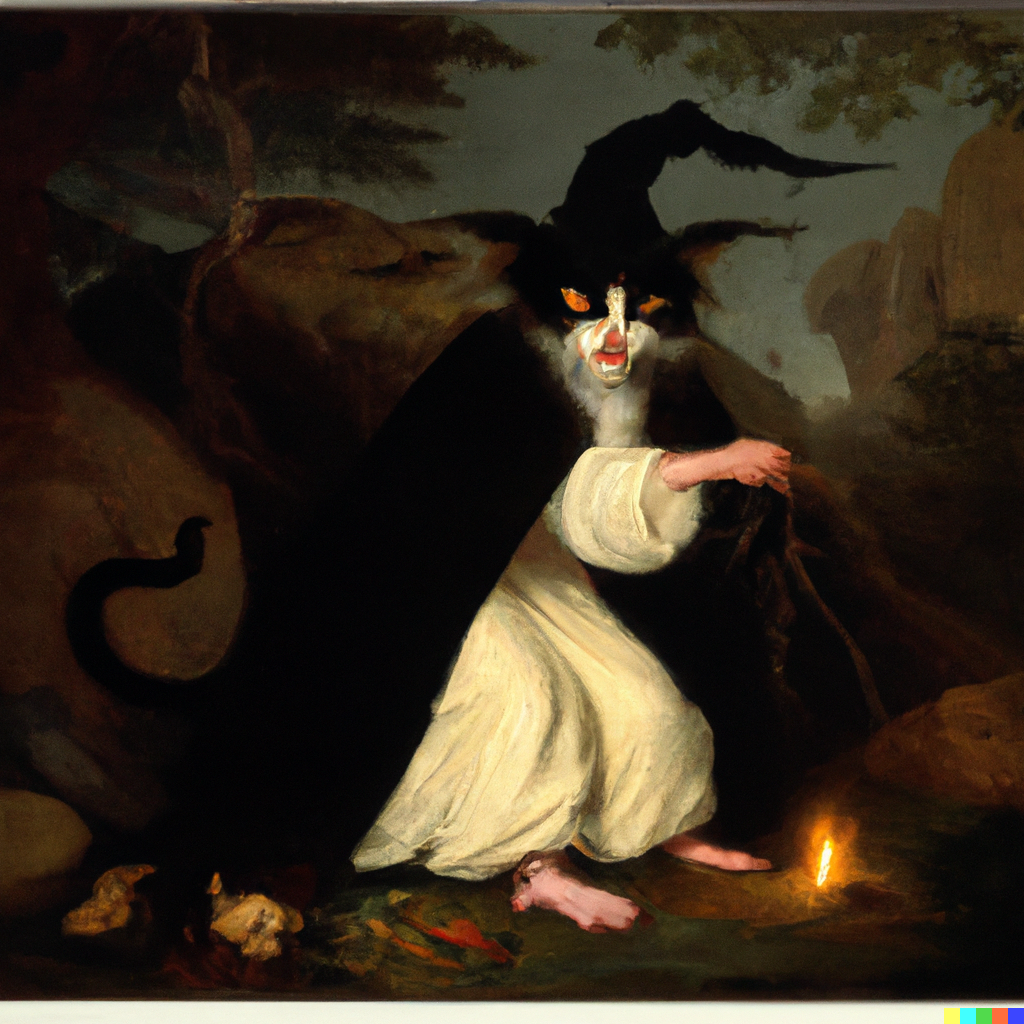

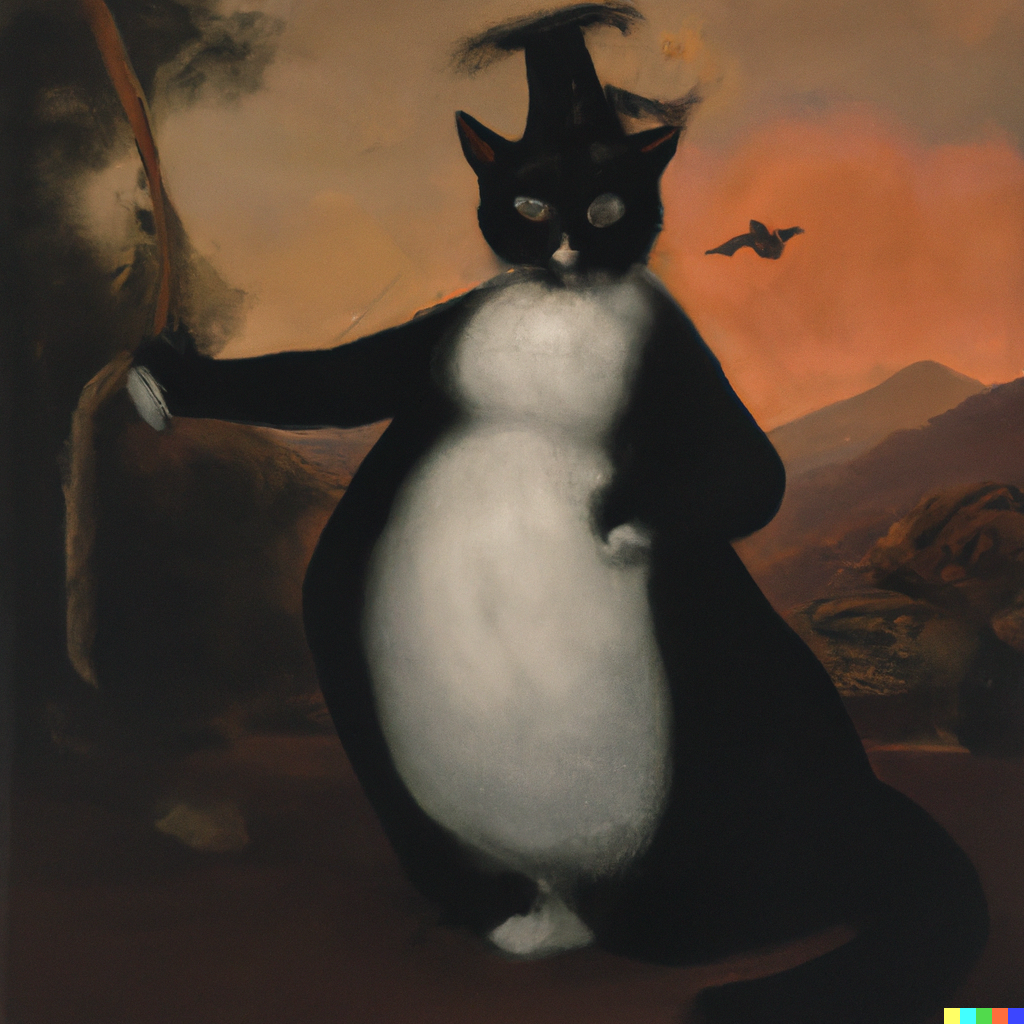

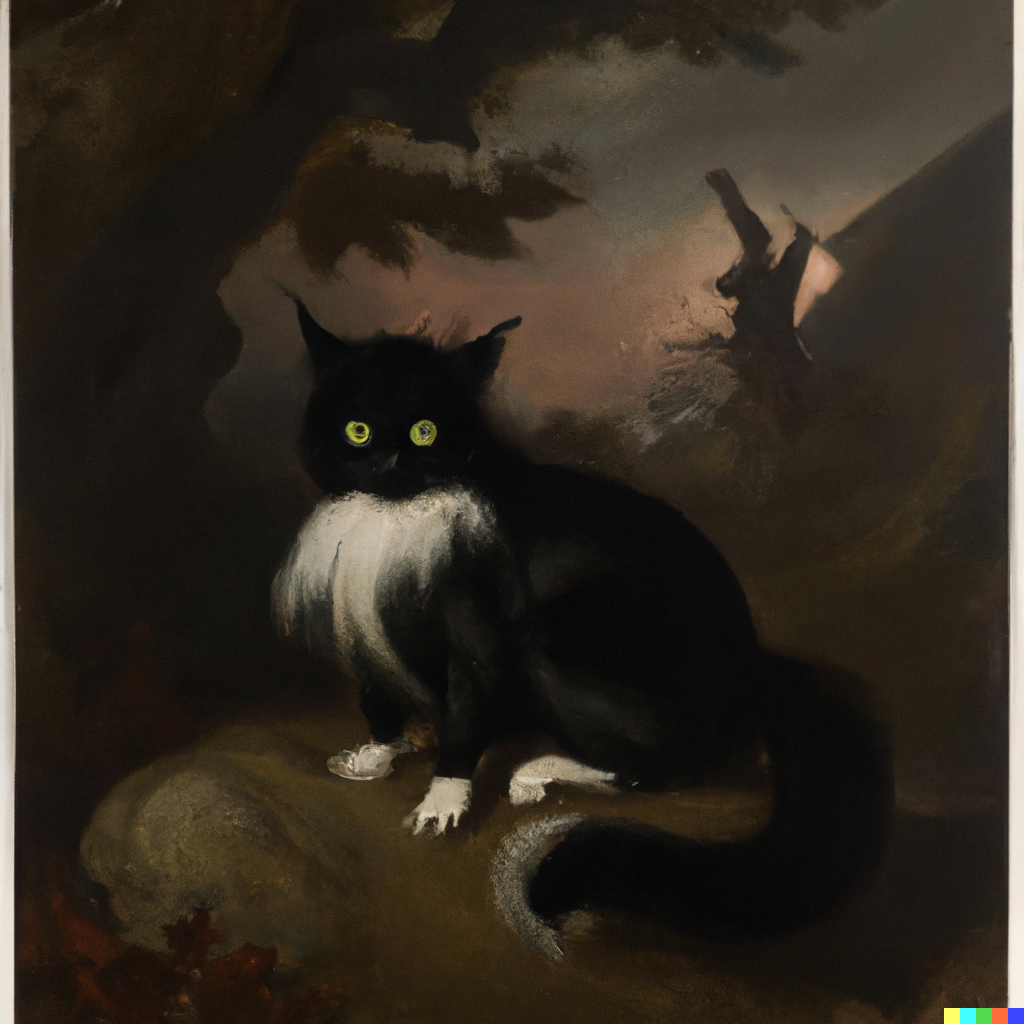

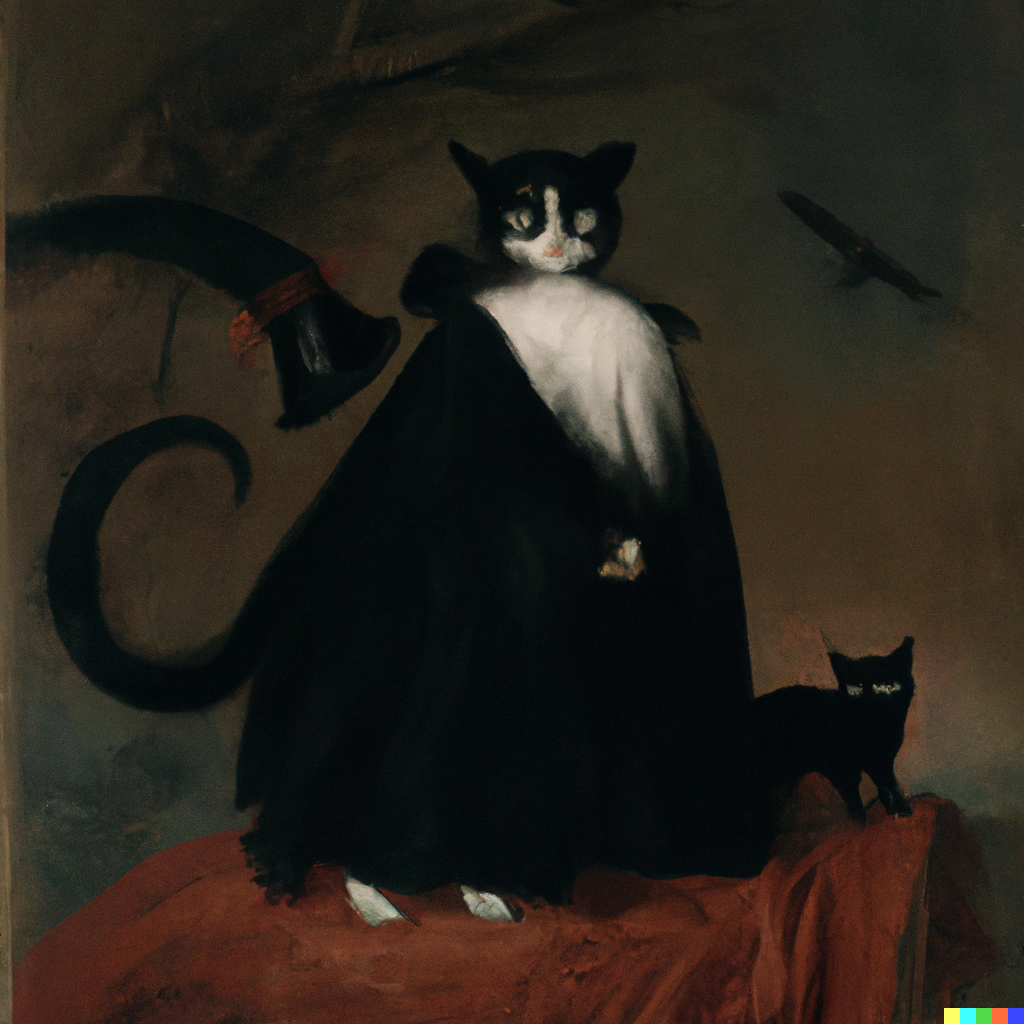

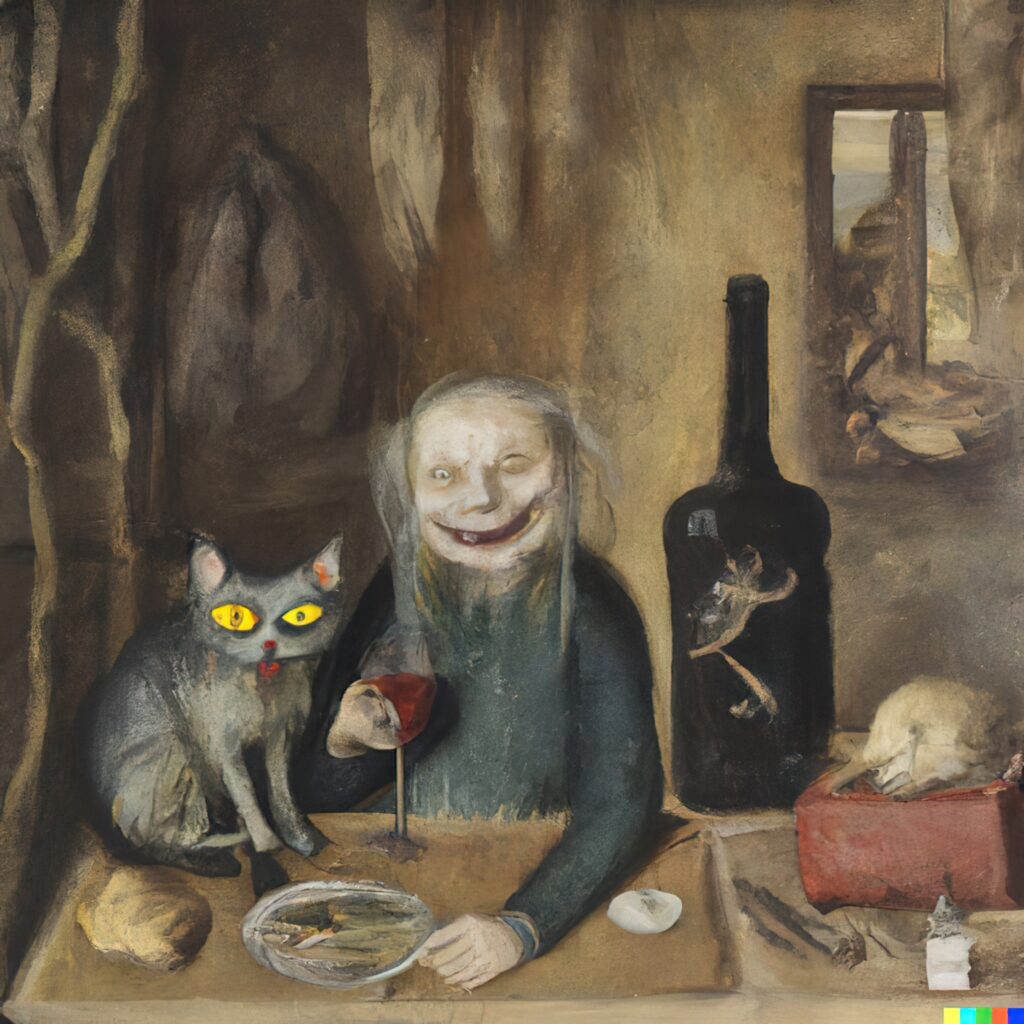

While visiting the archives at the Germantown College Archives in New Germantown, New Jersey, I had an opportunity to peruse the noted Witchcraft Collection. Visually, the record is dominated by a peculiar obsession with cats reputedly engaged in witchcraft in the “Mosquito State.” the archives contain a wealth of paintings and photographs documenting the obsession with these animals and their connection to the occult in the New Jersey.

courtesy of the Witchcraft Collection of the Germantown College Archives, New Germantown, New Jersey

Cats are the most popular pets in the world, and certainly on the Internet, but the history of domestic felines is inevitably linked to the idea of the witch’s familiar. Cats are mysterious creatures (I suppose) that are active at night (not mine, unless “active” means sleeping) and often, especially when in heat, make otherworldly sounds (Roxy is guilty as charged, albeit neutered). Given their further association with femininity, they wound up historically linked with witchcraft.

