Although the final nail hasn’t been hammered into the coffin, New Jersey governor Christopher Christie has unilaterally cancelled ARC (Access to the Region’s Core), new tunnel to connect New York City to New Jersey.

Now, ARC itself is a damaged project. Instead of ending in Penn Station or having any hope of exiting in a future Moynihan Station (the plan to reconstruct the Beaux-Arts post office across the street into a 21st century version of the glorious old Penn Station that used to greet travelers prior to the 1960s). But instead, due to politics and complexities of existing infrastructure, ARC was to terminate off-site and deep underground, making arrival at Moynihan station impossible and complicating connections to other rail lines.

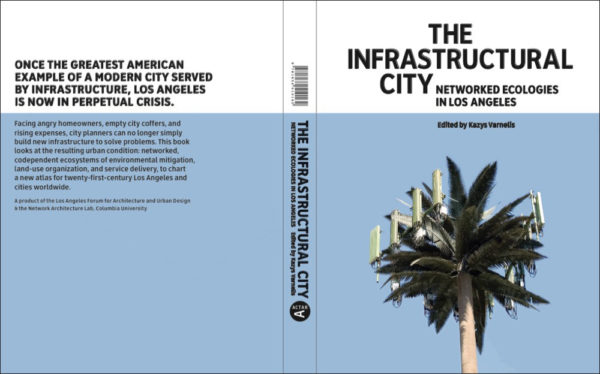

The Infrastructural City‘s lesson is that, if you give constituents and politicians enough power and you build a complex enough civilization in which notions of civil society are replaced by ideas of property rights, you are going to bring future growth to a crashing halt. So Los Angeles strangles on itself.

The creative destruction of the New York City of consensus and big projects by a succession of mayors since Ed Koch certainly helped its recover. Finance has done very well and the city has become a playground for the wealthy even as manufacturing and the middle class have been eviscerated. But for now, the city is still unsustainable without the large numbers of commuters that work in the towers throughout Manhattan. This is a dirty secret that Manhattanites—including all too many architects and urbanists—don’t want to admit. I haven’t found a comprehensive source of statistics this morning, so my figures are a little cobbled together, still, at least 900,000 commuters enter into Manhattan every day via New Jersey Transit, Long Island Rail Road, the Port Authority rail lines, and the buses that go in and out of Port Authority. In contrast, only some 628,000 workers from Manhattan work on the island (what do all the rest of the 1.2 million people do?) and some 880,000 workers from the other boroughs commute in. Now again, don’t rely on these figures too much, but still they seem to be roughly on target in suggesting that the majority of community into the city comes from the suburbs.

But infrastructure in and out to the suburbs is at a breaking point. Amtrak has been starved of funds for decades and its tracks and tunnels are in a horrific state of disrepair. Since New Jersey Transit has to share the Amtrak train lines in and out of the city, it has to face congestion caused by constant technical glitches on the aged, overstressed Amtrak lines. But since Amtrak owns the lines, it gets priority when only one of two tunnels is running in and out of the city.

Now Christie’s constituency is residents who don’t commute to New York. On paper, his motivation is the opportunity to use ARC funding for highway repairs. Still, he’s a Republican and when they’re involved its hard not to imagine conspiracy theories. In particular, its plausible that part of the economic mess the country is in is due to the "Starve the Beast" policies of a generation of conservatives. Using profligate tax cuts, stave the beast was meant to create fiscal conditions that would force massive cuts in government services. The impossible situation that we face today is arguably the result. No matter how utterly incompetent the Obama administration has been, there is little question that their hands have been tied by the massive deficit and debt incurred by the Bush administration. If one applied this sort of reasoning to Christie’s move, its plausible to imagine that it’s an anti-city project, aimed to make commuting in and out of the city so much more difficult, thus forcing workers and—more importantly—corporations to either move into the city (unlikely, given current demographic flows) or to move further out into exurban areas. These, in turn, have historically been more conservative in nature (this has a bit to do with the lack of shared infrastructure, roads aside, and the insulation that exurbanites feel from the poor). So, in other words, canceling ARC is a foresighted move that will likely make it impossible for Christie to get re-elected (given the money and votes concentrated in the commuting suburbs) but will make it possible for a shift further rightward in state politics over the next several decades and, in turn, help undermine Manhattan’s future.