What of art in this plague year? With our isolation compounded by unprecedented political polarization, is there any hope of exploring the commonality of shared experience through art? As many of us head into our lockdown again, we are all too aware that the implementation of “social distancing” has produced a transformation in our society, unprecedented within our lifetimes; how might art reflect on such processes?

Consider the term “social distancing.” This peculiar phrase is currently being used to refer to physical separation between individuals in order to reduce exposure to viruses, but prior to this year it had a long history in sociology, referring to social separation among individuals and groups. Like many sociological concepts, social distancing originates with the foundational writings of sociologist Georg Simmel. In his 1903 “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” Simmel describes the growing distance between individuals as a consequence of modernization and the spatial condition of the city:

This mental attitude of metropolitans toward one another we may designate, from a formal point of view, as reserve. If so many inner reactions were responses to the continuous external contacts with innumerable people as are those in the small town, where one knows almost everybody one meets and where one has a positive relation to almost everyone, one would be completely atomized internally and come to an unimaginable psychic state.

Social distance, then, develops when physical distance is not possible and serves as a means of protecting the psyche. Nor is it done alone. On the contrary, social distance is frequently experienced communally: modern individuals flock with others of their kind and, in doing so, experience distance from those outside the group, those that they perceive as unlike themselves. For Simmel, the stranger is both near and far from us: close enough to provoke anxiety yet isolated and therefore unknown. Hence, this sociological explanation would lead us to understand racism as a product of social distance. Racism, it follows, is not so much a prejudiced encounter with individuals at distant remove, but rather a violent misperception of individuals in close proximity. The increasing polarization of American politics between the “woke folx” and the “deplorables” is further evidence of this, with both groups existing as a defense against a dangerous Other while providing a mechanism for reinforcing their member’s shattered identities. With the dominance of contemporary life by social media, the wounded self becomes a reposting machine for social media outrages as a means for the self to affirming its identity and existence through repetition, much as in a liturgical response. But being based entirely on the external threat of an Othered group, the result is a malfunction of social distance as psychic defense. Not only does political discourse grind to a halt, the self fails to develop as an individual. Facing increasing reliance on social media for human connection leads us toward a feedback loop of dopaminergic rewards for positive social stimuli and, like a chimpanzee in a lab cage punching buttons for cocaine-laced biscuits, we are led closer toward the “unimaginable psychic state” of the completely atomized dividual.

This sociological concept of social distance initially appears quite different from pandemic quarantine. And yet, it’s no coincidence that political and racial tensions have risen to a fifty-year high in the United States: the social distancing of quarantine and the social distancing of the modern city share similarities. The chance encounters of the street, the park, and the pub have largely ended. Endless Zoom meetings with one’s co-workers or classmates reinforces positions in class structures. Reading the news about groups that egregiously flaunt restrictions angers us and sets us against them. Our isolation leads us to become more addicted to social media and as social media algorithms highlight our posts to those people who “liked” our previous posts, we condition ourselves to the rush of “likes,” of feedback from those people who already give us feedback——creating a false sense of belonging and an experience of growing distance from those unlike ourselves. So, then, back to the original question I posed: is there any hope of exploring the commonality of shared experience through art?

Early telematic art offers a direction for us. Forty years ago Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, working as the Mobile Image group, created a series of projects entitled “Aesthetic Research in Telecommunications,” both anticipating and surpassing the videoconferencing that has come to be identified with life under quarantine. In Satellite Arts: A Space With No Boundaries (1977), they connected dancers located three thousand miles apart via low-latency satellite links. Although at times the dancers interacted on split screens, as we might see friends interacting on Zoom or Facetime, Galloway and Rabinowitz also composited them together on the screen visible to the audience, thereby creating a third, virtual space. In Hole in Space (1980), they created wormholes to bring together people from opposite coasts. Unlike our screen-based videoconferencing, Hole in Space employed life-size screens displayed in public spaces (Los Angeles’s Century City Shopping Center and New York’s Lincoln Center respectively). Deliberately unadvertised, Hole in Space was as they put it, “a social situation with no rules,” a new condition that, as a documentary of the work shows, was profoundly moving to the people who participated. In a third project, the Electronic Cafe of 1984, they connected five restaurants—in Korean, Hispanic, African-American, and beach communities—with video equipment and drawing tablets so that individuals in one venue (including artists-in-residence) could exchange ideas and images with unknown individuals in another. Throughout, Galloway and Rabinowitz approached electronic technology as a means of overcoming both physical distance and the social distance between individuals.

