The other day, I posted some AI images of land art that doesn’t exist on Instagram. I didn’t have a plan for these, but I liked them and wanted to share them. In the comments, my friend the photographer Richard Barnes wrote, “This is our new world which for the moment is totally reliant on the old one.”

Richard is absolutely right and there is a lot to unpack in that sentence. To take one obvious reading, AI image generation is based on datasets of images on the Internet. You can read my extensive take on this in my last essay for this site, California Forever, Or the Aesthetics of AI Images, but today, I want to tackle the issue of AI imagery and originality.

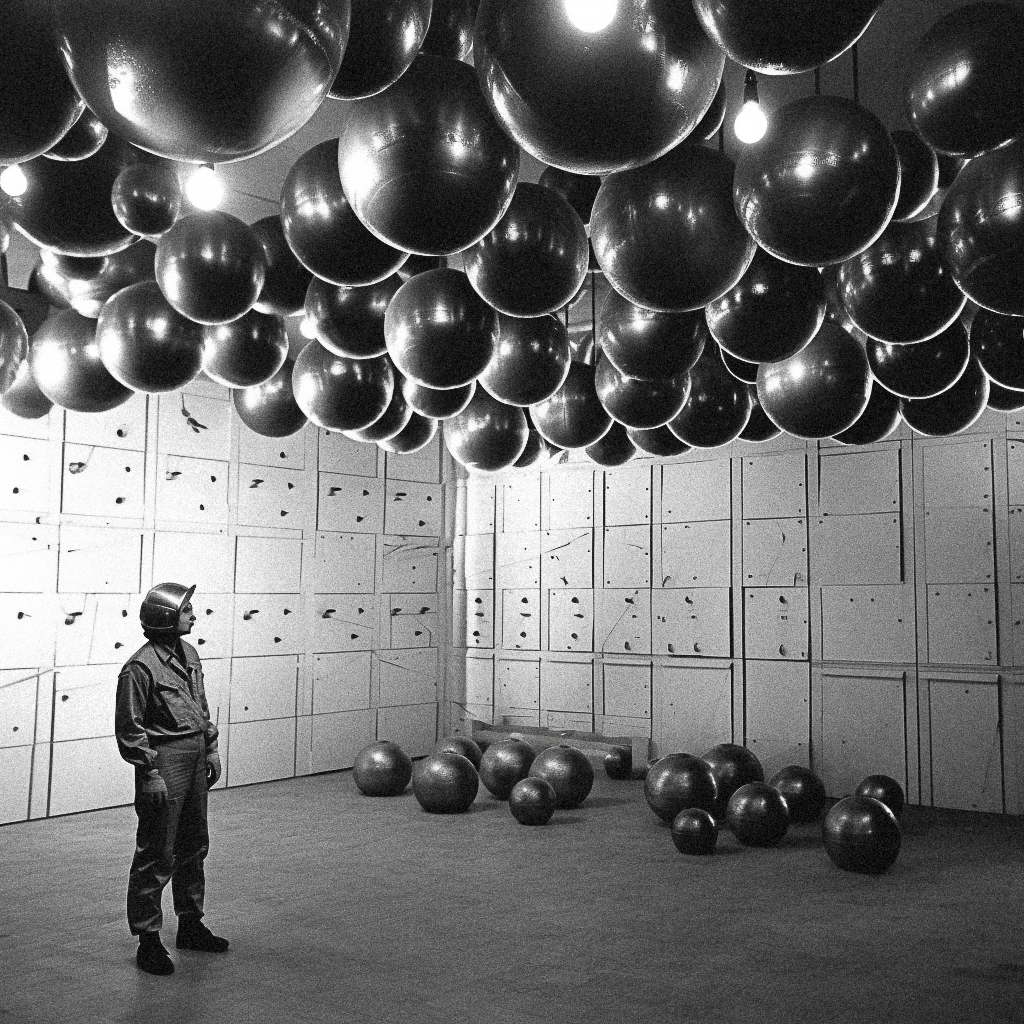

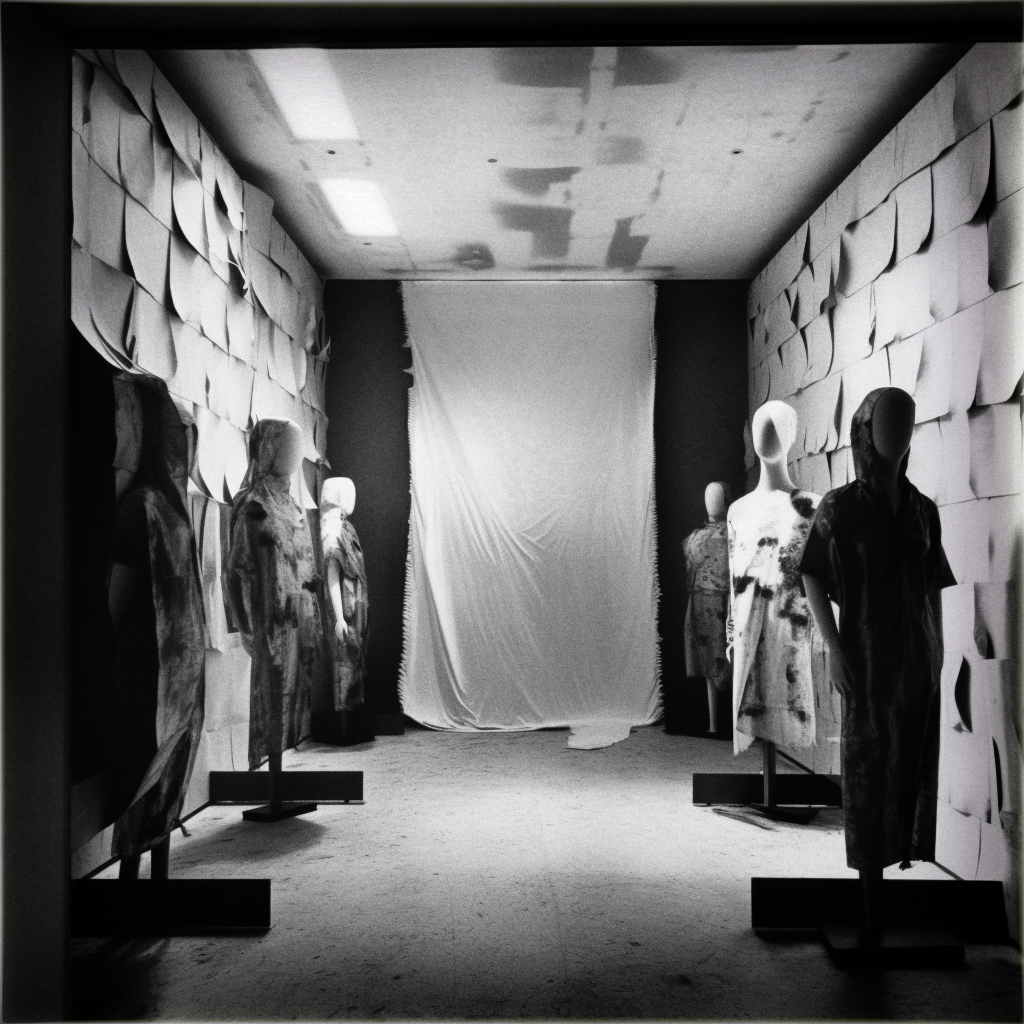

My desire to make these images was backward-looking, or more properly, hauntological. Hauntology, a concept that emerged from the work of French philosopher Jacques Derrida, later popularized in cultural theory by Mark Fisher, suggests that the present is haunted by the unfulfilled potentialities of the past, creating a sense of nostalgia for lost futures that were never realized. Fisher writes: “What haunts the digital cul-de-sacs of the twenty-first century is not so much the past as all the lost futures that the twentieth century taught us to anticipate.” (Mark Fisher, “What is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 1 (Fall 2012), 16, article paywalled by JSTOR). For Fisher, much of recent culture is permeated by this hauntological quality, exploring historical references, styles, and ideas that never fully materialized in their own time.

