Today marks the start of the tenth year of Network City. This may be my favorite course.

Network City

Avery 115, Tuesdays 11-1

“Cities are communications systems.” – Ronald Abler

This course fulfills the Urban Society M.Arch distributional requirement.

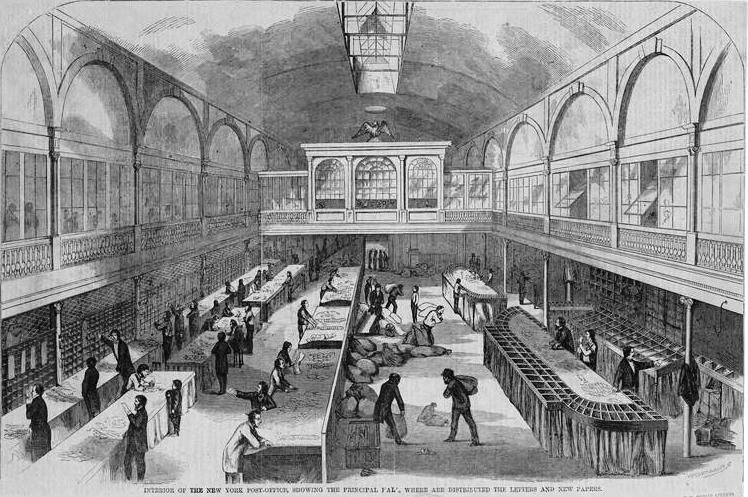

Network City explores how urban areas have developed as ecosystems of competing networks since the late nineteenth century.

Networks of capital, transportation infrastructures, and telecommunications systems centralize cities while dispersing them into larger posturban fields such as the Northeastern seaboard or Southern California. Linked together through networks, today such cities form the core of global capital, producing the geography of flows that structures economies and societies today.

Networks, infrastructures, and property values are the products of historical development. To this end, the first half of the course surveys the development of urbanization since the emergence of the modern network city in the late nineteenth century while the second half focuses on conditions in contemporary urbanism.

A fundamental thesis of the course is that buildings too, function as networks. We will consider the demands of cities and economies together with technological and social networks on program, envelope, and plan, particularly in the office building, the site of consumption, and the individual dwelling unit. In addition we will look at the fraught relationship between signature architecture (the so-called Bilbao-effect) and the contemporary city.

Throughout the course, we will explore the growth of both city and suburbia (and more recently postsuburbia and exurbia) not as separate and opposed phenomena but rather as intrinsically related. Although the material in the course is applicable globally, our focus will be on the development of the American city, in particular, New York, Chicago, Boston, and Los Angeles.

Each class will juxtapose classic readings by sociologists, urban planners, and architects with more contemporary material. Readings will be available online.

Project

The term project will be one chapter within a research book, exploring one architectural, infrastructural, or urbanistic component of the Network City.

Material should not be formulated into a traditional research paper, but rather assembled as a dossier of information that tells a story through the designed and composed sequence of images and texts lead by an analytical narrative you have written yourself.

Design is integral to the term project. All work is to be carefully proofread and fact checked.

Citations are required, using the Chicago humanities footnote method. Please ensure that all images are properly credited.

The book will be designed simultaneously as a printed, bound object and for the Netlab web site. A layout grid will be provided.

A Brief Bibliography of Books regarding Design and Presentation

Kimberley Elam, Grid Systems: Principles of Organizing Type (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004).

Allen Hurlburt, The Grid: A Modular System for the Design and Production of Newspapers, Magazines, and Books (New York: Van Norstand Reinhold, 1978).

Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth. The Planetary Emergence of Global Warming and What We Can Do About It (New York: Rodale, 2006).

Enric Jardí, Twenty-Tips on Typography (Barcelona: ACTAR, 2007).

Josef Muller-Brockmann, Grid Systems in Graphic Design (Zurich: Niggli, 2001)

Timothy Samar, Making and Breaking the Grid. A Graphic Design Layout Workshop (Beverly, MA: Rockport, 2002).

Tomato, Bareback: A Tomato Project (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press,1999).

Discussions on Networked Publics

Students are asked to attend the Discussions on Networked Publics series, taking place this semester at Columbia’s Studio-X on February 9, March 25, April 13, and May 4.

These panels examine how the social and cultural shifts centering around new technologies have transformed our relationships to (and definitions of) place, culture, politics, and infrastructure. Our goal will be to come to an understanding of the changes in culture and society and how architects, designers, historians, and critics might work through this milieu.

* denotes classic reading that demands special attention.