It’s possible to imagine what a new telematic art might look like today, outside of the confines of conventional videoconferencing. For example, already yin 2004, AUDC (myself and Robert Sumrell) proposed creating guerrilla versions of the Hole in Space cartable in a backpack that could be deployed at random throughout a network of cities.

At the time we wrote:

Windows on the World is a formulary for a new urbanism that alleviates boredom with the city and encourages communication in public, rather than private settings. It facilitates open, spontaneous, and democratic exchanges between groups while requiring no special skills to operate. Participants share both their differences and similarities through direct interaction, replacing the myth of global hegemony and projected stereotypes with personal experience.

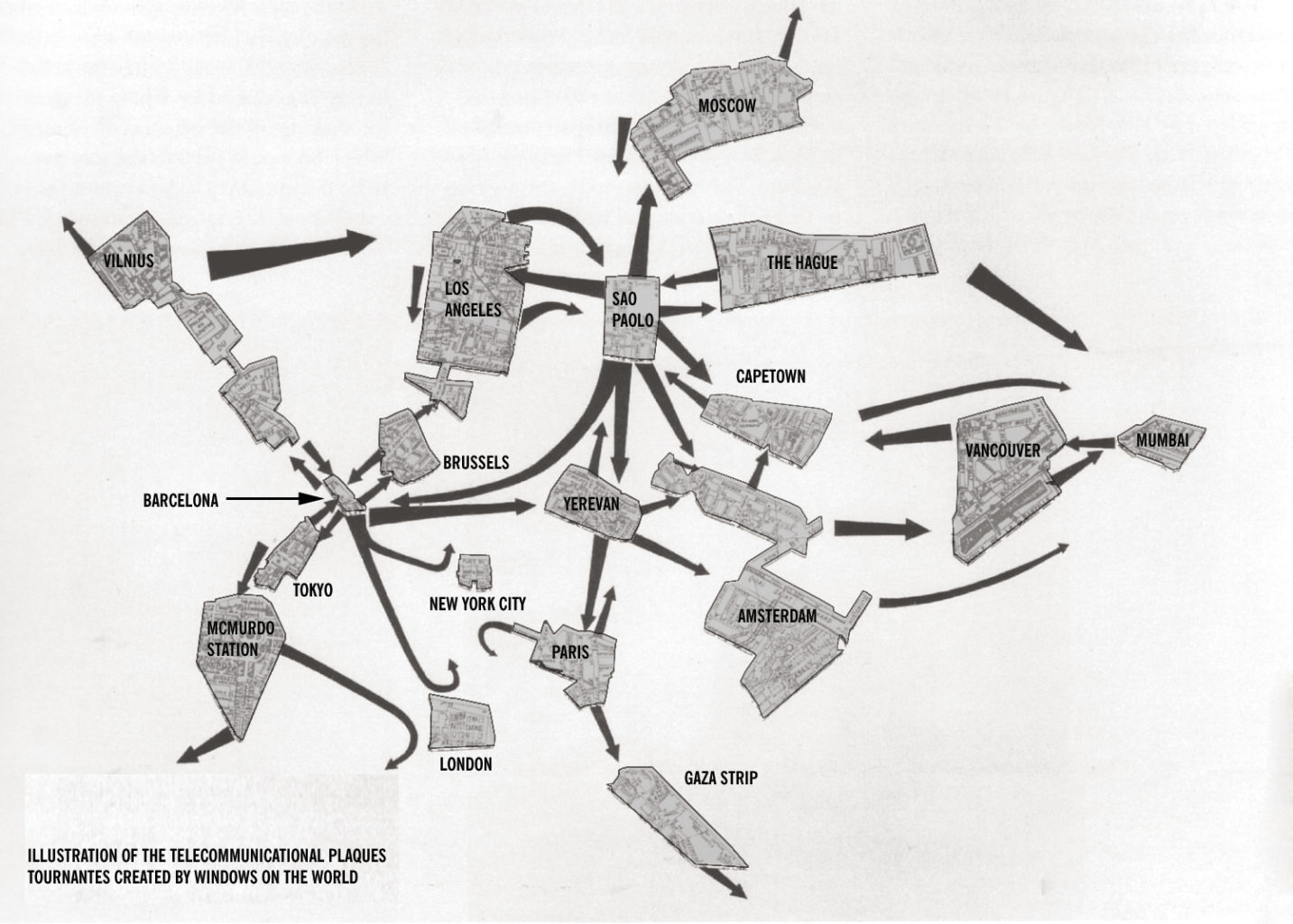

Windows on the World remaps our cities to create a telematic dérive. Guy Debord’s map “the Naked City” is now a map of the world. Each portal becomes what the Situationists called a plaque tournante, a center, a place of exchange, a site where ambiance dominates and planners’ power to control our lives is disrupted. People can wander from portal to portal within their city, experiencing and constructing different situations. Windows on the World changes the experience people have not only of the world, but of their city.

Like the Situationist dérive, Windows on the World operates outside of commerce and planning. There is no advertisement. The project is at its strongest when it is by chance. Some portals are temporary, even hidden. Others are improbable, or not easy to access. In a back alley in Prague, shaded by a Northern exposure, is a portal to a zoo in Sao Paolo. From a dangerous street in the Bronx, a door opens onto the Champs-Elysees. Another portal, in Zurich, looks out onto a busy railroad yard in Rotterdam.

Sixteen years have passed and the widespread adoption of social media during that time has led us to confuse the public and the private. We invite our friends and even strangers into our living rooms and our bedrooms. Formality has fallen away as suit and dress have given way to sweatpants and leggings. But there is no comfort to these forms of sociality or dress. Instead, we understand ourselves to always be on display, to have to perform at all times to receive our dopamine rush both for social interaction and for work, which is ever more subject to bureaucratic projects like “agile frameworks” and “total quality management” offering micro-rewards and micro-punishments for meaningless tasks completed. With this new search for (over) stimulus, there is every chance that a project like Windows on the World will fail as individuals provoke each other like chimps in separate cages at a zoo (or as humans do on Chatroulette). But thinking through how social connections and an appeal to a universal human connection might be made today—however obliquely—is an imperative task for art and technology.