If this concept is unfamiliar, then take the show Stranger Things. Set in the 1980s, not only does it explore the aesthetic and cultural motifs of that era, it revisits the past in ways that underscore the absence of the utopian visions once promised by that time. This is evident in the show’s theme song by Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon (a.k.a. S U R V I V E), informed by 1980s synthesizer music by musicians like Tangerine Dream, Giorgio Moroder, Jean-Michel Jarré, Vangelis, and John Carpenter and performed on modular synthesizers and vintage synthesizers from the 1970s. Through its retrofuturistic setting, supernatural elements, and cultural references, Stranger Things effectively embodies this hauntological sentiment, appealing to audiences by conjuring a collective memory of a past both familiar and lost, a space where the promise of progress and the fear of what lies in the unknown are in constant dialogue, thereby reflecting our contemporary longing for a future that seems increasingly out of reach in the face of technological stagnation and political paralysis. Throughout the series, an alternate dimension called “the Upside Down” functions allegorically as a manifestation of hauntology, representing the shadowy underside of progress and the hidden costs of failed utopias. This parallel dimension, while mirroring the physical world, is engulfed in darkness, decay, and danger, embodying the repressed anxieties not only of teenage sexuality—the familiar foundation of horror films—but also of the pursuit of advancement without ethical consideration. It can be interpreted as the tangible realization of the lost futures Fisher describes, a space where the dreams of the past are not just forgotten but actively twisted into nightmares. This allegorical realm underscores the series’ exploration of the impact of scientific hubris and the disintegration of the social fabric, issues that resonate with contemporary anxieties about technological overreach and the erosion of social bonds. Through the lens of the Upside Down, Stranger Things critiques the nostalgia for a past that never fully addressed these underlying tensions, suggesting that without confronting these spectral fears, they will continue to haunt us, impeding the realization of truly progressive futures.

Being born in 1967, I was in high school in 1983, the year in which the first season of Stranger Things is set, so I would have been older than the kids in Stranger Things, but the showrunners, Matt and Russ Duffer (the Duffer Brothers) were born in 1984. There is something about the era just before one is born and in the years before one forms lasting memories, that triggers the hauntological sense, particularly in regard to its relation to the Freudian uncanny (the unheimlich), which emerges not just as a theoretical concept but as a lived emotional reality, the encounter with something familiar yet estranged by time or context, generating an unsettling yet compelling attraction. The era immediately before one’s birth is fertile ground for the uncanny because it is inherently connected to one’s existence, yet it remains elusive and out of reach, shrouded in the fog of collective cultural memory rather than personal experience.

This is where my interest in Land Art, which thrived in the late 1960s and early 1980s comes from. It’s a mythic and heroic past, right outside the scope of my lived awareness. Land Art, moveover, is at a particular inflection in the Greenbergian history of modern art and one that brings us closer to our topic at hand. Art critic Clement Greenberg famously sought to distill the essence and trajectory of art through the modernist progression of self-criticism towards purity and autonomy, particularly in painting. Greenberg posited that art should focus on the specificity of the medium, leading to an emphasis on formal qualities over content or context. Specifically, Greenberg argued that modernist painters should embrace and explore the flatness of the canvas rather than attempt to deny it through illusionistic techniques that create a sense of three-dimensional space on the two-dimensional surface. He saw abstract expressionism and color field painting as driven by the gradual shedding of extraneous elements (like figurative representation, narrative, and illusionistic depth) that were not essential to painting as a medium. This process of reduction aimed at focusing on what was uniquely intrinsic to painting—its flat surface and the potential for pure color and form. This approach is distinctly indebted to Hegelian aesthetics, in which art is seen as a vehicle for the spirit (Geist) to realize itself, moving towards a form of absolute knowing or self-consciousness. The late 1960s projects of Minimal Art, Land Art, and Conceptual Art can all be seen as elaborations of Greenbergian modernism. Minimal Art, with its emphasis on the physical object and the space it occupies, pushes Greenberg’s interest in medium specificity to its logical extreme by reducing art to its most fundamental geometric forms and materials, thereby focusing on the “objecthood” of the artwork itself. Land Art extends this exploration to the medium of the earth itself, engaging directly with the landscape to highlight the intrinsic qualities of the environment and the artwork’s integration with its site-specific context, thus reflecting Greenberg’s emphasis on the inherent characteristics of the artistic medium. Conceptual Art, although seemingly divergent in its prioritization of idea over form, aligns with Greenbergian modernism by stripping art down to its conceptual essence, thereby challenging the traditional boundaries of the art object and emphasizing the primacy of the idea, akin to Greenberg’s focus on the essential qualities of painting and bringing art back to relevance as a philosophical discourse. Together, these movements expand upon Greenberg’s foundational principles by exploring the boundaries of what art can be, each pushing the dialogue about medium specificity and the pursuit of purity in art further.

Coming out of architecture and history, I find art without rigor frustrating and boring, so the art of the late 1960s and early 1970s is my north star and I am indeed something of a neo-Greenbergian (more on that here). But during the 1970s, the Greenbergian trajectory encountered significant challenges, marking a pivot away from these ideals towards a more fragmented, pluralistic understanding of art. Rosalind Krauss’s 1979 essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” serves as a critical juncture in this shift. Krauss dismantles the Greenbergian barrier between sculpture and not-sculpture by introducing a set of oppositions that allowed for a broader, more inclusive understanding of sculpture. This “expanded field” theory challenged the purity of medium specificity by embracing a wider range of practices and materials, effectively undermining the modernist notion of progressive refinement and autonomy of the arts. Krauss:

From the structure laid out above, it is obvious that the logic of the space of postmodernist practice is no longer organized around the definition of a given medium on the grounds of material, or, for that matter, the perception of material. It is organized instead through the universe of terms that are felt to be in opposition within a cultural situation.

Krauss’s essay, well-intentioned though it was, did not offer a positive direction for research in art, encouraging the sort of lazy pluralism and market-oriented art that has defined far too much art production in the years since.