1 1.19 | Introduction: Towards Network City |

2 1.26 | The First Network Cities * Ronald F. Abler “What Makes Cities Important,” Bell Telephone Magazine, March/April. (1970), 10-15. Robert M. Fogelson, “The Business District: Downtown in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Downtown: Its Rise and Fall, 1880-1950, (New Haven: Yale, 2001), 9-42. Anne Querrien, “The Metropolis and the Capital,” Zone 1/2 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 219-221 |

3 2.02 | The Metropolitan Subject * Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. David Levine, ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 324-339. * Ernest W. Burgess, “The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project,” The City: Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment, ed.Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925), 47-62. * Louis Wirth, “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” In American Journal of Sociology 44, July 1938, 1-24. * Michel Foucault, “Docile Bodies,” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 135-156. Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992), 73-77. |

4 2.09 | Office Building as Corporate Machine Special Presentation by Michael Kubo, MIT on the RAND Corporation * William H. Whyte, “Introduction” and “A Generation of Bureaucrats,” The Organization Man, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 3-13 and 63-78. * Norbert Wiener, “What is Cybernetics?” The Human Use of Human Beings (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), 1-19. * John D. Williams, “Comments on the RAND Building Program,” memorandum to RAND Staff, December 26, 1960 (RAND M-4251). Abalos and Herreros, “The Evolution of Space Planning in the Workplace.”Tower and Office: From Modernist Theory to Contemporary Practice (Cambridge: Buell Center/Columbia Book of Architecture/The MIT Press, 2005),177-196. (first half of chapter) Reinhold Martin, “The Physiognomy of the Office,” The Organizational Complex, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2003), 80-105, 114-121. |

8 3.09 | The Return of the Center * Jane Jacobs, “Introduction,” The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1961), 2-25. * Rem Koolhaas, “’Life in the Metropolis’ or ‘The Culture of Congestion,’” Architectural Design 47 (August 1977), 319-325. * Sharon Zukin, “Living Lofts as Terrain and Market” and “The Creation of a ‘Loft Lifestyle” in Loft Living (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1982), 1-22, 58-81. Richard Florida, “The Transformation of Everyday Life” and “The Creative Class,’ in The Rise of the Creative Class (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 1–17, 67–82. David Harvey, “The Constructing of Consent,” A Brief History of Neo-Liberalism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), 39-63. Optional: Bert Mulder, “The Creative City or Redesigning Society,” and Justin O’Connor, “Popular Culture, Reflexivity and Urban Change in Jan Verwijnen and Panu Lehtovuori, eds, Creative Cities. Cultural Industries, Urban Development and the Information Society, (Helsinki: UIAH Publications, 1999), 60-75, 76-100. Dan Graham, “Gordon Matta-Clark” in Gordon Matta-Clark (Marseilles: Musées de Marseilles, 1993), 378-380. |

9 3.16 | Spring Recess |

10 3.23 | The Global City and the New Centrality * Saskia Sassen, “On Concentration and Centrality in the Global City,” Paul L. Knox and Peter J. Taylor, eds., World Cities in a World-System (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 63-78. * Ignasi Sola-Morales, “Terrain Vague”, in Anyplace (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 118-123. * Castells “The Space of Flows,” The Rise of the Network Society, 407-459. Sze Tsung Leong, “Readings of the Attenuated Landscape,” Michael Bell and Sze Tsung Leong, eds., Slow Space (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1998), 186-213. Optional: Martin Pawley, “From Postmodernism to Terrorism,” Terminal Architecture, 132-154. |

11 3.30 | The Clustered Field: Postsuburbia to Edgeless Cities and Beyond * Robert Fishman, “Beyond Suburbia: The Rise of the Technoburb,” Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (New York: Basic Books, 1987), 182-208. Rob Kling, Spencer Olin, and Mark Poster, “Beyond the Edge: The Dynamism of Postsuburban Regions,” and “The Emergence of Postsuburbia: An Introduction,” Rob Kling, Spencer Olin, and Mark Poster, eds. Postsuburban California: The Transformation of Orange County (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), vii-xx, 1-30. Selections from Michael J. Weiss, The Clustered World: How We Live, What We Buy, and What it All Means About Who We Are (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1999). Robert E. Lang and Jennifer LeFurgy, “Edgeless Cities: Examining the Noncentered Metropolis,” Housing Policy Debate 14 (2003): 427-460. |

12 4.06 | The Tourist City * Robert D. Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6 (1995): 65-78 * Melvin M. Weber, “Order in Diversity: Community Without Propinquity,” Cities and Space: The Future of Urban Land, ed. Lowden Wingo, Jr. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1963), 23. Wolfgang Scheppe, Migropolis :Venice / Atlas of a Global Situation (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2009), excerpts. Paul Goldberger, “The Malling of Manhattan.” Metropolis (March 2001), [134]-139, 179.- Bill Bishop, “The Power of Place,” The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 19-80. |

13 4.13 | Conclusion Kazys Varnelis, “The Centripetal City: Telecommunications, the Internet, and the Shaping of the Modern Urban Environment,” Cabinet Magazine 17. Mitchell L. Moss and Anthony M. Townsend, “How Telecommunications Systems are Transforming Urban Spaces,” James O. Wheeler, Yuko Aoyama, and Barney Warf, eds., Cities in the Telecommunications Age: The Fracturing of Geographies (New York: Routledge, 2000), 31-41. |

| |

Read more