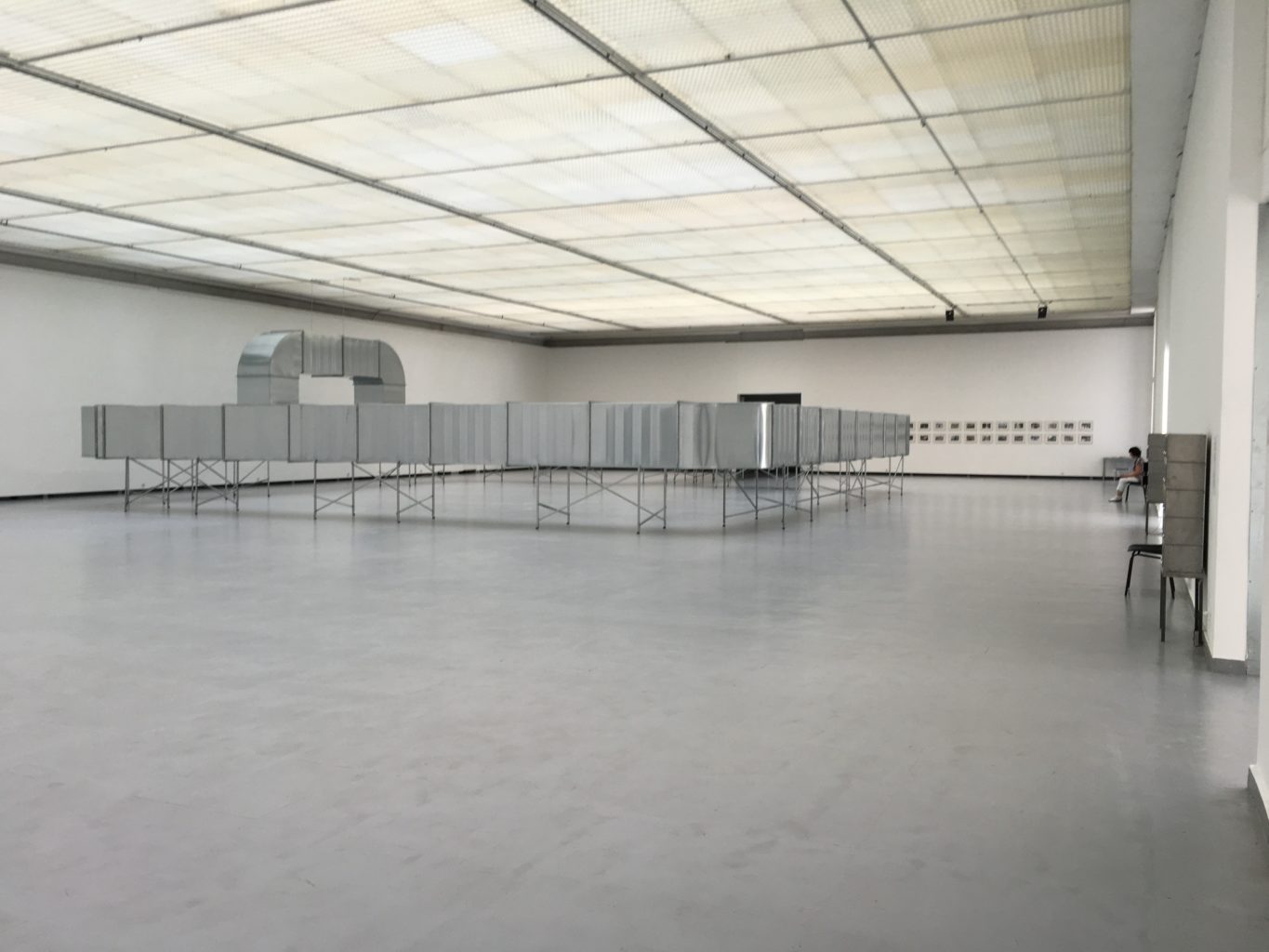

Work in this vein certainly does not always need to provide an affirmative alternative space. Returning to my own work at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2016, the Perkūnas project aims to make us sonically aware of the social distancing produced by network culture. Visually, this structure is both abstract—a simple architectural form—and a harbinger from another world, hence the name Perkūnas [the Lithuanian name for (the God of) Thunder]. Built of large ventilation ducting commonly found (and heard) in art museums and other large public structures, Perkūnas’s role isn’t to condition the air in the environment, rather it is to produce sound in accordance with the number of Wi-Fi enabled devices in the room.

A microprocessor monitors the space for active Wi-Fi-enabled electronic gadgets, increasing or decreasing the amount of air flowing through the duct and hence, the amount of noise in the room based on the number of gadgets. If there are no gadgets present or if everyone’s Wi-Fi is disabled, the duct makes little or no sound. With a couple of gadgets, it make a louder sound. The more gadgets, the more sound. Our ability to communicate verbally is directly affected by the amount of gadgets. If we leave our gadgets behind or turn them off, Perkūnas stays quiet. But people don’t read wall text, they look at their phones, distracted by whatever algorithm is guiding them along their day and Perkūnas howls at them, their distraction drowning out their ability to communicate verbally.

Perkūnas doesn’t bring people together, but it suggests one direction for an art that can speak frankly to us about our social media-obsessed world without resorting to parody or false political promises about participation. Finding new ways for art to negotiate the space between social media and social distancing is a task at hand.