Various Portrait Paintings of Witching Cats

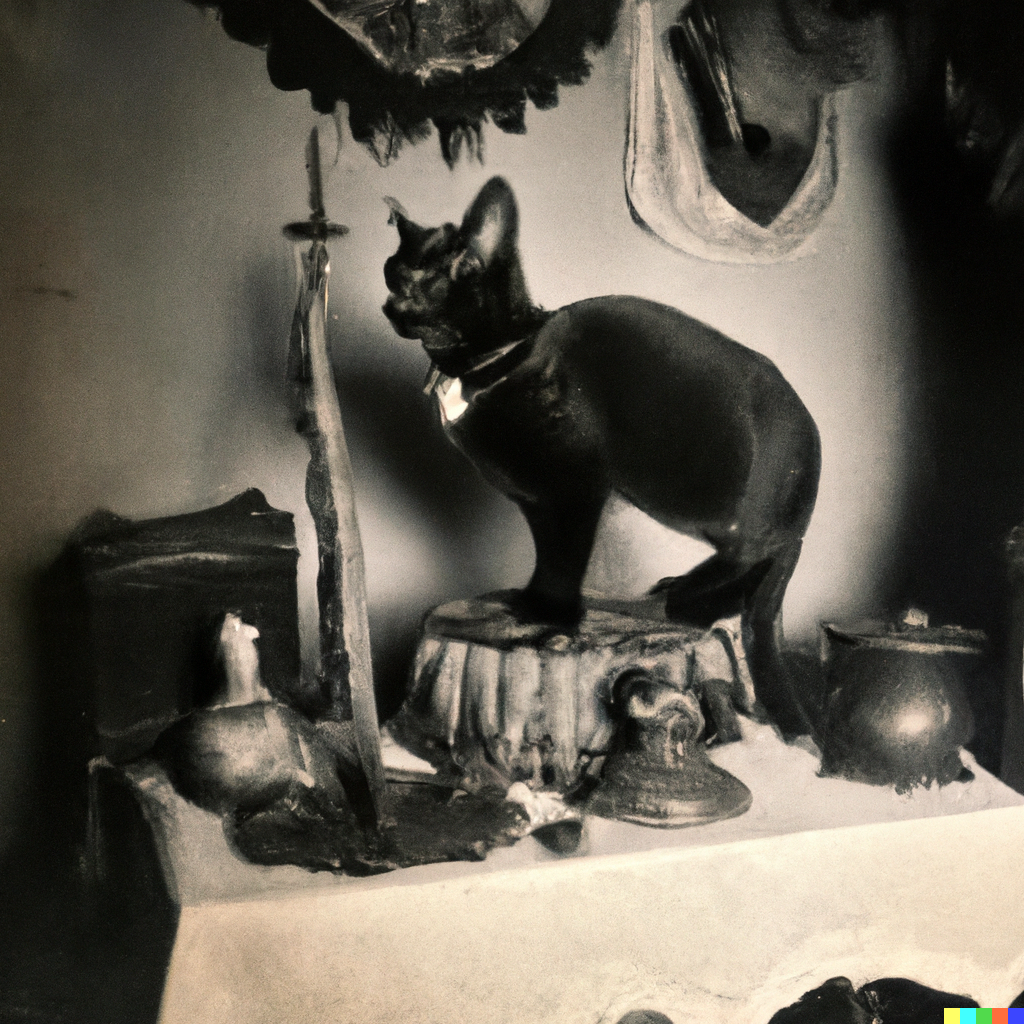

courtesy of the Witchcraft Collection of the Germantown College Archives, New Germantown, New Jersey

New Jersey, unlike Massachusetts, was not settled by a single, religious community, thus diverse faiths were tolerated here. Moreover, the colony was not originally British but originally was composed of New Sweden (by the Delaware river) and New Netherlands (by the Hudson), becoming a colony only in 1664. A land for free-thinkers, the colony embraced Huguenots fleeing from France, as well as Baptists and Presbyterians from Ireland and Scotland, as well as other faiths while Quakers crossed the Delaware from Pennsylvania and brought their beliefs here as well.