The one exception to all this, however, is photography. If, in my essay on the aesthetics of AI images, I lamented the obsession with technical proficiency at the cost of taste in amateur HDR photography, in the hands of the best photographers —from the New Topographics movement in the 1970s to the work of great living photographers today, like Hiroshi Sugimoto, Guy Dickinson, David Maisel and Richard Barnes—the technical nature of photography is used to explore the photograph as a medium. And photography, by its very nature as an index of reality, its inexorable relationship between the subject and its representation—aligns with the Greenbergian ideal of art that is true to its medium more effectively than other media.

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October, Vol. 8 (Spring 1979), 43.

Few artists have interrogated the roles of authorship, originality, and representation as effectively as the Pictures Generation, a loosely affiliated group of artists—mainly photographers—named after Pictures, a 1977 exhibition at New York’s Artists Space curated by Douglas Crimp. These artists embraced appropriation, montage, and the recontextualization of pre-existing images, deliberately blurring the boundaries between high art and popular culture and questioning the notion of an artwork’s purity and originality. Not all of this work still speaks to us today. John Baldessari’s art has aged poorly and many artists, such as Richard Prince, have long ago stopped doing interesting work. But at the time Prince, Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo (who admittedly also worked in paintings and charcoal, but in ways akin to the other four in this group), and Sherrie Levine produced compelling and rigorous work during this period. Crimp, on the name “pictures”:

To an ever greater extent our experience is governed by pictures, pictures in newspapers and magazines, on television and in the cinema. Next to these pictures firsthand experience begins to retreat, to seem more and more trivial. While it once seemed that pictures had the function of interpreting reality,it now seems that they have usurped it. It therefore becomes imperative to understand the picture itself, not in order to uncover a lost reality, but to determine how a picture becomes a signifying structure of its own accord. But pictures are characterized by something which, though often remarked, is insufficiently understood: that they are extremely difficult to distinguish at the level of their content, that they are to an extraordinary degree opaque to meaning. The actual event and the fictional event, the benign and the horrific, the mundane and the exotic, the possible and the fantastic: all are fused into the all-embracing similitude of the picture.

Douglas Crimp, Pictures (New York: Artists Space, 1977), 3.

For these artists then, the question of representation itself was fundamental, indeed the proper object for art. Crimp elaborated on this in a thorough revision to this essay, published two years later. This time, Crimp introduces the notion that these works demonstrate a postmodernist break with the modernist tradition:

But if postmodernism is to have theoretical value, it cannot be used merely as another chronological term; rather it must disclose the particular nature of a breach with modernism. It is in this sense that the radically new approach to mediums is important. If it had been characteristic of the formal descriptions of modernist art that they were topographical, that they mapped the surfaces of artworks in order to determine their structures, then it has now become necessary to think of description as a stratigraphic activity. Those processes of quotation, excerptation, framing, and staging that constitute the strategies of the work I have been discussing necessitate uncovering strata of representation.

Douglas Crimp, “Pictures,” October, Vol. 8 (Spring 1979), 87.

The astute reader might note that this is in the very same issue as the Krauss essay above. The issue, however, does not lead with either essay, but by a piece titled “Lecture in Inauguration of the Chair of Literary Semiology, Collège de France, January 7, 1977.” The author is, of course, the semiotician Roland Barthes and he is the crux to the argument of this essay. Barthes’s inaugural lecture at the Collège de France marks the acceptance of semiotics, the study of signs, in the university and sets out an agenda in which the field would not only attempt to analyze linguistic and literary matters but also provide a framework for decoding culture at large. Barthes is especially important to us in terms of his 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” which was published in a widely read 1977 English collection of his works titled Image-Music-Text. In this essay, Barthes challenges traditional notions of authorial sovereignty by arguing that the meaning of a text is not anchored in the author’s original intent but is instead constructed by the reader’s engagement with the text. This radical shift foregrounds the role of the audience in creating meaning, suggesting that a work of art is a collaborative space where interpretations multiply beyond the author’s control. Intertwined with this concept is the idea of intertextuality, which posits that every text (or artwork) is not an isolated entity but a mosaic of references, influences, and echoes from other texts. Intertextuality underscores the interconnectedness of cultural production, indicating that the understanding of any work is contingent upon its relation to the broader network of cultural artifacts. Together, these concepts dismantle the traditional hierarchy between creator and receiver, emphasizing the active role of the reader or viewer in making meaning and highlighting the complex web of relationships that define the production and reception of art.

This perspective was crucial for the Pictures artists who frequently employed appropriation as a strategy, taking pre-existing images from various media and recontextualizing them in their art. This method directly engaged with Barthes’s idea by challenging the original context and intended meaning of these images, thus questioning the notions of originality and authorship. In doing so, they highlighted the idea that the creator’s authority over an artwork’s meaning is not absolute but rather shared with viewers, who bring their own interpretations and experiences to bear on the work.

Moreover, these artists applied Barthes’s concept to emphasize the fluidity and contingency of meaning. Their work often invites viewers to interpret images through their own cultural references and personal experiences, suggesting that meaning is not a fixed entity but a dynamic interaction. In critically engaging with the proliferation of images in contemporary society, the Pictures Generation explored how photographic and cinematic imagery shapes perceptions of identity and reality. This critical stance aligns with Barthes’s view of the text (or image) as a fabric of quotations and influences, further diminishing the role of the author in favor of a more collaborative and interpretive approach to meaning-making.

Crucially, this shift also led to a reevaluation of the artist’s identity. Rather than being seen as the singular source of meaning, artists of the Pictures Generation positioned themselves more as curators or commentators, utilizing the visual languages of their time to critique cultural norms and values. This reflects a move away from the modernist emphasis on the artist’s unique vision toward a recognition of the complex, contextual nature of art-making and interpretation.

Barthes’s idea—that the author’s intent and biography recede in importance compared to the reader’s role in creating meaning—parallels a shift towards viewing the artwork itself, and its reception, as central to its interpretation. This shift can be seen as aligning with Greenberg’s emphasis on the medium’s physical and visual properties as the locus of artistic significance, and Hegel’s idea of art revealing universal truths, though through a more contemporary lens focused on the viewer’s engagement.

But practices such as appropriation, pastiche, and intertextuality can also be framed as a mannerist lament, a response to a widely perceived exhaustion of possibilities within modernism. Compounding this, with the postwar rise of commercial art and Pop art, capital was thoroughly permeated by the strategies of the avant-garde and vice versa. Even shock, the classic technique of the avant–garde had been turned into a marketing tool, signaling the thorough co-option of avant-garde tactics by the very systems it sought to critique. The avant-garde‘s political validity was now deeply in question, something elaborated in the 1984 translation Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde. In this complex landscape, the Pictures Generation’s engagement with the visual language of mass media becomes a double-edged sword: a critique of—and a capitulation to—the pervasive influence of commercial imagery, reflecting a nuanced understanding of the impossibility of purity in an age dominated by reproduction and simulation.

