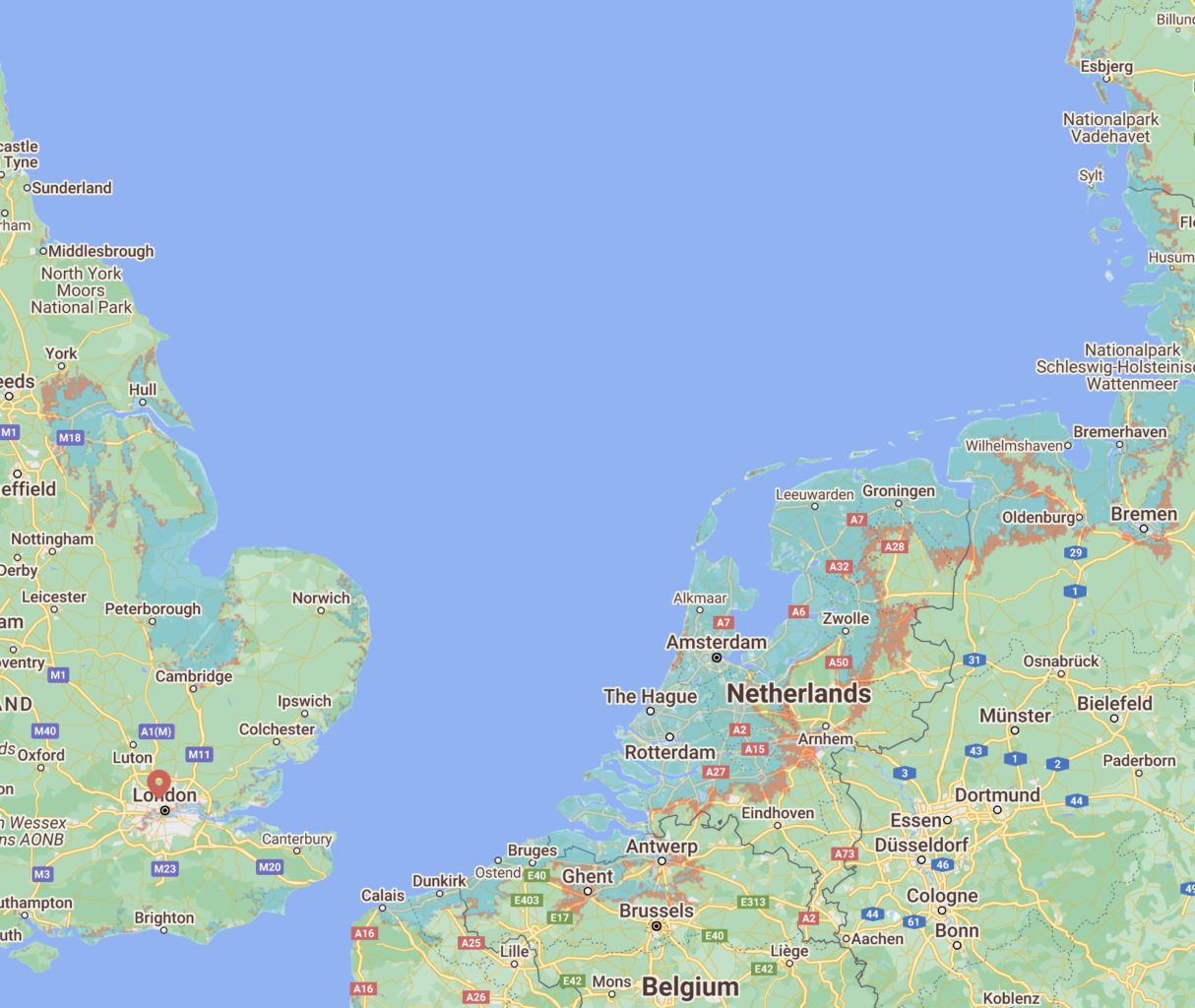

In 1422, the long decline of the Kingdom of Doggerland came to an end with the drowning of the vast island once found in the North Sea between England, Denmark, Norway, and the Low Countries. Roughly 40,000 km2 (15,500 sq mi) in size, for over a thousand years, Doggerland remained a European Kingdom even as rising sea levels led to large areas being abandoned and depopulated in the later Middle Ages.

With the island destroyed by the tsunami (“the Great Drowning”) caused when an earthquake dislodged vast portions of the undersea continental shelf off Norway, the extinguishing of an entire European kingdom was a critical event, perhaps the critical event, in the history of Early Modern Europe, demonstrating the frailty of mere mortals and the insufficiency of human faith against the wrath of nature.

The island was first referred to in the 4th century BC by the Greek geographer Pythaes of Massalia as “the Kingdom of the Fishes,” and would be dubbed “Ictis” by Diodorus Siculus during the 1st century BC:

The inhabitants of that part of Britain which is called Belerion are very fond of strangers and from their intercourse with foreign merchants are civilized in their manner of life. They prepare the tin, working very carefully the earth in which it is produced. The ground is rocky but it contains earthy veins, the produce of which is ground down, smelted and purified. They beat the metal into masses shaped like knuckle-bones and carry it off to a certain island off Britain called Iktis. During the ebb of the tide the intervening space is left dry and they carry over to the island the tin in abundance in their wagons … Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhone.

Pliny referred to Doggerland as “Mictis,” describing it as “lying inwards six days’ sail from Britain, where tin is found, and to which the Britons cross in boats of wickerwork covered with stitched hides.” A century later, Doggerland became the northernmost land conquered by Caesar during the Gallic Wars of 54 and 55AD and remained under Roman rule until the Attacotti tribes threw out the Romans in the Dogger Risings of the 364-365 and, in 367, crossed the Dogger Channel to Britain to participate in the widespread risings called the Great Conspiracy.