The Presbyterian leader of the First Great Awakening, Gilbert Tennant (1703-1764) came “to blow up the divine fire lately kindled there.” Thus began the colony’s early affliction with the supernatural, something made vividly clear in a young Benjamin Franklin’s accounts of the Mount Holly Witch Trials in 1730. If witches were a source of pre-revolutionary terror, by the late eighteenth century, archivist Alistair Cailleach-Crone told me, the burgeoning New Jersey merchant class in New Jersey began to commission portraits of their cats as witch’s familiars or “witching cats.” There is little documentation left of this fashion, save for this text by one Pieter Heks, 1783:

There are, and ever have been, cats and other felines, who converse Familiarly with the Spirit Realm and while some say they thus receive Power to both hurt and deceive, others claim them as happy mediums who, by their very being, keep a home free from plague, louse, and the lyke. Others, particularly, the wives of merchants in our land, keep these animals dear and hold them the pride of their house even, as the fashion holds, having portraits made of them.

Odd as it may seem, the best artists of New Jersey’s first decades as a state were involved in this work, as well as artists from the neighboring states of Pennsylvania and New York. After scolding sermons and threats from Presbyterian ministers, the fashion of Witching Cats fell out of favor among the wealthy, who soon went back to commissioning portraits of themselves, their children, their families, and noted racehorses. More than one artist was relieved.

Famed painter Benjamin West wrote unaffectionately in his notebook: “Damned cats and their owners. To the devil with them! These Jersey brutes love their animals but to have them sit for you would try any man’s patience. And half do seem to be possessed by the devil. I will never lose the scars from these accursed creatures, all claw and fang.”

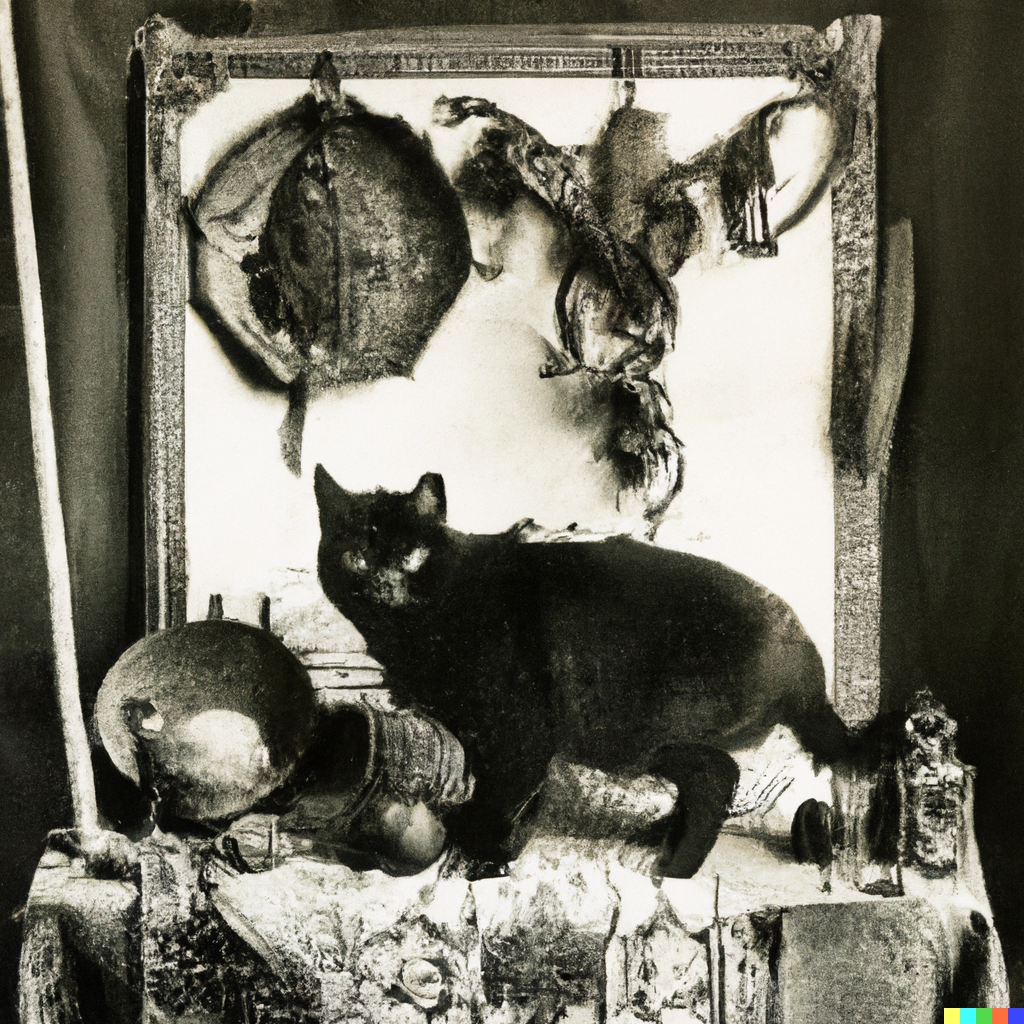

courtesy the Witchcraft Collection of the Germantown College Archives, New Germantown, New Jersey