If the Pictures Generation’s engagement already sounds like what Richard Barnes suggested in his comment, “This is our new world which for the moment is totally reliant on the old one” then perhaps this suggests a profitable route to investigate. Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss’s student and Douglas Crimp’s contemporary (as well as my teacher at Cornell for a brilliant year) was a key critic for the Pictures Generation and his 1996 book, The Return of the Real, remains one of the deepest theoretical engagements with art from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s. There, Foster introduces the concept of “Nachträglichkeit,” a term borrowed from Freudian psychoanalysis, often translated into English as “deferred action.”

Nachträglichkeit refers to the way in which events or experiences are reinterpreted and given new meaning in retrospect, influenced by later events or understandings. It suggests that the significance of an artwork or movement is not fixed at the moment of its creation but can be reshaped by subsequent developments in the cultural and theoretical landscape. This recontextualization allows for a continuous reworking of the meaning and relevance of art, as past works are seen through the lens of present concerns and knowledge.

Foster applies this concept to the realm of art history and criticism to argue that the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, for example, can be re-understood and gain new significance in light of later artistic practices and theoretical frameworks:

In Freud an event is registered as traumatic only through a later event that recodes it retroactively, in deferred action. Here I propose that the significance of avant-garde events is produced in an analogous way, through a complex relay of anticipation and reconstruction. Taken together, then, the notions of parallax and deferred action refashion the cliche not only of the neo-avant-garde as merely redundant of the historical avant-garde, but also of the postmodern as only belated in relation to the modern. In so doing I hope that they nuance our accounts of aesthetic shifts and historical breaks as well. Finally, if this model of retroaction can contribute any symbolic resistance to the work of retroversion so pervasive in culture and politics today—that is, the reactionary undoing of the progressive transformations of the century—so much the better.

Hal Foster, The Return of the Real (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996), xii-xiii.

This perspective challenges linear narratives of art history that portray artistic development as a straightforward progression from one style or movement to the next. Instead, Foster emphasizes the recursive nature of artistic innovation, where contemporary artists engage with, reinterpret, and transform the meanings and methodologies of their predecessors. This is where a critical approach to AI imagery that explores the intertextual basis of all art might return to our narrative. In this light, Pictures anticipates a world in which imagery can be freely recombined, in which the role of the author is thoroughly questioned, and the status of the original is thrown into question.

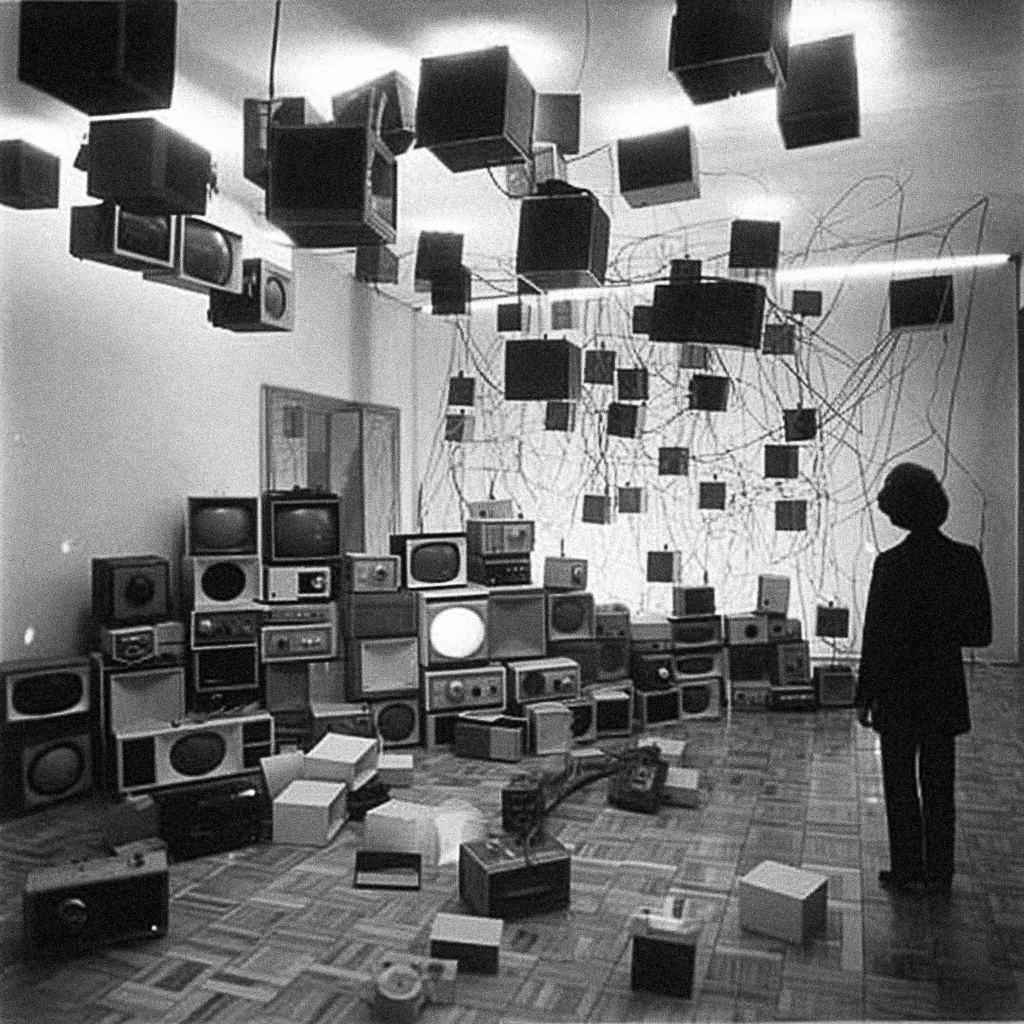

But more than that. Back to Instagram for a moment. Another phenomenon that we have to deal with—that the Pictures Generation did not—is the massive oversaturation of the landscape by user-generated content. This deluge of imagery created by the public—particularly while travelling—has transformed the visual ecosystem, challenging artists to find new methods of engagement and critique. The sheer volume of content complicates efforts to distinguish between the meaningful and the mundane, pushing contemporary artists to navigate and respond to a world where the boundaries between creator and consumer are increasingly blurred. This oversaturation demands a different reevaluation of originality, authenticity, and the role of art in reflecting and shaping societal narratives in the digital age. The are some 35 billion images posted on Instagram every year. These are not just private images, but images that are published in a way previously unimaginable—available to an audience of over a billion users. What does it mean to take a photograph today when the world is already oversaturated? What sense is there of taking a photo of a landscape or a street scene when the same image has been uploaded a thousand times? And what does it mean that serious artists and curators share—by choice or by necessity—work in that same milieu?

Most of the images on Instagram are already AI images. The reason an iPhone or a Pixel can take such an attractive photograph is that they possess highly sophisticated algorithms that create images that appeal to viewers. The iPhone, for instance, utilizes AI-driven features like Smart HDR and Deep Fusion. Smart HDR optimizes the lighting, color, and detail of each subject in a photo, while Deep Fusion merges the best parts of multiple exposures to produce images with superior texture, detail, and reduced noise in low-light conditions. The iPhone’s Neural Engine, part of its Bionic Chip, executes these complex processes, handling up to 600 billion operations per second, to deliver photographs that were unimaginable with traditional digital imaging techniques. Given the insane number of photographs taken at “Instagrammable” sites, and the ecological and social damage that such travel produces, one wonders if something like Bjoern Karmann’s Paragraphica camera might not be a better solution. Using various data points like address, weather, time of day, and nearby places, the Paragraphica then creates a photographic representation using a text-to-image AI generator. This isn’t to say that photography as art is extinct, but it is in peril thanks to oversaturation, which itself is so prolific it has become meaningless.