British Museum.

In the early 10th century, the semi-legendary Harthacnut I became the first King of both Denmark and Fiskeland (Doggerland). Cnut the Great (c. 990-1035) united Denmark and Fiskeland with England and Norway in the brief but effective North Sea Empire. Even so, the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, which began in 950 and lasted until 1250, wreaked havoc with Fiskeland as water levels rose and some of the more low-lying farmland and the fish farms (vivaria) that the Fiske peoples had pioneered were inundated.

No matter how mighty he was in politics and war, Cnut himself understood the futility of the rising of the waters (the Stigendevand) and, as Henry of Huntingdon later recounted in his Historia Anglorum:

When he was at the height of his ascendancy, he ordered his chair to be placed on the sea-shore as the tide was coming in. Then he said to the rising tide, “You are subject to me, as the land on which I am sitting is mine, and no one has resisted my overlordship with impunity. I command you, therefore, not to rise on to my land, nor to presume to wet the clothing or limbs of your master.” But the sea came up as usual, and disrespectfully drenched the king’s feet and shins. So jumping back, the king cried, “Let all the world know that the power of kings is empty and worthless, and there is no king worthy of the name save Him by whose will heaven, earth and the sea obey eternal laws.”

Inhabitants slowly began to drift away, to Britain, Denmark and Norway, but also Iceland, Greenland, and other points west. By the thirteenth century, the country was dominated by a court whose strength was primarily nautical—the powerful Dogger ships that controlled the North Sea—and by the monastic orders that alternately served, and competed with, the court. Although Doggerland (the new common name of the country after 1360) had been largely spared the Plague, by the time of Cnut VI, also known as Saint Cnut the Drowned (1394-1422), the stigendevand had become acute and a sizable portion of the remaining population inhabited floating vessels at all times.

Still, Doggerland’s Court was widely known for its accomplishments in art, music, and literature. Clockworks and complicated mechanisms were a noted specialty. With the end of Doggerland long prophesied, time-keeping had been an obsession in Doggerland—a common Doggerish saying is “Hours are a greater treasure than gold”—and spring driven clocks were developed in the first years of the fourteenth century. The precursor to the piano—the clavichord—was invented in Doggerland in the early 14th century and primitive forms of printing with carved plates had begun to be employed.

On 21 April 1422, Ugo, Abbot of Drounen wrote,

Late in the morning, when the markets were full, a shudder came upon the land and the sea retreated. The waves rolled back over the horizon and the Dogger ships were left on dry land, revealing monstrous creatures that normally dwelt under the water. The good monks of the Abbey prayed for salvation from this horror, but to no avail as the sea came rushing back and we were forced to climb into the row boats I had commanded the monks to build in the case of the Flood, which God had now thrust upon us again. Thousands were swept past us and those we could haul aboard were saved, but most were drowned under the waves. To our dismay, we saw the King sitting on the rocks but the waves rose and covered him.

The exodus from Doggerland led to an influx of refugees to the continent precisely at a point in which post-plague Europe itself lay in wait for a stimulus that would trigger the Renaissance. Although chiefly seen today as a Flemish painter, Jan van Eyck was Doggerish and brought the previously closely-held secrets of oil painting to the rest of Europe while Rogier van der Weyden apprenticed there in his youth. Exiled scholars helped found the Universitas Lovaniensis (Old University of Leuven) while other experts in Latin, astronomy, alchemy, and the culinary sciences became teachers throughout Europe. For example, Henry of Drouen, a tutor for Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici. Francesco Colonna was the son of Dogger refugees in Venice—a natural destination for many—and in his famed Hypnerotomachia Poliphili conjures a dreamscape that scholars see as a description of his parents’ lost homeland.

The first extant spring-wound clock wound up in the court of Burgundy after the Drowning. As is well known by now, Johannes Gutenberg worked with survivors from Doggerland to develop the printing press, a fact that the famed printer Aldus Manutius would memorialize in his logo for the Aldine press.

Laments for Doggerland were common in the Low Countries for centuries after. The Drowning of Doggerland or “de Doyer Overstroming” was a cautionary tale memorialized and returned to again and again by poets, painters, and musicians. A pastoral land of sheep and fish that escaped the ravages of Plague and war but was lost forever due to the vengeance of the sea could hardly be far from the imagination of the creative mind. In the late 17th century, in particular, there was a revival of interest in the Dogger pastoral as Flemish artists rejected the excesses of the Spanish Baroque and their wealthy mercantilist clients sought to surrounded themselves with visible reminders of their—often imagined—past as descendants of the Court of Doggerland.

Such laments would dissipate over the course of the eighteenth century as a modernizing Europe increasingly abandoned the lost pastoral land for a eudaemonic narrative of growth and newfound wealth. With the colonization of North America by Europeans, a new and much larger land was—they thought—given to them by God to replace the lost land under the sea. In particular, early settlers to Newfoundland initially called it “New Dagger Land” or “Nieuwe Doyer Land” and Governor William de Doyer had pronounced “It a free land, to be inhabited by all brothers of the land beneath the sea, be they English, French, or Dutch,” a dream wiped out after his death in a storm at sea in 1686 and the subsequent events of King William’s War (1688-1697) even though the ideal was referred to, somewhat cynically, during the British development of the Canadian colonies after the seizure of New France less than a century later.

Credit:Climate Central

For us, the drowning of Doggerland has a different meaning. Rather than a lost past to lament, it is a cautionary tale of the Anthropocene near future. The impact of climate change on the environment forces us to consider that rising seas will likely drown substantial areas of the world, including the coasts of Denmark, eastern Britain, Belgium, and much of the Netherlands (and of course, much, much more of the world). Unlike the inhabitants of Doggerland, we have a choice, but will we take it?