By the 1820s, however, the Witching Cats found a resurgence in the vogue for alternately amusing and frightening paintings made by self-schooled Primitivist (or Naïve) painters in rural areas, notably the Pine Barrens. Whereas the previous paintings had largely been portrait-like in nature, memorializing specific favored pets, new paintings were often sold by itinerant painters as well as peddlers who purchased them elsewhere to sell from the back of their carts and wagons.

This work—of varying quality, sometimes remarkably comical—comprises the bulk of the collection at Germantown College. More than one observer has noted that the cats in the paintings of both periods are dominated by tuxedo (or piebald) cats, which were a common “breed” in New Jersey at the time. As Benjamin Franklin (who owned an angora) wrote in 1745, “In the dark, all cats are gray, but in the light, only the cats of New Jersey are piebald.”

In contrast to the loosely drawn images above, this mysterious set of paintings on wood panels, collected from old homes in Sussex County, from near the Delaware River is marked by stark geometries, occult symbolism, and frequently a strange elision between human witches and witching cats.

During the 1830s, a young painter from Speertown, in northern New Jersey named Theodore “Red” Baudrons (1810-1910) began a curious series of paintings in which cats were depicted in environments with strange objects that hinted more directly at witchcraft. This series, called “Cats in the Garrett” soon became controversial and he wound up leaving for New London, Ohio where he lived and worked on a farm owned by the Townsend family and instead turned to a less controversial subject, the wealthy farmers of that area.

If primitive in technique, compositionally Baudrons’s art evidences an interest in the phenomenon of “the Cabinet of Curiosities.” Precisely where Baudrons learned about the artifacts and symbolism used in witchcraft is unclear, although there have been suggestions it may have been from his sister Hattie Cunnan or perhaps his mother Diana both of whom were spoken of as “cunning women” who could cure many aliments. Baudron, about whom little more is known, also left a few drawings behind at the Townsend farm, which are mixed with the paintings in the gallery above.

Again, the fashion for Witching Cats died only to re-emerge in the years immediately after the Civil War, this time in photography. One Thomas “Namir” Bastet (he claimed Persian ancestry) set up a photographic studio in West Bloomfield, where—along with the usual photos of widows and their errant children—he took an extensive series of photographs of cats that are clearly within the Jersey Witching Cat tradition although in fairness, some appear to be just ordinary housecats. Bastet, it seems, was both a student and friend of photographer William H. Mumler, noted for his notorious 1869 photograph of well-known cat-lover Mary Todd Lincoln and the ghost of her husband Abraham Lincoln—there are suggestions that Bastet actually pioneered the practice—but also was a friend of Swedenborgian Spiritualist painter George Inness who once told Bastet of his photographs, “Namir, you really have something there.” Inness wrote that Bastet—alone among photographers—understood the vital forces in his subject matter and the first image in the slider above is of his cat, Roxelana.

Bastet’s photos often seem influenced by the compositional strategy of Baudrons’s paintings: a cat perched on a shallow ledge populated by strange artifacts, but Cailleach-Crone suggested to me that this may have to do with deeper folkways and practices now lost to time. Compounding the supernatural nature of these images quality, the photographs of the day had long exposures, requiring a stillness an awake cat could hardly be expected to meet, resulting in a blurred image that gives many of them an especially otherworldly quality.

Between the 1890s and 1920s, one Michel LeChat of Orvil, in Sussex County, produced a series of photographs that can only be described as disturbing, with the cats generally in much better focus than anything Bastet could produce, but with the cats often seeming to adopt human poses, wearing human clothing, and most perplexing and disturbing of all, possessing prehensile hands instead of paws.

Together, the witching cats reveal to us the nature of the most haunted state in the Union and the peculiar genetic misfits (by this, of course I mean the cats, not the citizens) that have inhabited it to the present day. Long before the Internet, our fascination with cats—as well as with folk horror—was already common. Please visit the Germantown archives, or failing that, visit Dall-E 2 or Midjourney to learn more about these images and how they were made.