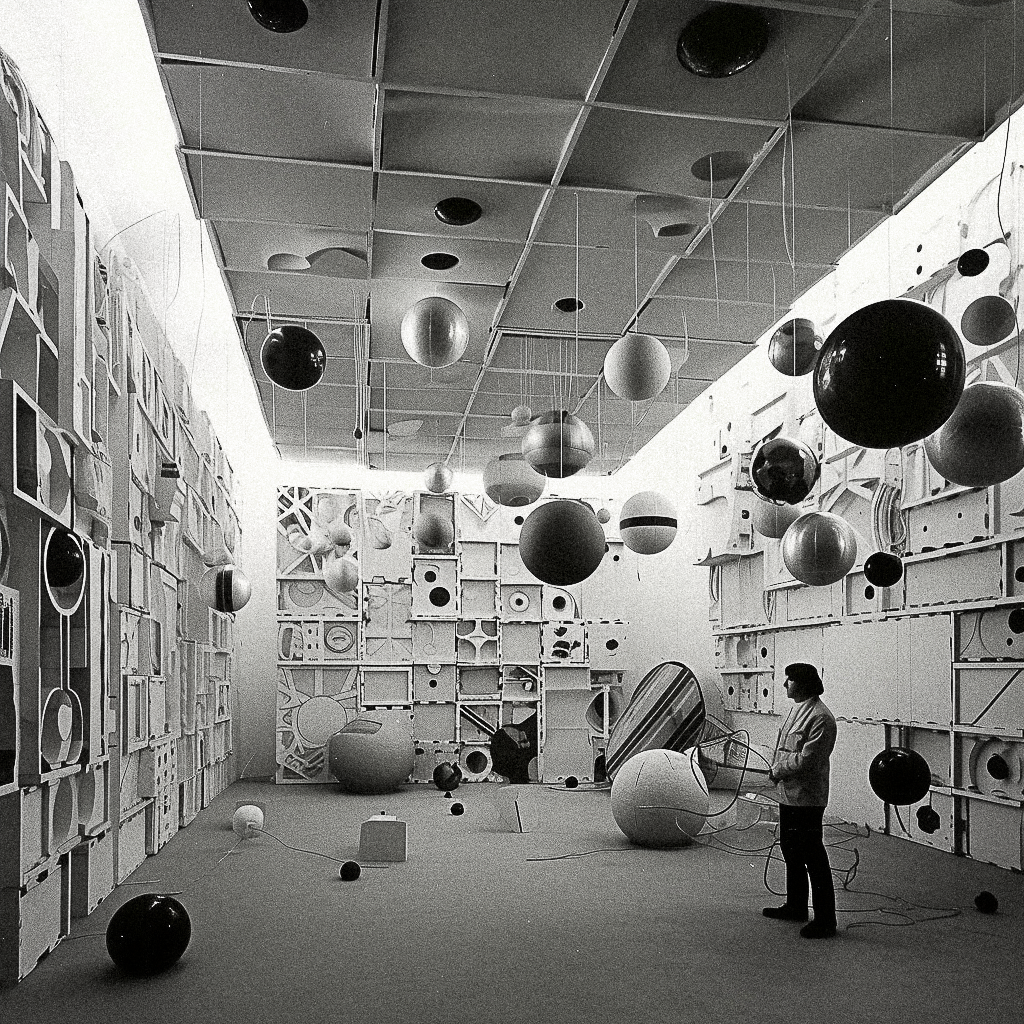

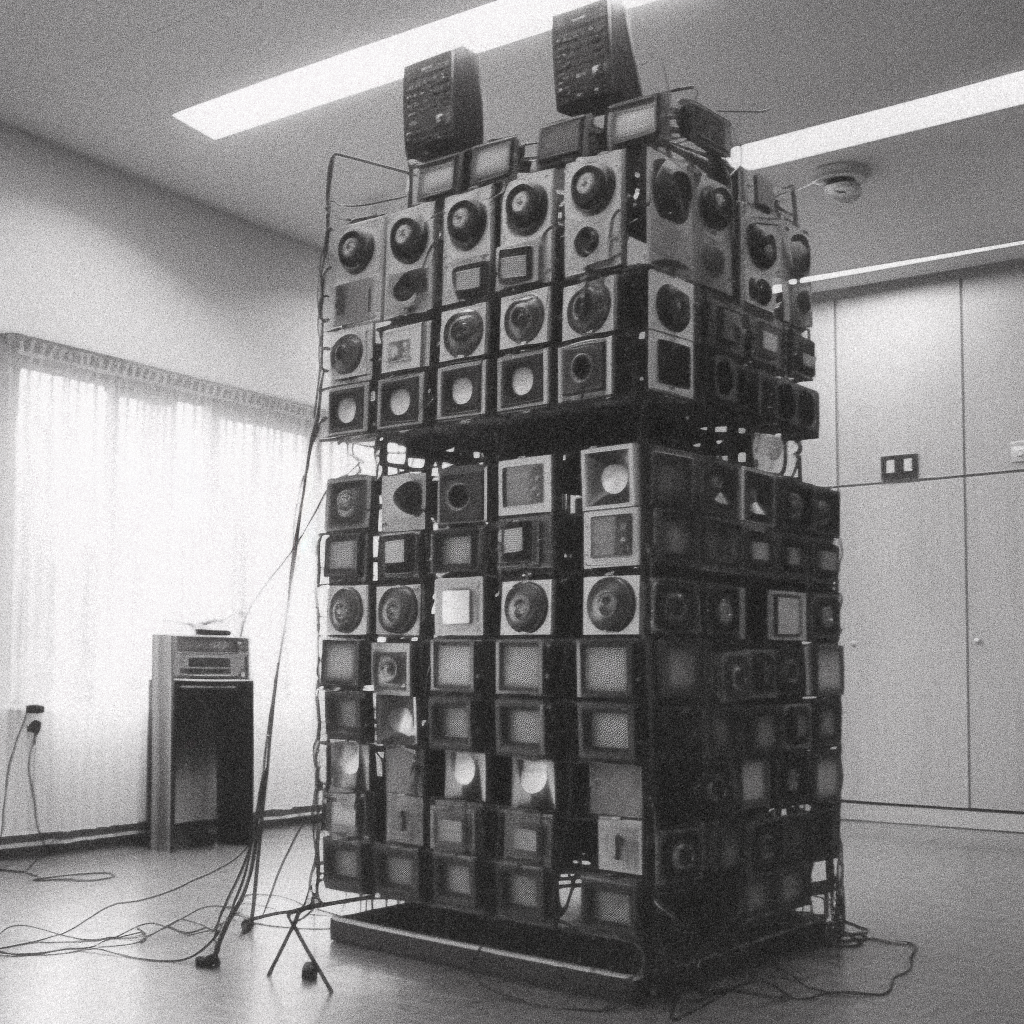

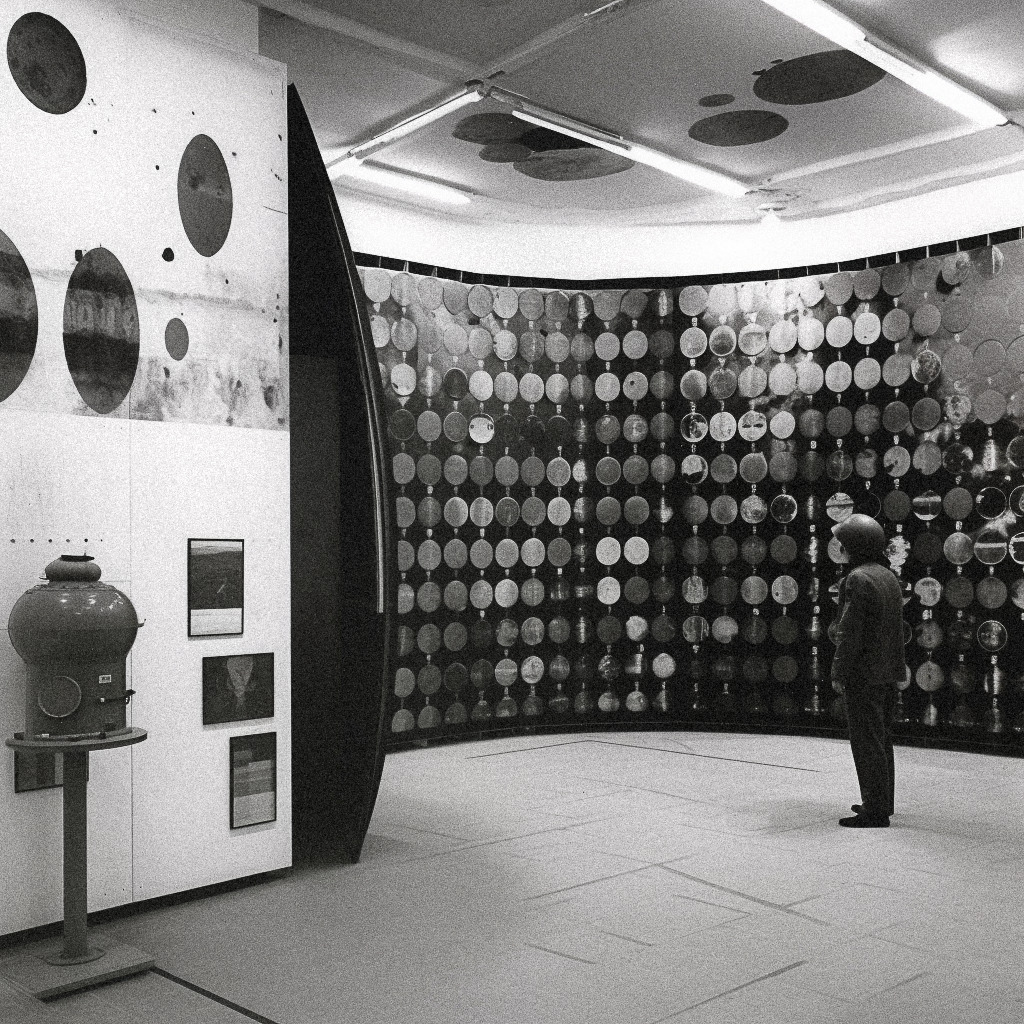

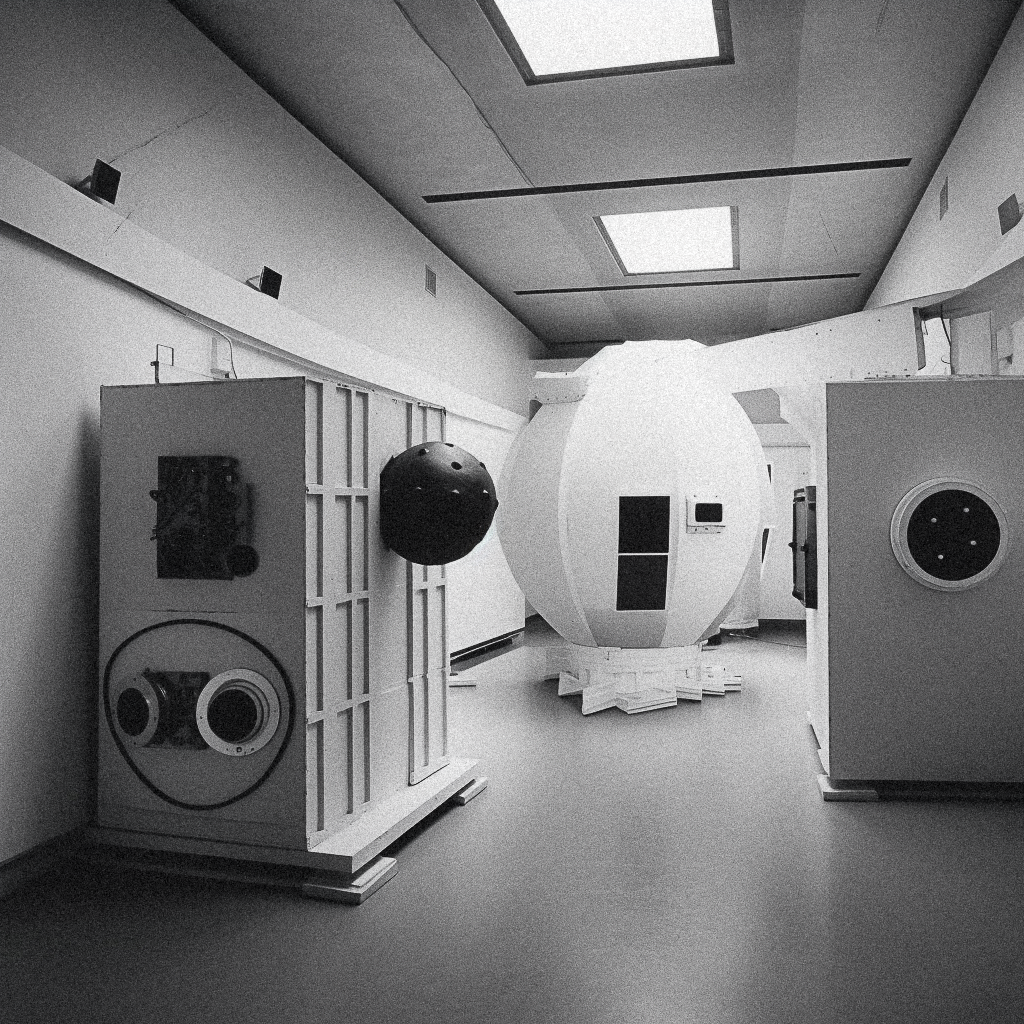

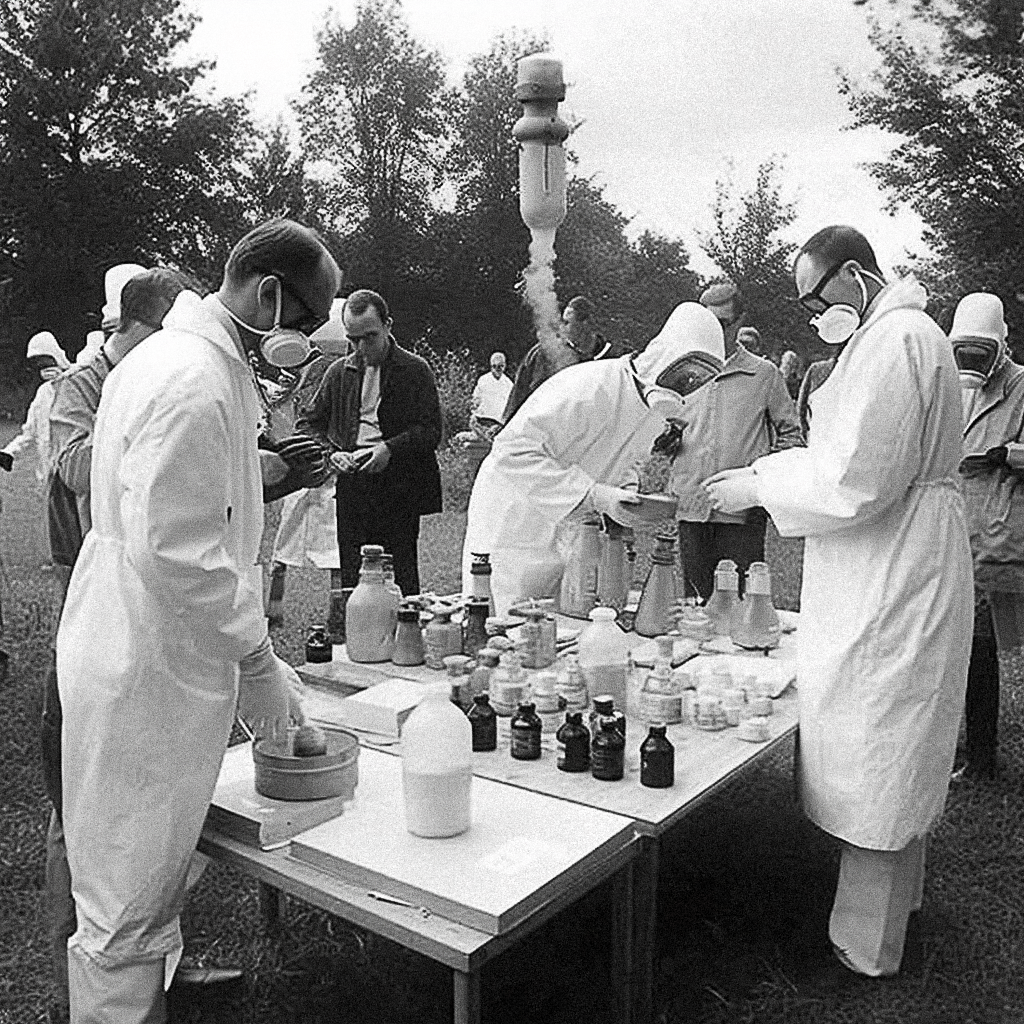

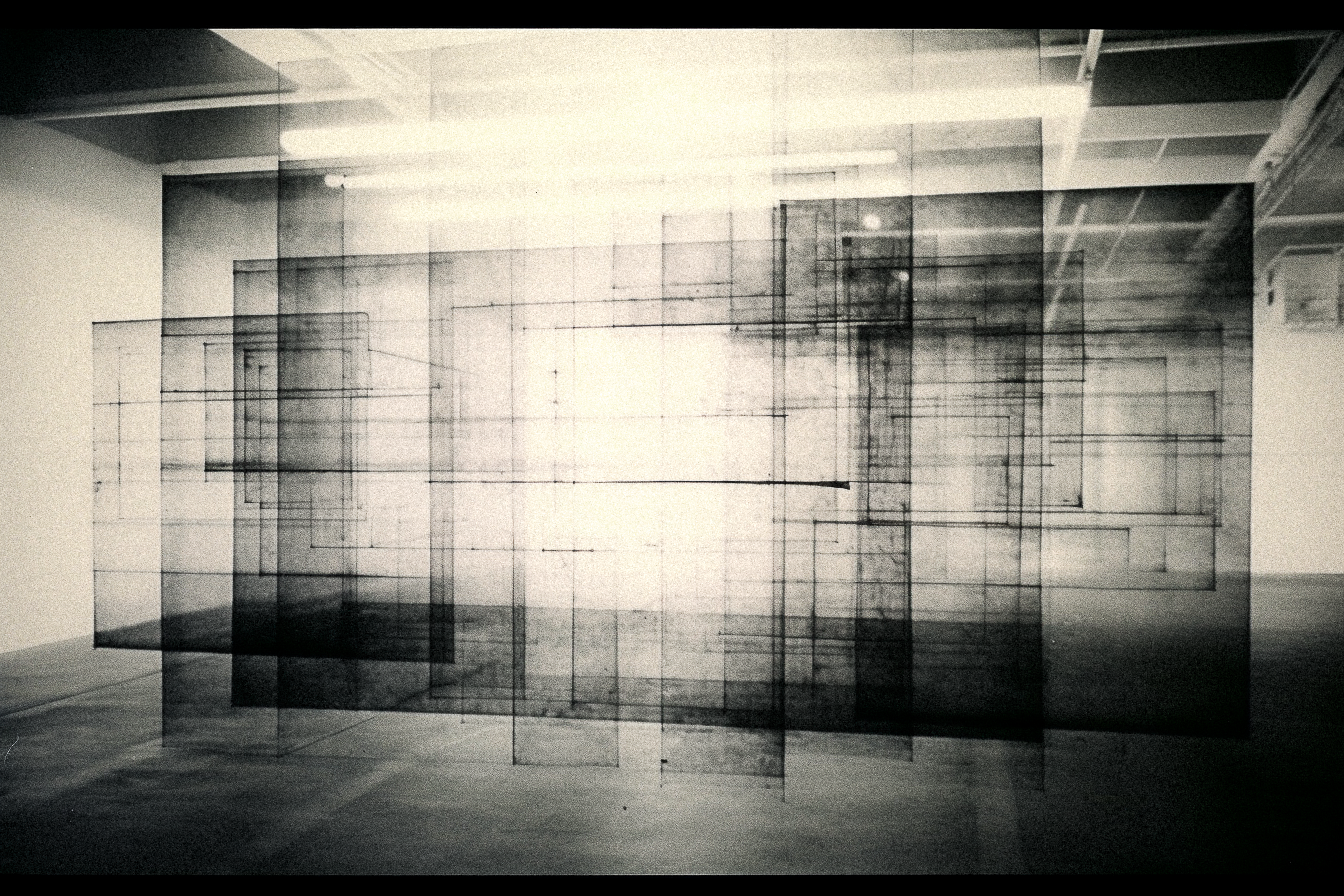

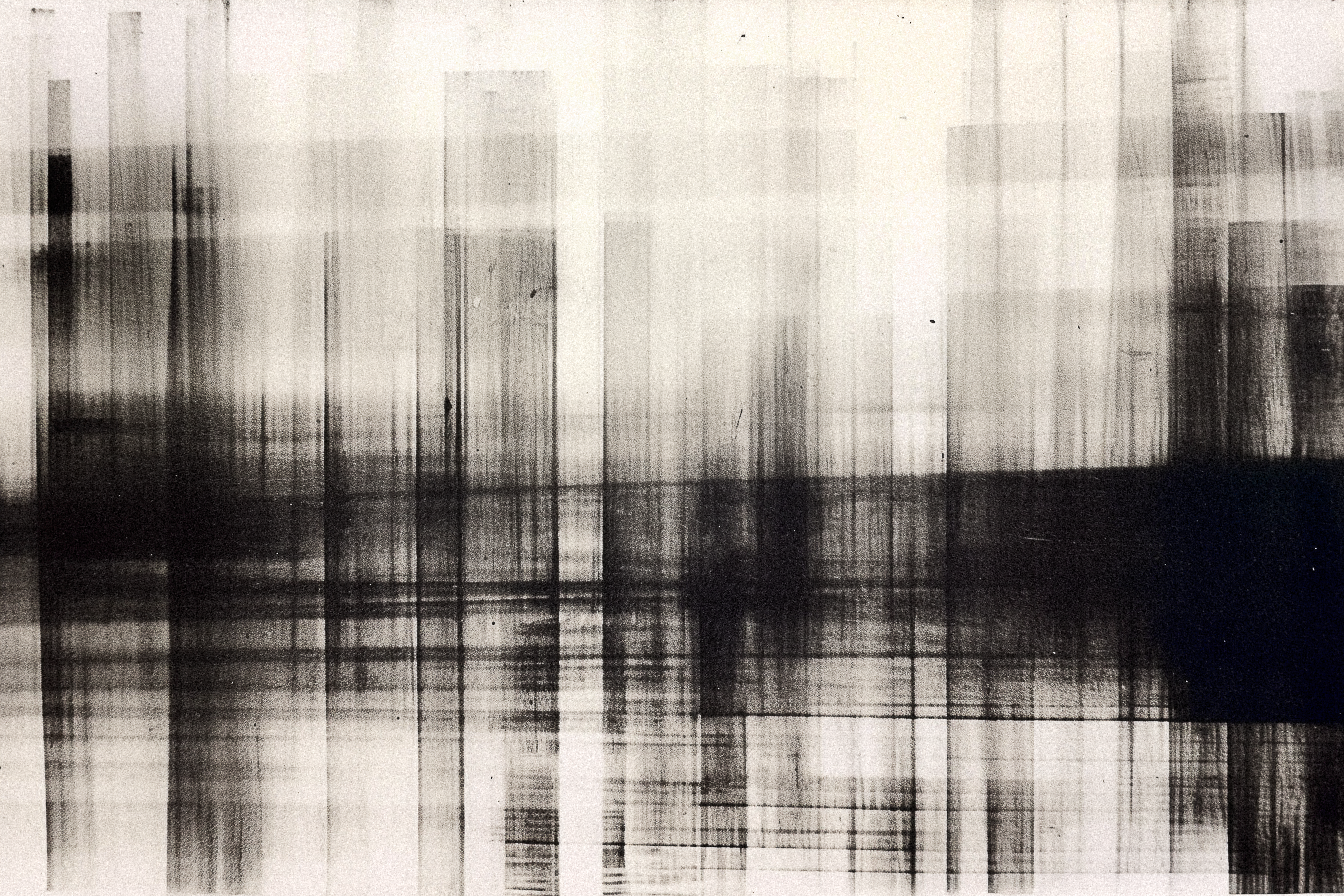

Another option might be to think of how Critical AI Art, distinguishing itself from the oversaturation of prevalent AI imagery might reflect on the profound shift in art’s interaction with technology and culture, revisiting themes central to the Pictures Generation—such as media influence and appropriation—through the lens of contemporary digital practices. By employing generative algorithms, this approach not only generates new visual forms but also engages critically with the saturation of images, probing the essence of authenticity, originality, and the evolving role of both artists and non-artists. This dynamic interaction underscores a broader, ongoing dialogue with the history of art revealing how artistic methodologies are shaped by