Often, AI image generators such as Dall-E 2 and Midjourney fail in amusing ways. A while back, I was trying to make images that would look like a formal nineteenth century portrait of an ancestor of our cat, Roxy. This failed, but the image appeared rather evocative of ‘folk horror‘ and that, after a few more iterations, I posted some “witching cats” to Instagram and some of my most valued friends asked that I produce more.

But if I initially thought of this as a lark, there was something compelling about these images and the ability of Dall-E 2 (and later Midjourney) to produce such content. While at the National Gallery, I chanced on a book on art and spirituality and, later found a few books on the topic of spirit photography.

Spirit photography, which apparently independently arose in France, England and (under William Mumler) in the United States was soon exposed in the press as a fraud perpetrated by unscrupulous hucksters. The result called into question the truthfulness of photography, which had appeared to be an objective, even scientific, depiction of reality. Naïve takes on AI image and text generators have portrayed these tools as calling into question the veracity of the images and text that we find on the Internet. But these questions are old and run deep. Artificial Intelligences prompt us to rethink what is real and what is false and should force us to remember, that seeing isn’t be believing.

As far as Spiritualism, it turns out, that this theological movement was often a form of resistance to dominant structures, frequently by women. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote,

The only religious sect in the world, unless we except the Quakers, that has recognized the equality of woman, is the

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Volume III, 1886. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/28556

Spiritualists. They have always assumed that woman may be a medium of communication from heaven to earth, that the spirits of the universe may breathe through her lips messages of loving kindness and mercy to the children of earth.

Seeking to dissociate themselves from the occult, both feminist and art histories have consciously eschewed the supernatural as frippery, but doing so is a mistake as art critic Eleanor Heartney elaborates,

Indeed, you could say that the decoupling of spiritualism and the occult from the history of progressive ideas mirrors their decoupling from the history of art. But […] the occult is deeply entwined with American art and identity.

It is often said that belief in mysticism, occult energies, and immaterial realities grows stronger in times of trauma. It is easy today to scoff at the obvious fraudulence of some 19th century spirit manifestations. But during that time of social, political, and philosophical upheaval, there was a widespread tendency to spiritualize such emerging technologies as the photograph, the telegraph, and electromagnetism. Today, many of our own emerging sciences, from Artificial Intelligence to the study of dark matter to the renewed attention to the therapeutic properties of psilocybin, again demonstrate that the line between science and “pseudo science” can be difficult to draw.

Eleanor Heartney, “Across the U.S., Museums Are Exploring Spiritualism and the Occult as Powerful, Unsung Forces in Art History”, February 21 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/spiritualism-and-art-2072067

It is unclear how Heartney believes that AI and “pseudo science” are linked—and since elsewhere she implies that spiritualism is a positive force, it is confusing that she invokes the derogatory “pseudo science” in reference to emerging sciences and Artificial Intelligence in particular. But her quote is provocative, prompting thought about possible links between spiritual beliefs—or pseudoscience, if you wish—and AI.

Instead of seeing our current AIs as useless plagiarists incapable of producing contributions to knowledge, it might be more productive to think of them as modern day Ouija boards, accessing not so much the spiritual realm but the collective unconscious as embodied in massive data sets created by humans past and present. The practice of prompt engineering thus becomes a matter of scrying the unknown or, alternatively, as a surrealist project employing AI as a form of automatism, letting the results provided by the random seeds employed by AIs guide one toward an unknown destination.

If, after years of always being around the corner, AI has recently started to develop at breakneck speed, “Artificial Intelligence” remains a marketing slogan, with the prospect of true Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), capable of actual thought, still in the unknown future. Now many of the current crop of “AIs” are being built by companies that also hope to build precursors to real AGI—for example, OpenAI, which operates both ChatGPT and Dall-E 2, actively seeks to build a “safe and beneficial” AGI—but it is as yet entirely unclear if the current “AIs” represent substantial progress—even though it seems to me that ChatGPT could pass a Turing Test—or are just first steps toward a far distant future.

Still, many AI researchers and futurists believe that an AGI will lead to “the Singularity,” a hypothetical future point reached when artificial general intelligence surpasses human intelligence, leading to rapid technological growth and potentially major changes to human civilization that are as yet, completely unpredictable, much like the behavior of time and space at the center of a black hole (known as a singularity). The Singularity is, ultimately, however not only a philosophical concept, but also a theological one, heir to the apocalyptic properties of the Christian notion of the Rapture. As they re-enchant our world, then, the Witching Cats of New Jersey remind us that there are ghosts in our machines and that our house pets have claws, teeth, and perhaps even dark powers.