the recursive nature of cultural and technological advancements. Here, a hauntological approach to AI Art be productive, such as the theory-fiction project I did last year, On an Art Experiment in Soviet Lithuania which reflects on the refusal of the avant-garde by the Soviet Union, the loss of Lithuania’s freedom to Soviet-Russian rule between 1945 and 1991, and art in the 1970s.

But there are other possibilities for using AI to make art. I’d like to conclude by citing one key artist from the Pictures Generation who I haven’t mentioned: David Salle. Curiously Salle is one of the only serious artists without a technology background to be publicly experimenting with AIs. Salle’s process has always been characterized by an innovative use of imagery and a negotiation back and forth between media, often starting with photographs he takes, which serve as the basis for his layered and complex paintings. Described in a lengthy New York Times article entitled “Is This Good Enough to Fool my Gallerist?” Salle’s method reflects a blend of the real and the conceptual, pushing the boundaries of narrative and abstraction in his work. Starting in 2023, Salle and a team of computer scientists worked on an iPad-based program trained on a dataset of his paintings and refined based on his input, showcasing an example of how AI can be employed to conceptualize variations of artwork, aiding in the brainstorming process for new paintings. Salle’s foray into AI art can be seen as an example of critical AI art, where the use of technology is not merely for the creation of art but serves as a commentary on the process of art-making itself. By integrating AI into his practice, Salle engages in a dialogue with the contemporary art world about originality, creativity, and the role of the artist in the digital age. Concluding the article, journalist Zachary Small lets Salle have the last word.

What will become of his own identity, as the algorithm continues to produce more Salle paintings than he could ever imagine? Some days, it seems like the algorithm is an assistant. Other days, it’s like a child.

When asked if the A.I. would replace him entirely one day, the artist shrugged.

“Well,” he said, “that’s the future.”

Can David Salle Teach A.I. How to Create Good Art? – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

A future, which is still totally reliant on the past.

One last point. As is my wont, in this essay I have focused on art from the 1960s onwards, but there are other models that might come to the fore again in this era. In particular, the Renaissance model of inspiration is an interesting one to reflect upon. Renaissance art theory was underpinned by the concept of imitatio (imitation), which was considered a noble pursuit. Imitation in the Renaissance sense involved studying and emulating the excellence of ancient art to grasp its underlying principles of beauty, proportion, and harmony. However, this process was not about mere copying; it was about surpassing the models from the past, a concept known as aemulatio. And that, very well, may be the future (of the past) in our art.